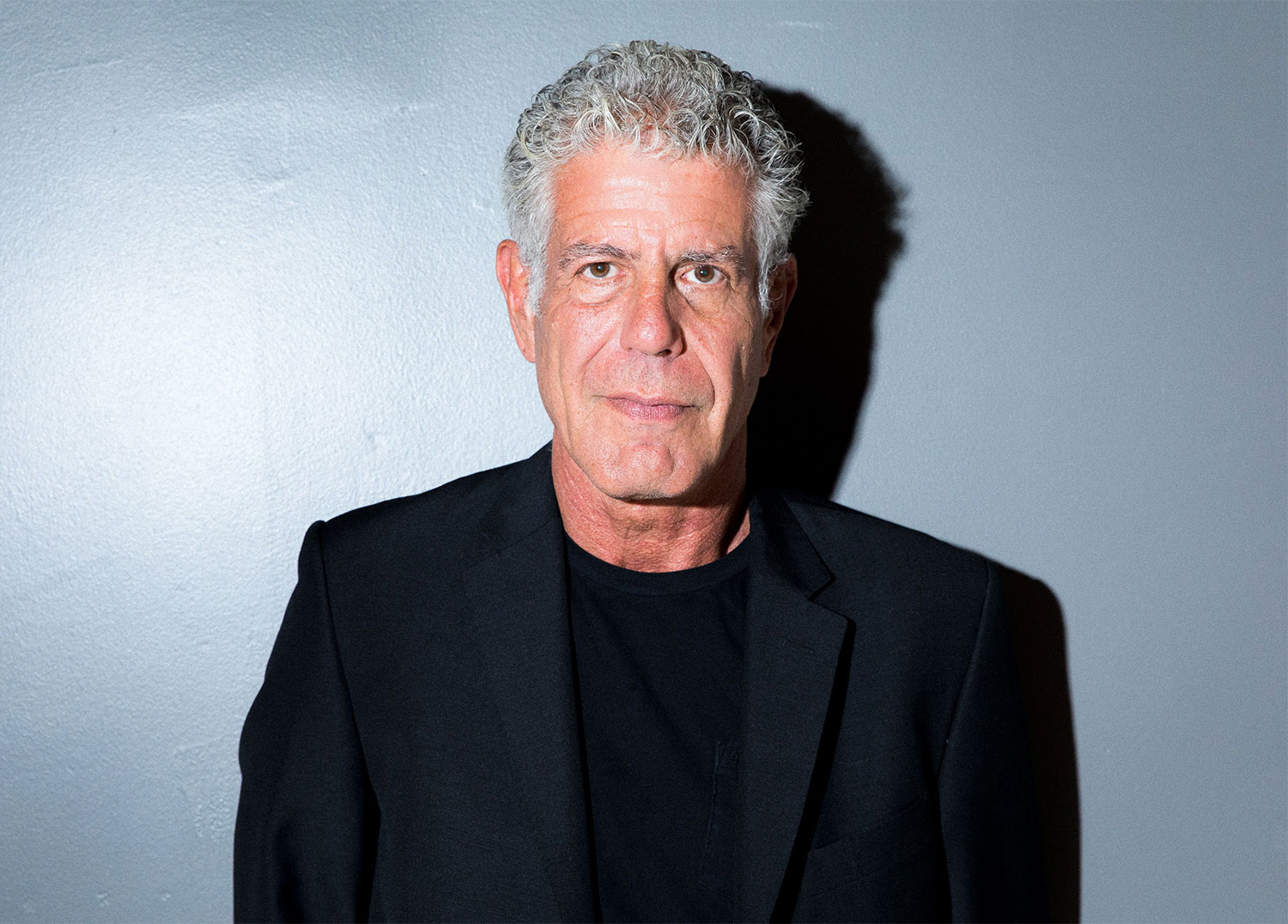

After the recent suicides of beloved celebrities Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain, discussion and concern regarding mental health surged in the United States. The push to make mental health care systems a priority is undeniably positive and badly needed, but not all conversations about mental health and suicide awareness are wholly beneficial.

There are two main problems with the usual dialogue about suicide awareness: either the discourse lacks true awareness and can result in some being harmed, or the discourse feeds into people’s personal doubts about suicide and can be just as harmful.

After each publicized suicide, the call for suicide awareness manages to slither its way onto the media agenda and enters public and private spheres like a mysterious snake — the bite is usually harmless, but occasionally deadly. When people fail to demonstrate complete awareness when talking about suicide, their words can be dangerous weapons. Furthermore, when the suicides of famous figures push the phenomenon of suicide into the limelight, it usually sparks an epidemic in which there is a distinct rise in suicide and suicidal behaviors, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “suicide contagion.”

