According to Section 175 of the U.S. flag code, “No person shall display… any other national or international flag equal, above, or in a position of superior prominence or honor to, or in place of, the flag of the United States at any place within the United States.” On August 20, a small town’s football team didn’t just break the law — it became a source of pride. The Monarch Quarterback Club in Marysville, Ohio published a promotional photo to their website featuring senior players holding various icons, from the thin blue line flag to the school’s emblem. The U.S. flag is in the lower left-hand corner, below two more of its desecrations.

Such a strange image shouldn’t be too surprising for those who call it home. Marysville is located just northwest of Columbus, the state capital. It’s a hyper-conservative village of 24,000 people whose politicians, however liberal, try their darnedest to appeal to the Republican base. And nothing brings out the heart of the community like good ‘ol Friday night football. If only its arteries weren’t clogged.

“As most football teams are in midwestern towns, the MHS football team is a direct representation and reflection of Marysville Exempted Village School District,” explained my friend Sarah, who graduated from Marysville High School a year before I did.

Not only that, but given the sport’s salience to the community at large (the city recently spent over $10 million on a new stadium, even as its historic uptown is a crumbling disaster), any statement from the football team reveals a lot about which views are supported by the local citizenry.

Shortly after seeing the photo, Sarah denounced it on Facebook, writing that she had “never been more disgusted or ashamed to be a graduate of Marysville High School.” Although her post garnered some support from community members, Sarah became the subject of unprecedented backlash, from sexist pro-Trump memes to straight-up death threats. As a spectator to the madness, I found it gut-wrenching and deeply disheartening. “My hometown is better than this,” I thought to myself.

Hours later, I created a petition to the superintendent, asking her to address the photo and its inherent racism. Although it gathered over a thousand signatures, a counter-petition made to support the team was formed and quickly surpassed the original’s signatories by two-fold.

A rally to honor the football players was hastily scheduled some weeks in advance. ABC 6, a local news station picked the story up twice, each time deeply discounting the argument against the thin blue line flag.

When the majority of Marysville’s population looks at the photo, all they see is patriotism. Do blue lives matter? Of course they do, the police sacrifice so much! Thin green line? Well, that’s the military, isn’t it? I love the military; my family has served! And duh, the thin green line is firefighters! Who doesn’t want a good firefighter? Not once do they consider that these flags are not officially associated with the institutions they revere.

