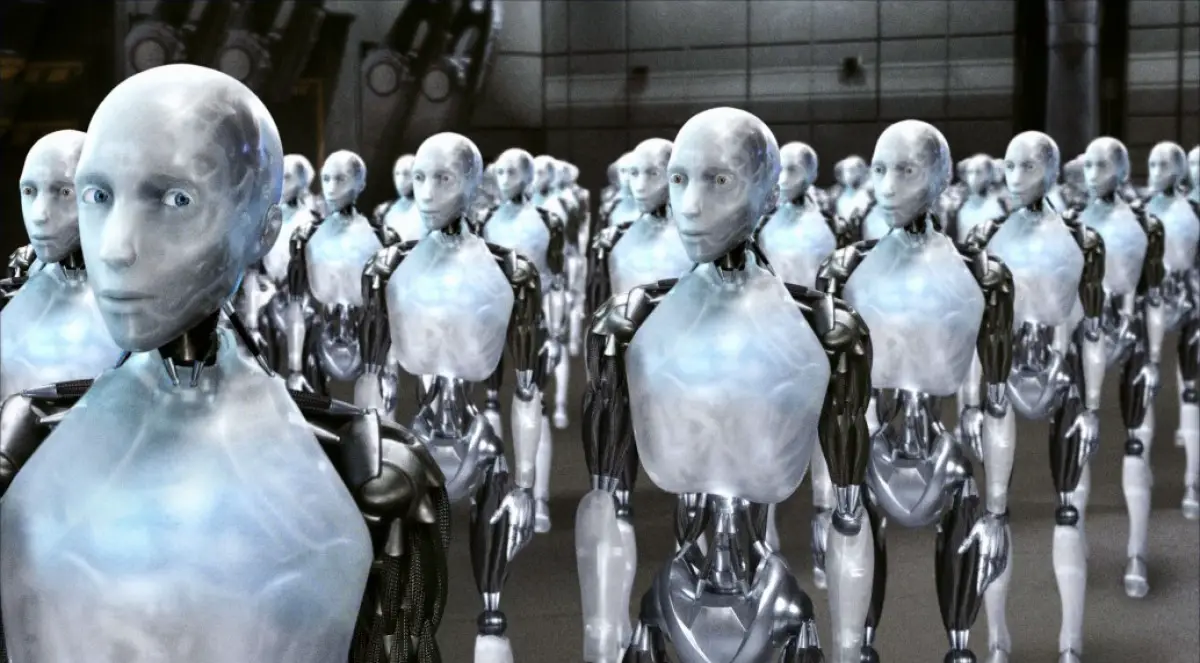

The year is 2038. Human-like androids are mass produced by a company called CyberLife. The androids are programmed to obey their humans without question — no matter the order.

This may sound cruel, but it’s completely ethical, since androids aren’t sentient and they don’t feel empathy — right? This is the premise behind Paris-based game company Quantic Dream’s newest PlayStation 4 exclusive, “Detroit: Become Human.” After years of fans eagerly awaiting the game after the release of the 2012 “Kara” tech demo, the narrative adventure finally came out last month.

Consistent with other Quantic Dream games, “Detroit: Become Human” is essentially an interactive movie, which makes it great for non-gamers to seamlessly pick up. Players take on the roles of three androids: Kara, a housekeeping android who forms an attachment with Alice, a traumatized little girl; Markus, who goes from being a caretaker for an elderly man to the leader of the android rebellion; and Connor, the first android police investigator who works with a cantankerous alcoholic lieutenant in order to solve a series of crimes committed by deviants.

Deviants are androids who have broken out of their programming and become sentient — if you’ve watched or read “I, Robot,” you probably have some idea of where this is going.

Utilizing their standard storytelling methods, Quantic Dream’s poignant story is told mostly through mundane activities, such as putting dishes away or playing a piano. These are activities that players can relate to in their everyday lives, and as a result, help immerse them in the characters’ world — the amazing motion-capture graphics certainly help as well.