Proceed with Compassion

The first problem with current suicide conversations could be solved with more compassion and support thrown behind legitimate awareness efforts.

In most day-to-day conversation, people often talk about suicide with flippancy and reckless abandon. The idea of killing oneself enters casual conversations and serves as the foundation of many expressions and jokes. Lack of empathy and pundits sticking to their opposing political ideologies characterize most reactions to the rapidly rising rates suicide rates and specific suicide cases. This seems to stem from the tendency of society to regard mental illness as contrived, shameful or stupid.

Following the widely reported suicides of Spade and Bourdain, news outlets and social media feeds were littered not only with condolences and prayers, but also with those who inserted their own judgement, which usually involved balking at the celebrities’ selfishness or stupidity for committing the act. Most judgments centered around a lack of understanding and the popular demand to solve the mystery of why these people would choose to end their own lives, especially when young children and families were left behind.

Why does anyone commit suicide? It’s an impossible question to answer. The familiar adage: “before you judge someone, walk a mile in their shoes” may be well known, but clearly not enough shoe-borrowing is going on these days.

Say, for instance, that I’m not very happy and someone tells me I should be happy because there is nothing to be unhappy about — the advice is distinctly unhelpful. Only I know how I feel, but that doesn’t stop the daily statements directed at me that involve assumptions about how I feel.

“I see you survived another day,” my grandpa said, when I come home from a day where I don’t feel like I survived, didn’t completely want to have survived or may still not survive. (I think that’s an assessment only I can make for myself, thank you very much.)

“Are you just quiet or do you not have any friends?” my suitemate asked me, on a day I’ve sweated my way through a major presentation and learned of my rejection from a college I was hoping to transfer to. (They know nothing about me or my life.)

“You don’t seem like the kind of person who would have psychological or emotional challenges,” my doctor said, skipping past the entire mental health section on my health forms for my new college. (How would she know?)

Unless people demonstrate extensive knowledge of the existence of feelings they are not privy to and avoid unfounded judgment when talking about sensitive issues — or any issues, for that matter — they can and will cause extensive damage with their words.

Don’t Feed the Flames

The second problem with the present dialogue about suicide awareness is suicide contagion.

Celebrity deaths not only reveal gaps in suicide awareness and prevention measures, but the lurking threat of a suicide epidemic. The exposure to suicide within one’s family, peer group or through media reports can result in an increase in suicide or suicidal behaviors. Simply the existence of mass media coverage and localized discussion regarding suicides can inflate suicide numbers.

