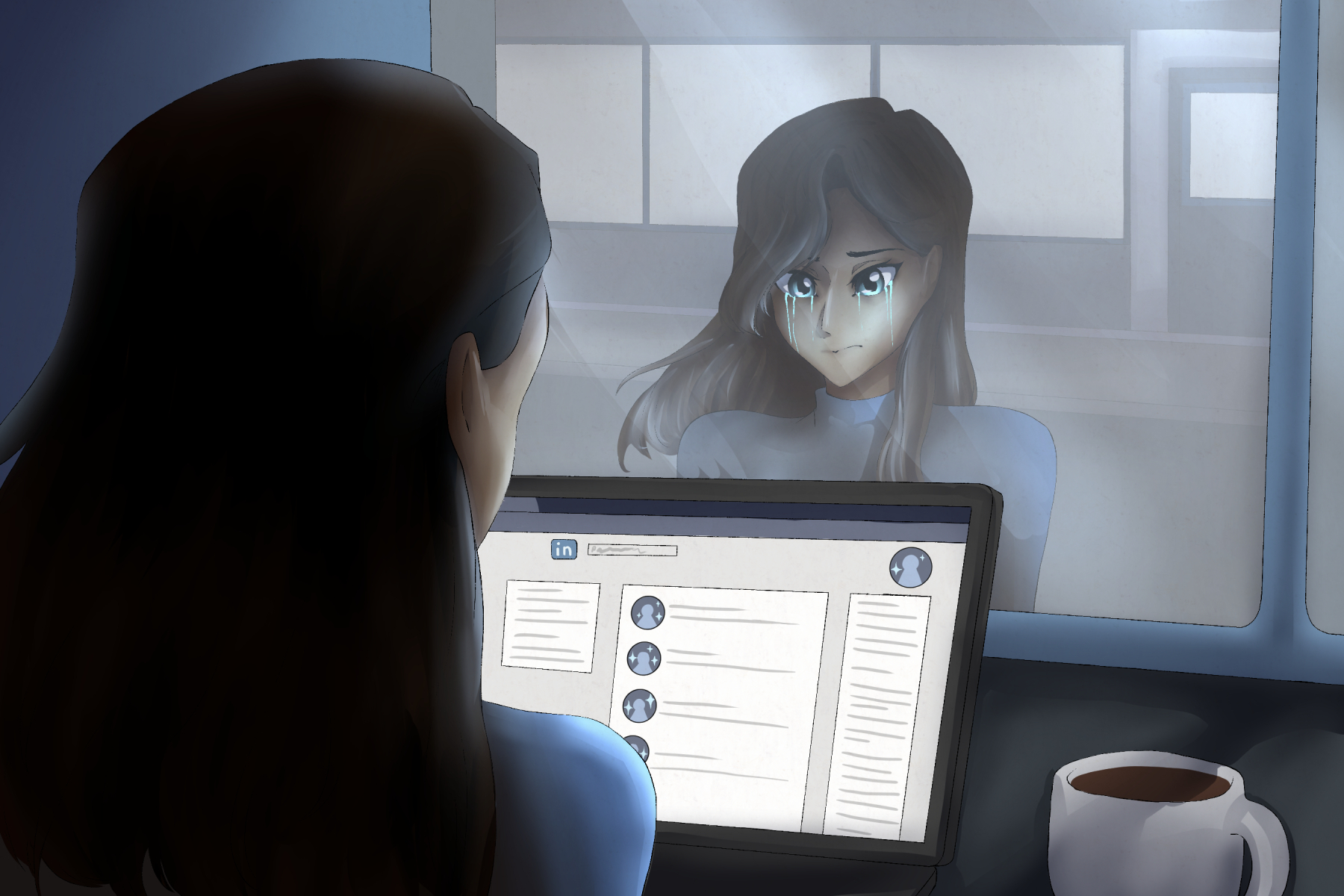

Social media is a double-edged sword of self-validation and comparison. On one hand, users carefully cultivate an idealized online version of themselves to receive a dopamine rush from every interaction with one of their posts. On the contrary, it enables self-comparison and envy of a stranger’s seemingly perfect life. Social media is more than just one’s online persona; like society, it harbors unsaid rules and societal etiquette that determines an individual’s popularity and community inclusion.

