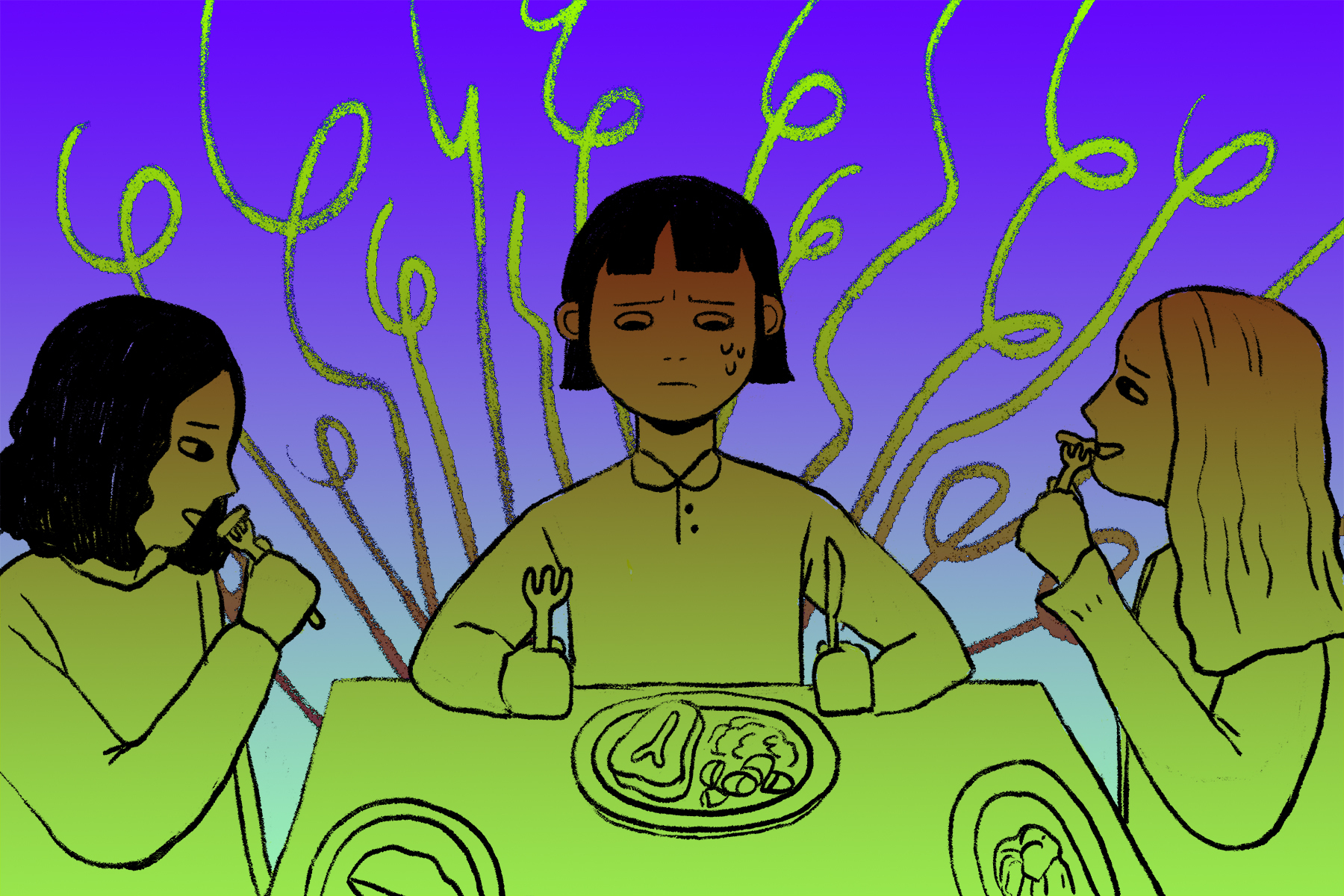

Have you ever felt the guilt of eating too much in front of other people? Perhaps feeling guilty after eating more than your friends or denying a second serving at dinner even if you’re still hungry?

