“The Bleeding Edge” lifts the veil. It’s an intense drama detailing the struggles of patients who have been harmed by medical devices, but it also exposes the real culprit of their pain: corruption in the FDA and corporate greed.

The most extensive coverage included in the film is of Essure, a permanent birth control method that caused an uproar around the world. Essure, a small metal implant, was designed to be inserted into the fallopian tubes and agitate their lining. This would then cause scarring around the implant and serve just as tubal ligation would.

It’s a great concept, but many women’s bodies rejected the implant, sending it to their uterus. Others bled excessively, one of whom is featured in the film and says when she reported this to her doctor, he suggested her bleeding was because she was Latina.

When surgeons attempted to remove the implants, they often broke, spreading fragments and leading to even more removal surgeries. As appalling as this is, and as much as it might make “The Bleeding Edge” seem like a fearmongering anti-birth control movie, such stories are just part of a much larger picture.

The background of that picture, if you will, is an FDA-approval process called the 510(k). It was passed originally as a revision to the FDA’s primary approval process, which required clinical trials, but has now become the norm by which 98 percent of devices are introduced to the market.

Under the 510(k), the only requirement is that a product must be “substantially equivalent” to one that has been approved in the past. This means products can be approved based on the approval of other products that are themselves only approved on the clearing of even older products.

What’s more, even if a device that is used to grant the approval of others is recalled, the others can legally remain on the market. With the exception of Essure, all of the devices featured in the film were approved through the 510(k).

Overuse of the 510(k) explains why often the first people to discover side effects are patients. Not only are they left to discover them, but they also carry the burden of reporting them.

Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, a professor of pharmacology and physiology at Georgetown University, appears on “The Bleeding Edge” with a study that found the worse the outcomes are, the less likely they are to be reported. Only an estimated 3 – 4 percent of total complications following device implants are reported at all, mainly because the system relies on self-reporting.

“The Bleeding Edge” represents beating the odds, and is mostly told by patients who did much more than self-report their symptoms. Months after having a cobalt hip replacement, one patient, who is ironically a doctor also, linked his intensifying mental hiccups to his recent surgery.

Parts of the cobalt had dissolved into his bloodstream and begun to poison him. Using his own medical expertise, he conducted studies using data from other cobalt joint replacement patients who shared symptoms, and he now lectures on his results across the country.

The movement against Essure began as just a Facebook group, “Essure Problems,” where women connected over similar experiences. Eventually, the group became an organization and movement with over 40,000 members worldwide. Their pressure on the EU led Bayer to take Essure off the market in Europe.

In the early stages of the group’s development, they pooled money to obtain a video of the FDA-approval meeting where researchers presented their clinical trials. The video is included in the documentary, showing questions being glossed over – questions like “What happens if the patient is allergic to the metal in the implant?”

A lead investigator is also shown on video saying he “received compensation,” which “represented a financial interest in the company.” Even though the film may seem overly dramatic in parts — mainly because of the music — the evidence for negligence and conflict of interest is impartial and honest, and is often shown through a primary source, like the footage from the FDA meeting.

It also seems to focus too much on Essure and not enough on some of the other medical devices. There’s a trade-off though: weeks before the documentary was released, Bayer announced it would take Essure off the market in the U.S. by December. Had the directors covered other stories more, it might have had less of an impact on Bayer.

The movement against Essure appears to be the only backbone of the film. However, without the substance of that movement — the history, the size of it, the progress — there might not have been a platform to give the other stories with less substance. Some of the most shocking parts of the film lasted only five or six minutes.

