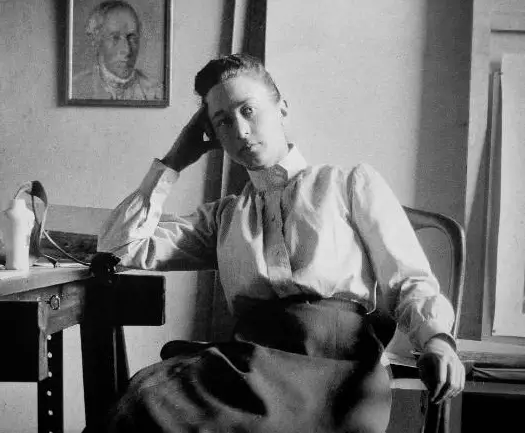

The Swedish artist, abstractionist and mystic Hilma af Klint, who has been dead for 74 years, has been making waves this year after she landed her first major solo exhibition in the United States. While you can’t talk about abstract art without mentioning Wassily Kandinsky, who is hailed as the father of abstraction, Klint is now in the process of stealing Kandinsky’s crown.

Kandinsky painted his first abstract, “Composition V,” two years after theorizing the meaning and spiritual journey of abstraction in his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” in 1909. Abstraction was a revolutionary art form that defied millennia of representational art and challenged a rising consumerist society. Little did he or anyone know that Klint had been journeying to the spiritual realm and painting abstract art since 1906, well before Kandinsky even conceived the idea, meaning the first abstractionist wasn’t a man at all.

Born into a Protestant family, Kilnt became emerged in philosophies of religion and spiritualism that focused on inner truth and divinity and achieving high mental and spiritual clarity. Around 1896, she joined a spiritual group of female artists called “The Five,” who attempted to contact the spiritual realm and communicate with higher spirits they called the “High Masters.” They documented their efforts, which included prayer, studying and reading the New Testament, automatic drawing and writing, and séances.

During a séance in 1905, Klint wrote that she heard a voice instructing her “to proclaim a new philosophy of life” and to paint “on an astral plane.” This call inspired her to create what would have been radical works of art between 1906 and 1907, called “Primordial Chaos,” a series of small, abstract paintings featuring cool tones and sharp, yellow, geometric and organic shapes, such as shells, flowers and snake-like figures. In 1907 came “The Ten Biggest,” a large, colorful canvas made up of circles, spirals and calligraphic shapes. Her colorful, mystical masterpieces now adorn the walls of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

In the 1930s, competition waged over who was the first abstract painter, with multiple early abstractionists contending for the title, including Kandinsky, Robert Delaunay, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova and Kazimir Malevich. But there was no sign of Klint.

Sweden was one of the earliest countries in Europe that allowed women to study art, helping pave the way for the future artist, who decided to study art at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1882. She was primarily known as a landscape painter, and though she exhibited her representational work, she never revealed a single abstract piece out of the near 200 she painted. Klint had no desire to exhibit her abstract work, which kept her out of the debate and spotlight for decades, and her spiritual practices have continued to impact her place in history.

Even after her death in 1944, acknowledgement of her work was further delayed by her desire to keep her artwork hidden. Her will requested they be kept away from the public eye for 20 years upon her death, claiming the world wasn’t yet capable of understanding them. When that time was up, her family had trouble finding a venue that would show them, until 1986, when the Los Angeles Museum of Art included her work in their exhibit “The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890-1985.”

It took 42 years for Kilnt’s work to be appreciated in person, but she maintains a following of skeptics that push against crowning her the mother of abstraction. Although Klint and Kandinsky share a similar spiritual connection to art, her spiritual outlook has tainted her reputation in the art world.

Klint said spiritual forces were directing her hand, as if a conduit for higher powers, and it was this spiritualistic outlook that prevented her inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition, “Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925,” which ran from 2012–2013, despite her pieces being clear abstract paintings.

The exhibit’s curator, Masha Chlenova, told Artsy that inclusion in the exhibit required the artist to “formulate their practice as a conscious rejection of any reference to the outside world.” Klint’s claim of mystical intervention invalidated her work, but others argue that her approach and spiritual perception shouldn’t shut her out.

Los Angeles curator Maurice Tuchman told The New York Times, “‘Spiritual’ is still a very dirty word in the art world.” It’s a misunderstood and intolerable concept that requires time to overcome, yet Klint’s spiritual journey isn’t that far off from Kandinsky’s or his theories of the abstract in “Concerning the Spiritual in Art.”

Kandinsky makes a clear distinction between the external and internal, associating religion, science and morality with crutches. To Kandinsky, these things have no connection to the soul or one’s spiritual awakening, and once pulled out from under man will prompt him to let go of the external and look inward. He emphasizes the importance of man turning his attention within himself, to the internal truth. “Literature, music and art are the first and most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt,” he said.

Although Kandinsky didn’t associate his idea of spiritualism with another realm or acted as a spiritual channel between the natural and supernatural, like Klint, he understood the power and necessity of spiritualism. They both believed that something detached from the materialist world was involved in creating abstractionism, and as Kandinsky explains in his book, one of the mystical elements of creating art is a call inside every artist, yearning for expression.

Klint expressed this yearning and inner power in one of her journals. “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force,” she wrote. “I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

The artist’s deep spiritual connection and inner visions, which can be argued as her internal truth, inspired revolutionary works that many perceive as a visionary journey of faith but are undoubtedly abstract.

Although Kandinsky was also inspired by religious and spiritual philosophies, what sets these artists apart and why some circles refuse to embrace Klint into the fold of abstractionism was her involvement in an occult.

Despite the controversy, the Guggenheim Museum recognizes Klint’s work as a detachment from the physical world or any form of representation. According to the museum, “It was years before Vasily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, and others would take similar strides to rid their own artwork of representational content.”