Color, one plus one equaling two, the definition of the word “the” — this is just the beginning of a long list of things I innately understand but have a really hard time explaining. Now, the millennial aesthetic can be jotted down too.

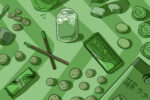

You know it when you see it. Soft pink and clean lines, green succulents and patterned rugs, brass hardware and mid-century modern furniture. Minimalism and open concept spaces — bonus points for exposed brick. Color-coded bookshelves and felt letter boards have changed utility into deliberate design choices. It lives through young adults, upholding its values of poised symmetry and deliberately random choices.

Until recently, I had never heard this spirit and style defined; then I read this piece in The Cut, where writer Molly Fisher summarized it as “The Millennial Aesthetic.” She correctly pointed out that not every millennial enjoys this style, but it encapsulates a design that was born from this generation.

The aesthetic has seeped into just about everything I interact with. Young adults design their apartments based on Pinterest mood boards to create elegant, clean spaces. My own bedroom has a white clothes rack adorned with neutral sweaters and white bedding complemented with earth green from a nearby fiddle leaf fig.

And it’s not just present in interior design, but product, experience and graphic design as well. Businesses and advertisers have latched onto it, filling Instagram feeds and subway ads with soft, pastel visuals that appeal to me for reasons I can’t quite describe.

But the millennial aesthetic is much more than just a design choice; it’s part of a much broader ethos made popular by the minds of the generation that introduced body positivity, pushed back on heteronormativity and advocated for representation in the media. Millennials and millennial-founded companies reimagine the status quo and create products and services that seem empathetic — designed with you, not for you. The millennial aesthetic has gone on to become a watermark to this way of thinking, telling friends and customers alike “we get it.”

Companies like Lola, Casper, Cha Cha Matcha, The Wing, Zola, Otherland Candles and Glossier have cultivated brands created by the ideology of the millennial aesthetic. One look at their websites and you’ll see what I mean. They’ve capitalized on the belief that clean simplicity can create a world that is anything but that: bold, daring and unapologetically unique. They’ve reimagined the human experience, creating businesses that supersede trends into household names.

Even the once most mundane industries are proving they too can play the game. Going to the dentist, save for a few exceptions, might be one of the most universally disliked but necessary activities humans do. Enter Tend, styled like a co-working space with clean interiors and Instagram-worthy corners; Tend is first in line to be the new millennial dentist.

Equipped with Netflix-enabled TVs on the ceiling and a trendy blog where they answer all your dental hygiene-related questions such as how bad weed or seltzer is for your teeth, Tend is working to change the dental industry. But it’s not just through pleasing spaces and design. Hired dentists are salaried and earn bonuses based off of customer reviews.

There’s no longer the need for dentists to up-sell unnecessary services like botox and fillers. Customers have a less stressful visit and practitioners don’t feel the need to constantly pitch and sell. Tend wraps this improved ideology in millennial packaging and design. A silent but understood promise that it’s not just a redefined dental experience but a better dental experience.

Recess, a sparkling water company, claims they’ve “canned a feeling.” Their hemp-infused waters, soft pastel cans and NYC pop-up exudes millennial-ism. Their website latches on to buzzwords and terminology familiar to the millennial vernacular such as “having too many tabs open in our brains” and being “afraid of commitment.”

Priced at $39.99 for an 8-pack, you’d also expect their products to have magical healing powers — and that’s kind of the promise they give you. They advertise better, more holistic ingredients such as ginseng for focus and memory, L-theanine for stress release, and, of course, hemp for a calm mind and body.

They claim their drinks won’t leave you tired or wired, promising to help you be “the you you are on your best days.” Reclaiming the mid-afternoon pickup from coffee or energy drinks, Recess is a better caffeine solution, as told by their brand.

This is the promise of the millennial aesthetic, that anything painted in this style will push boundaries and break down walls for structural change in their marketplace. It’s not a bad commitment; in fact, it should be welcome. But the overuse of the aesthetic has caused people to question its validity and question the products it decorates.

People either love it or hate, or they love to hate it. The sheer fact that something is popular among the masses is enough for others to reject its authority — that was essentially the entire hipster subculture. But once everyone collectively likes the “most obscure” or dislikes the “most popular” the search for the unknown and the rejection of the favored becomes its own inadvertent, but unmistakable, trend. You’re torn if you should like it, and question why you do.

As Molly Fisher wrote in her essay for The Cut, “We resent its absence (Why is this restaurant website so crappy?) but also resent its allure.” The promises packaged in stress-relieving colors and pop-centric typography are lofty, and the biggest promises often leave room for the biggest disappointments. The products and services encourage out-of-the-box thinking, boxed into one aesthetic.

This isn’t to say there’s anything inherently wrong with the millennial aesthetic, simply that it sells because it’s young, new and full of hope. For lack of a better word, it’s trendy. Maybe we buy into it because we like this new world these companies are creating. Maybe we resent it, longing for a simpler time when Instragrambility wasn’t a consideration for products and services.

What will change when millennial is no longer synonymous with young, when the brands and their founders aren’t either? Will the millennial aesthetic still represent the promise of a better tomorrow or simply the dreams of a distant past?

But for now, pastel pink is the new black — and it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon.

The millennial aesthetic is all about embracing minimalism, comfort, and functionality while still maintaining style. It’s about creating spaces that are both practical and visually appealing, often using soft, muted colors, and natural textures. A great addition to any millennial-inspired home is a plush shaggy rug, which adds warmth and a tactile element to the space. It’s the perfect way to balance the sleekness of modern furniture with a touch of cozy, laid-back style!

Great post