Instagram, Facebook and Snapchat are popular social media platforms with such double-edged effects. LinkedIn, a social media platform for networking and job employment, is arguably one of the most toxic forms of social media.

Founded in 2002 by Reid Hoffman, LinkedIn’s mission statement is to “connect the world’s professionals to make them more productive and successful.” Users can upload their resumes and other relevant information, apply for jobs and connect with others. Like other social media platforms, users can post photos, videos, events and articles, as well as like, comment on and follow other accounts. According to their website, LinkedIn hosts “900 million members in more than 200 countries and territories worldwide.”

Like social media, LinkedIn has its benefits: it is the largest professional networking website, thus it is a vast and reliable source for those looking for employment and networking opportunities. The platform features an “endorsements” section where individuals can build credibility by receiving endorsements from other users. Most importantly, LinkedIn is widely accessible: it is free to create an account (although it also offers paid premium membership options).

LinkedIn’s downfalls, however, are just as plentiful as its benefits: the constant pressure of comparison, the quantity of achievements, humble bragging and toxic positivity. LinkedIn users can view the number of connections, followers and likes on other people’s profiles. Such numbers become an indicator of whether a user is well-liked or popular enough. In 2021, Instagram chose to allow accounts to hide their number of likes on posts to eliminate comparison and the pressures of posting. Instagram tweeted: “We want your friends to focus on the photos and videos you share, not how many likes they get.” In an interview with Wired, the CEO of Instagram, Adam Mosseri, explained that hiding likes was an attempt to “depressurize Instagram, make it less of a competition.”

This was one way to prevent comparison and competition within social media, which LinkedIn has not tried to circumvent. Rather, users are able to view not only each other’s posts, but the posts their mutual connections like and comment upon. This creates a culture of surveillance that pressures users to portray an inflated sense of positivity. As employers can view prospective employees’ likes and comments on posts, users carefully choose which posts and perspectives they support. Hence, job-seekers will curate their likes and comments in an attempt to seem like ideal job candidates.

This pressure to appear perfect enables shallowness and toxic positivity, defined as “the pressure to only display positive emotions, suppressing any negative emotions, feelings, reactions, or experiences” by BetterUp. LinkedIn is also a platform that promotes professionalism. No individual wants to be perceived as flawed by employers; therefore, users cultivate a carefully curated and overwhelmingly positive persona devoid of real personality.

Furthermore, LinkedIn is primarily used for “humble bragging.” Users only display and promote their best qualities and accomplishments. Often the platform’s posts have the same formulaic caption: “I am beyond excited/happy to share/announce that I have accepted an offer to join (*insert company*) as a (*insert position*). I want to thank everyone who has guided/supported me/I can’t wait to start this new chapter!” Rarely does anyone complain or post about weaknesses or moments of vulnerability. It is the etiquette on LinkedIn to highlight the quantity of one’s internships and experiences rather than one’s holistic character and skills. Moreover, the platform allows users to fully view someone’s entire LinkedIn page and resume, which inevitably causes comparison and envy.

Statistical insights like “# number of people have viewed your profile” and “# number of people searched for you” are also provided by LinkedIn. This quantifiable data reinforces the importance of being perceived as successful and accomplished. When given this information (e.g. ‘top companies your searchers work at’ and ‘top job titles of your searches’) but not the specific identities of your searchers/viewers, LinkedIn capitalizes on the user’s curiosity, urging them to buy into LinkedIn’s paid premium memberships.

Unlike social media apps like Instagram or Facebook, you cannot step away or delete LinkedIn — it is the livelihood and the future of one’s career. Despite this, it is up to users to transform LinkedIn from a space primarily of comparison, toxic positivity and shallowness to one that highlights human connection. For example, given the recent large-scale Google layoffs publicized on LinkedIn, current and laid-off employees reached out and connected with one another to provide opportunities, referrals and help to those affected. Social media reflects the society it represents: good people can do good things, and it is up to the people themselves to change systems.