Anyone who has experienced the loss of a loved one understands the strange journey that is the grieving process. While you’re trying to comprehend the fact that a large presence in your life is now missing, you also have to deal with being treated like glass anytime you leave the house. People are unsure how to talk to you.

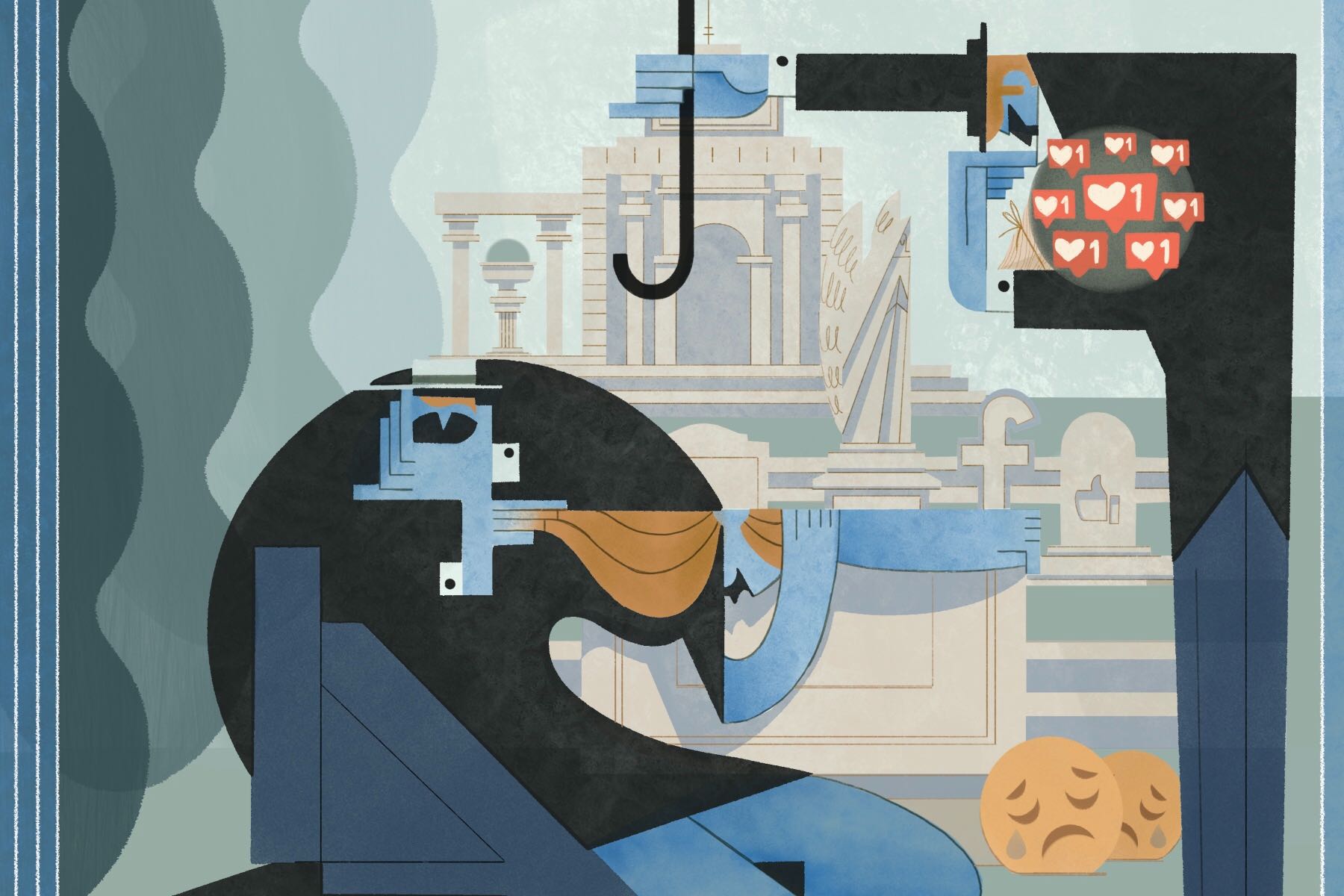

There are 15 unread texts on your phone filled with strings of different colored heart emojis. You’re being pulled in for shaky hugs whenever others get the chance. In general, people mean well, but are extremely uncomfortable with comforting you face to face. That’s when they find solace in the safety net that is social media.