One reason “Detroit: Become Human” succeeds is by seamlessly integrating the mechanics and narrative. Players are able to pause the game in order to look around for highlighted items or evaluate potential actions. If the character were human the gamer would likely be taken out of the immersive experience, but it feels perfectly natural as an android.

These android “superpowers” are taken even further with Connor, as you are able to piece together events at a crime scene and, strangely enough, determine a human or android’s identity by placing their blood in your mouth to analyze.

Another area “Detroit” shines in is the sheer breadth of content. Many choice-based games don’t feature decisions that meaningfully alter the narrative (ahem, Telltale Games who notably made “The Walking Dead” video game series), yet “Detroit” features choice branches that culminate in seven different endings, which results in around 40 hours of gameplay in order to discover all the content. Additionally, each of the three protagonists can die on multiple occasions, depending on the player’s choices.

After each individual scene, players can review a flowchart to see what branches they have yet to experience, as well as how their choices stack up against other players. One of the most powerful decisions (with a strong payoff) is whether you choose to lead a violent rebellion, or turn the other cheek and take the path of pacifism.

While players ultimately make these decisions, the choices made and paths taken shouldn’t be taken lightly, as the characters are endearing and empathetic. When playing as Connor, you work alongside lieutenant Hank, who isn’t a fan of you, let alone androids in general. During my play through, I felt frustrated when I tried several tactics to appeal to Hank, yet he wasn’t responding. I desperately wanted to connect with him.

I could discuss narrative branching and characters all day, but the most striking aspect of “Detroit” is its incredibly controversial subject matter.

Quantic Dream writer and director David Cage is no stranger to controversy. Not only has he recently been accused of fostering a toxic work environment and turning a blind eye to racism and sexism (which he vehemently denies), but he’s also been accused of victimizing digital women.

Three of Cage’s games — “Heavy Rain”, “Beyond: Two Souls” and now “Detroit: Become Human” — contain scenes in which a female character is reduced to a damsel in distress. While this doesn’t bode well for Cage’s treatment of women, at least in “Detroit,” Kara gets herself out of the situation and doesn’t have to rely on a man to save her. In fact, she helps to free a tall male android named Luther who then looks to her for guidance.

Another common criticism of the game is that it not only trivializes racism, but fails to own the anti-racist sentiment. In “Detroit,” androids can only ride in the back of the bus, are considered property of their owners and have no rights. As rebellion leader Markus, players can choose to tag a building with “I have a dream.” The comparison to slavery and the civil rights movement is achingly obvious, yet Cage refuses to acknowledge the motif. He emphasized his newest game is about androids who want to be free, and his intent wasn’t to send a message or draw heavily from real world history.

Throughout most of the game, the historical comparisons are mostly allusions, until near the end when a woman said she will help smuggle Kara the android across the border, and then directly compared the android situation to the long history of oppression toward black people. I found it odd that up until then, no other characters had mentioned the obvious.

Oddly enough, race is ignored all together in “Detroit: Become Human,” despite featuring characters of color. Markus is seemingly a light-skinned black android, yet it is never mentioned. Although the apparent intention is to prioritize the conflict between man and machine over race wars, it’s important to recognize race.

Another controversial issue the game takes on is domestic abuse, although this time the sensitive subject is handled quite effectively. The violence isn’t glorified or used solely to further the plot, while the abuser is portrayed as a depraved person. The player, as Kara, is encouraged to take action.

When game developers tackle serious topics, they’re playing a dangerous game, but one that will pay off if done effectively, especially when issues are relevant in today’s society. Games that strive to engage players’ moral and ethical frameworks can open up a meaningful dialogue about such issues and encourage action-taking.

Despite the fact that the subject matter could have been handled differently, the game does succeed in not only evoking empathy, but rewarding the player for doing so as they experience becoming human.