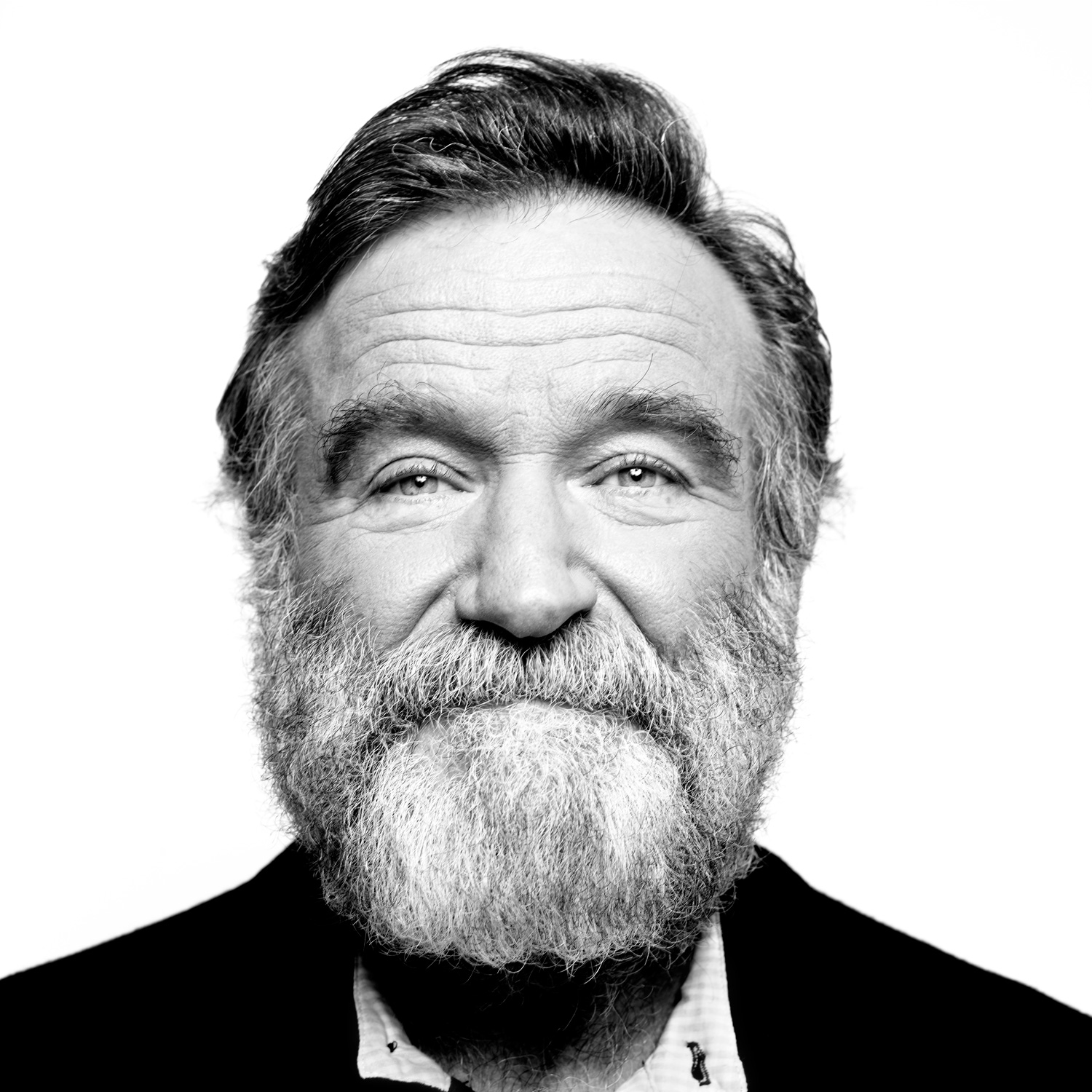

Calls and texts to suicide hotlines spiked after recent celebrity deaths. The number of texts rose 116 percent, and calls by 65 percent. Similar patterns were recorded after the suicides of Chester Bennington in 2017 and Robin Williams in 2014.

Despite the damning evidence, many people refuse to believe that talking a certain way about suicide can, in fact, increase the likelihood of someone committing suicide, as many continue to disperse casual references and terrible jokes regarding suicide that mock the terrifying and morbid issue.

Others, however, share personal experiences of encounters with suicide, which can constitute a more complete truth than statistics and impersonal arguments could ever achieve.

Here is my story:

When I was 14, I enrolled in an outdoor leadership course that involved two weeks of backpacking and rock climbing in the Sierra Nevada Mountains with a number of peers. The group transformed into a tight-knit unit during the journey, and everyone departed with immense knowledge of each other’s feelings, fears, hopes and dreams.

Several months later, I opened Facebook to discover that one member of the group had committed suicide. During the subsequent period of confusion and grief, a miniscule thought labeled suicide appeared quietly on the corner of my un-mapped future. I wondered if they couldn’t close the gap between the life they wanted and the life they had, is it possible that I might not be able to? If they chose death to end this pain, could I?

In the end, it comes down to this: mental health care must be a priority. Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States; 45,000 people die by suicide every year. Yet, suicide prevention only receives about $68 million in funding across the nation, much less than other categorized diseases, such as heart disease ($1.37 billion), cancer ($5.98 billion) or diabetes ($1.1 billion).

Suicide awareness, if more proactive, will increase mental health knowledge, decrease the stigma around mental health and ultimately provoke positive change. Increased awareness and a collective effort to create a supportive environment is necessary in order to effectively address the nation’s increasing suicide rates. Suicide awareness requires more than just the recognition of a problem, it requires action.

In the end, it comes down to this: a person can’t live the life they want if they keep suicide on the table as an option. As YA author Maggie Stiefvater wrote in a series of tweets for World Suicide Prevention Day back in 2015, “I got no closer to the life I wanted because I wasn’t thinking about life. I was thinking about giving up. I couldn’t appreciate the clawing journey to a better life, because I kept my suicide options open. That’s neither living nor dying.”

Careless media coverage regarding suicides can spark a flurry of suicide contagion, but well-intentioned messaging can preserve the notion that support is available. Do not condemn someone for feeling alone, and instead let them know that they are not alone.