You’re able to know everything about everyone, while also keeping a safe distance from them. You’re close, but not too close. People can offer their dearest sympathies to the bereaved without having to see their eyes gloss over, or the pain dance its way across their face. It seems like the perfect solution, except, not entirely. Social media has little merit for most of those who are grieving.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-NqHwDBiL4/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

The internet is special in the sense that it has made every average person into a D-list celebrity. No one is particularly special, and the paparazzi isn’t busting down your door, but if something happens, rest assured that your followers and all their friends will know about it. There are times when this is good, like when you get that new job or when you get married. Then, there are times when this is not so good, like when you lose someone close to you.

Many may think that the only way users can know anything about their life is if they themselves post it, but that’s not necessarily true — the eighth wonder of the world is how people online find out things you never told them.

Claire Wilmot discussed her own sister’s death in The Atlantic, touching on how quickly information can travel: “Lauren’s death had torn a hole in my universe, and I knew the moment I moved I would fall right through it. Meanwhile, across the city, a former classmate of Lauren’s learned of her death. I’m still not sure how — she hadn’t kept in touch with Lauren during the three years since they graduated high school. But bad news travels astonishingly fast.”

An experience like Wilmot’s appears to be common in this day and age. A decade or two ago, grieving could be done in private, but today, when someone passes away, everyone will know. There’s a certain horror to this. Those in mourning are on their own reality TV show.

Everyone has their eyes on them and everyone wants to keep up with the drama, but no one actually wants to be there to pick up the crumbling pieces. It’s almost like being kept in a display case. People will pass by and ogle for a few seconds, but that’s pretty much as far as they’ll go.

While social media is a great way to communicate, it’s also a great way to isolate. Those grieving will receive no shortage of sugary sweet condolences and comments about heaven gaining an angel, but screens can become walls. Unfortunately, it’s incredibly easy to lose your empathy in an online space, where you cannot see the person you are talking to.

When a small part of your brain has trouble recognizing that they are in fact a real person with real feelings, it’s obvious to whoever’s on the receiving end. There’s an emptiness behind the words people type; they’re too far removed from the actual horror that they make the receiver feel more alone than they already do. The internet is not the great outlet for public grieving that it thinks it is.

It adds to the messy reality of loss. It dilutes the severity of the tragedy. Because of the fast-paced nature of social media, the world is desensitized to misery. Users have access to a constant stream of information, and today’s big story will be forgotten tomorrow. Hardly anything is shocking anymore. News of deaths are read in between ads for the newest mobile game and cute cat videos.

It’s astonishing that some feel they’ve done their civic duty after just dropping a quick “RIP” and a prayer hands emoji, as if something that took two seconds to type could heal what is going to become a lifetime tear in the heart.

Of course, grieving is complicated for everyone, whether you’re the one doing it or the one watching someone do it. It’s hard to comfort someone who is trying to comprehend the incomprehensible.

It’s true that rosy comments with nothing beneath the surface can be offensive, but it’s human nature to want to make sense of everything, to want neat and tidy endings. While there should certainly be a stronger sense of understanding involved, people cannot be entirely faulted for the way they react to tragedies.

Social media can also have its little plus sides when it comes to remembering loved ones. On Facebook, you can set up memorialized accounts where photos and happy memories of the deceased can be shared among family and friends. Additionally, many feel as though they can still reach their loved ones by keeping their profiles up and scrolling through old posts.

This digital age has changed what it means to mourn the loss of a loved one. While social media is a way for a community to come together in hopes that no one feels isolated, it can do more harm than good. There’s a lot of work to be done. The distance provided by the internet doesn’t necessarily make sympathies less meaningful; it’s the actions taken that do.

There isn’t yet an established virtual etiquette on how to treat the bereaved, and there may never be, since grief is an indescribable emotion, but there definitely needs to be more compassion. The key here is empathy. Taking a moment to stop and think about what others may be experiencing and moving forward with that notion in mind can change a situation entirely, and help others in feeling not so alone.