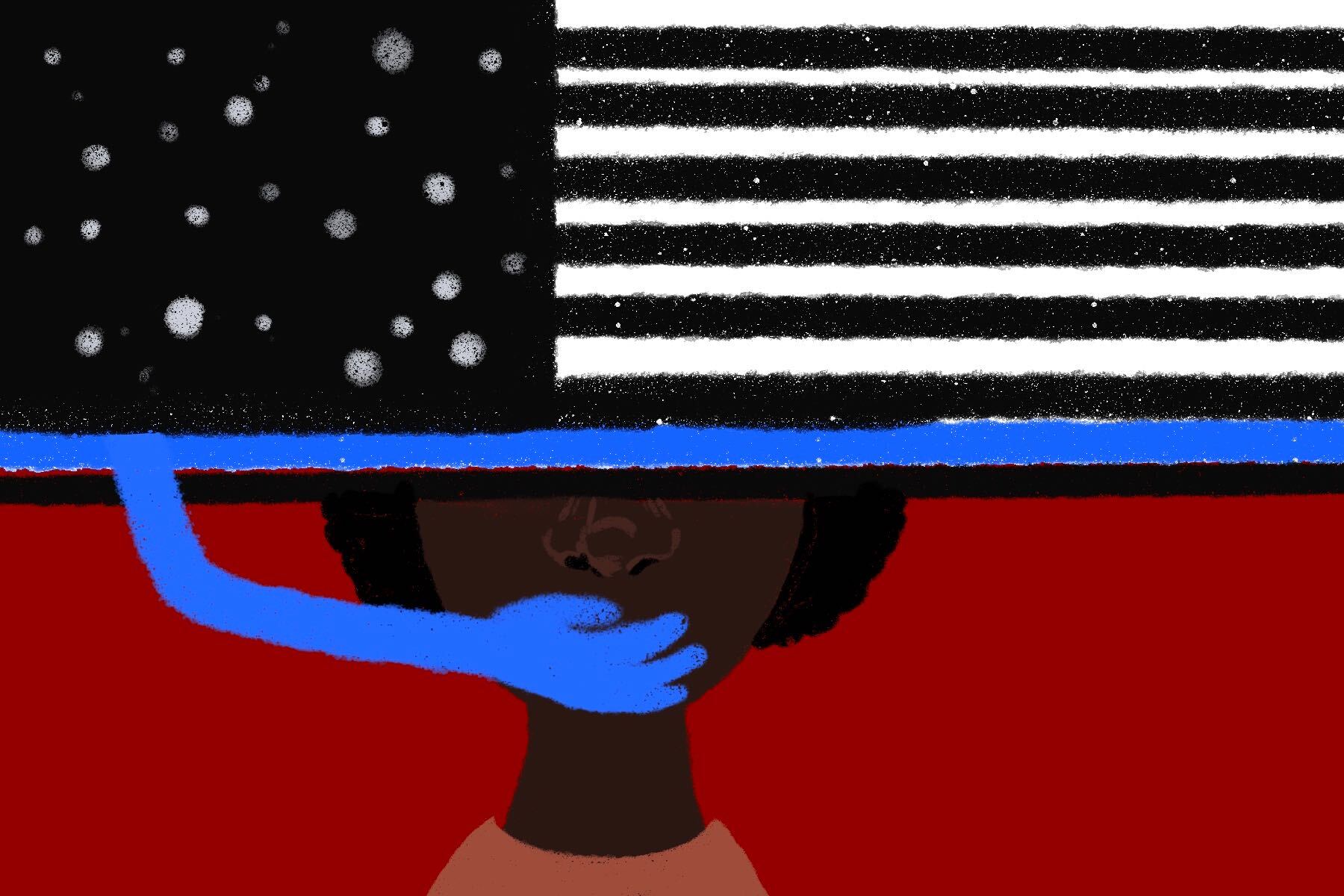

Instead, they are fringe symbols quickly creeping into the mainstream. We see it flying next to the American flag. We see it outside police stations. We see it on balloons, shoes, bracelets and bumper stickers. But where did it come from and what does it mean exactly?

The popularization of this and other desecrated flags can be traced to Thin Blue Line USA, a retailer selling all kinds of warped American symbolism. “Nearly two years ago,” a 2017 article on their website begins, “when the national support of law enforcement was needed the most, Andrew Jacob, President of Thin Blue Line USA, began a national movement.” The final word is a bit of a misnomer; the company actually began a countermovement.

When one searches “blue lives matter” on Google, the thin blue line flag is the first image to appear. As most people know at this point, Black Lives Matter was founded in 2013 in response to the acquittal of the neighborhood watchman who killed Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Floridian. The similarity of their names is far from homage. Blue lives matter is another point of view at best and hateful opposition at worst.

In 2017, the flag was flown during a neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where a counter-protester was hit by a car and killed. Just last month, 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse, whose Facebook photo featured the thin blue line flag, crossed state borders with an AR-15 and killed two protestors in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Unlike a symbol that is officially commissioned by a governmental organization, especially one that has an established reputation for representing a certain body or affiliation, any icon that a corporation designs without direct involvement from an outside or objectifying party will unfortunately only be legitimized based on how it is received across history. The thin blue line flag is quickly gathering a history of hate.

Regardless of how one sees it, the thin blue line flag should never be used by a school organization for promotional or yearbook photos. All of those pictures, never mind if they are “official” as one news station claimed they were not, are reflections of what the district approves or disapproves. From the looks of it, Marysville High School thinks blue lives exist. Of course, this case is not without precedent; there are many previous instances of speech being restricted when a school was involved.

An article published in the University of Chicago Law Review draws a distinction between pure student speech and school-sponsored speech. The first refers to the expression “that may take place anywhere yet happens to occur on school premises.” One notable example is the Supreme Court case Tinker v Des Moines, in which three students were expelled for wearing armbands against the Vietnam War to school. The Court decided that suspension was unconstitutional because it violated the students’ individual rights to free speech. Those same rules do not always apply when the school is directly connected.

While the precise definition is a bit fuzzy, school-sponsored speech involves expression that is commissioned or supported by the school in some way. In Hazelwood School District v Kuhlmeier, the Supreme Court “upheld a principal’s decision to excise student articles written for the school newspaper,” the Law Review article explains. “Speech that bears the imprimatur of the school resembles official speech, leaving the school free to employ reasonable measures to guard against misattribution.” If a promotional photograph of a school-sanctioned sports team doesn’t scream imprimatur, I am not sure what does.

All of this is to say that the use of the thin blue line flag conjures some serious legal questions about the relationship between a school district and the promotion of its organizations. At the very least, one should consider how a symbol has been used previously before trying to support a narrow understanding of its meaning. Images can enable prejudice just as easily as a person can. What happened in Marysville should be a lesson to the rest of the country that the symbols we use in public reflect not just what we think of them, but what the hateful see as well.