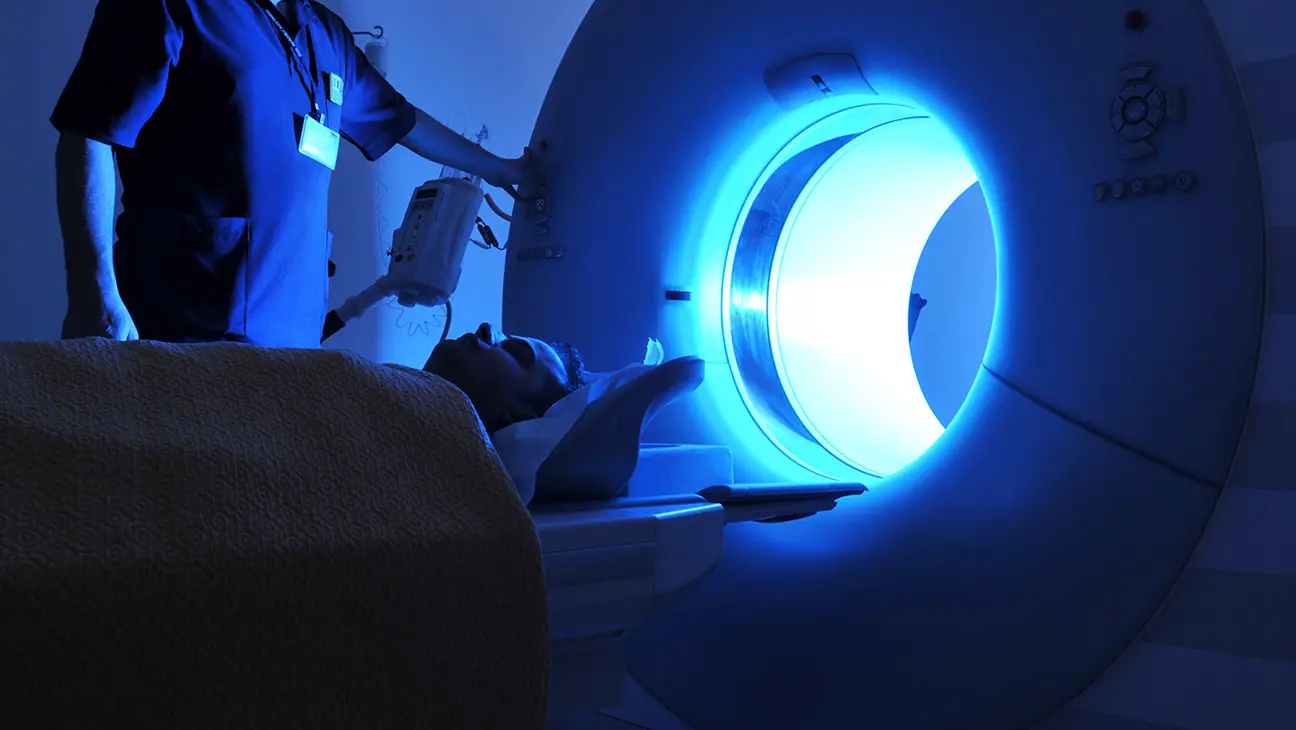

A great example of this is the brief section on the CT scanner. Dr. Julian Nicholas, a scientist at the FDA from 2006 – 2009, received an application for its approval. He knew that overuse of the scanner could cause cancer, so he and nine other scientists proposed a warning label be required to be placed on the machine before it could be sold to hospitals.

They received massive pushback and the scientists were “fired or let go” within two years of trying to push through their proposal. Also, a U.S. Congress joint staff report in 2014 found that Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, the director of the FDA at that time, had installed Spector software on the whistleblowers’ computers.

Another example has to do with the da Vinci robot. Made by Intuitive Surgical, the da Vinci is designed to perform minimally invasive surgeries. Its controller measures the surgeon’s hand movements with sophistication, and it’s recommended for operations like hysterectomies. The problem with it is training.

When the da Vinci robot was submitted to the FDA to be approved, Intuitive Surgical required hospitals sign surgeons up for nine weeks of training along with their purchase of the system. Weeks before its clearance, they dropped that requirement. A current da Vinci cardiac surgeon appears on the film saying he “didn’t really start to feel comfortable until about 200 or 300 cases in,” and that he was told he would need about 10 cases to become “good.”

What type of surgery he’s talking about exactly is unknown, and he might just be a slow learner, but the complications related to da Vinci surgeries could be prevented if training was standardized. As of now, it varies from hospital to hospital.

These issues may seem far away or overshadowed by the other domestic health problems like the opioid crisis or conspiracies against “big pharma.” When I first watched the film, it seemed overly dramatic as well, but the facts stood out. I shared it with my family and realized corruption in the medical device industry isn’t far from my life at all, even though I thought it was.

Apparently, my cousin who worked at a law firm had a number of cases related to the Prolift, one of the implants featured in “The Bleeding Edge.” The Prolift, made by Johnson and Johnson’s company Ethicon, is a pelvic mesh made from material previously used to close hernias. It is designed to assist deteriorated tissue around women’s reproductive organs.

While it can be supportive, it can cause scar tissue buildup and become fixed in problematic positions for women, making it hard to walk comfortably and without pain. Removal also leads to surgery after surgery — I personally know someone who had to endure over five of these surgeries, managing to only get pieces out each time. Her recoveries were brutal.

The last example is simple but telling: The surgeon who performed my mom’s partial knee replacement was part of the team of scientists who designed the replacement part itself. Within a year of the surgery, doctors confirmed that the problem with my mom’s knee was no longer mechanical — over seven surgeries throughout the last two decades had apparently taken care of that.

They said the pain was related to her nervous system, and that the knee replacement was not going to help as they expected. It seemed like their diagnosis suddenly became more accurate after the surgery was paid for.

One day most of us will be patients. We can all benefit from the innovations of the medical device industry, and we can all be harmed by negligence in their testing stages. The change the world will need in the future is risky and should stretch the boundaries of what’s safe, but we need to make sure people are informed of the risks.