When I was a child, my cousin and I always fought over who got more food, sneaking more chicken nuggets onto our plates and laughing at the other for getting less. As we grew up, something shifted. Rather than wanting more, we wanted less. Although it was never spoken aloud, we food-shamed ourselves in fear of overindulging in front of the other and being viewed as unhealthy or gluttonous.

The society we live in makes comparing plates normal, as if everybody should eat similarly, and if someone eats too much, too little or not the right kind of food, they are subject to judgment. This culture around undereating in fear of judgment from the self or others is normalized within our society, especially among women. Although most people may not notice what is on another’s plate or how much they consume, the fear of judgment from others still limits people from eating what they normally would if they were alone. Food shaming others is one way to project one’s internal thoughts about food choices, and it creates a culture of constantly monitoring food choices and the amount of food consumed.

Michelle May, author of “Eat What You Love, Love What You Eat” told Robin Hilmantel from Women’s Health: “Here’s the problem: When we judge food as being ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ we also judge ourselves and other people as ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ depending on what we ate.”

Messages on what we should eat and what our bodies should look like are received at a young age through parents and media and are perpetuated by social media and friends. There are millions of ads dedicated to dieting, articles about eating healthy and influencers flaunting bodies that are deemed perfect by society. They unconsciously tell us that there is a “good” and “bad” dichotomy associated with healthiness. However, the world hosts many ways to be healthy — mentally and physically — and it will not look the same for everyone.

Hilmantel further wrote that obsessing over “what you ‘should’ eat and beating yourself up about consuming certain things that don’t fall into that category gives credence to the harmful belief that you can’t trust yourself and your body to make your own food choices” and that it can turn into “an obsessive and dysfunctional relationship with food and, in some cases, even more severe problems like disordered or secretive eating.”

The college atmosphere normalizes this disordered eating culture and glorifies all-nighters and overworking. It is seen as more successful and productive to skip breakfast in order to study rather than spend the time to make and eat a full meal. Hearing someone say, “I only had an apple today” is normal and often brought up as an accomplishment, something that reflects all of the work that has been completed.

In an Instagram post made by Impact, it is estimated that “12-25% of college women will struggle with an eating disorder, although many will never seek treatment.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CDPjxzwBtb-/

Healthline wrote that disordered eating occurs in college more frequently than in any other environment because of higher education’s newfound academic, social and familial anxiety, as well as the exposure to more people, which increases the risk of comparison.

For example, watching another student excel academically by constantly studying and barely eating might make another student feel inadequate if they don’t practice the same habits. Or perhaps watching a friend drink on a night out pressures everyone else to drink as much. The anxiety and societal pressures put on eating force people to mistrust their own bodies. Every body is different, requiring different needs, so comparing oneself is useless.

“We as college students need to be better at creating a space for us to learn how to develop healthy habits on our own, without the pressure formed by an unhealthy college view of what we need to put (or not put) in our bodies to have the lifestyle we want,” Ava Dunwoody wrote in her opinion article.

It wasn’t until later in my college career that I figured out what was wrong with this phenomenon of limiting myself in front of others. I moved into an apartment with my best friend who emphasized the importance of eating enough throughout the day. I have always been self-conscious about eating with others because of the views of weight and food that have been put into my head by society, but my friend encouraged a nontoxic environment in which we both sat down for dinner regardless of how much work we had to do. I hadn’t considered the regulation of my eating with others until I had a friend who asked if I ate lunch, and who never commented on what I ate or how much.

One way to fight against the negative thoughts surrounding food is to recognize that all bodies are different, craving different foods at different times. It’s easier said than done, but noticing when the judgmental thoughts begin in oneself as well as in others is the key to ending the cycle of negative behavior. When seeing a friend eat less or even more, it can be easy to think negative thoughts, but changing the thoughts can alter such behavior: “I worked hard, so I deserve to eat a big meal” or “I ate an hour ago, but she must not have, so it’s okay that she is eating more.” A change in language offers more positive thoughts around eating.

Another way to combat food shaming is to allow oneself to gain pleasure from food. While forming healthy habits is great for the mind and body, it is just as necessary for one’s mental health to not beat oneself up about eating foods labeled unhealthy, such as French fries or cookies. Finding pleasure in foods is not something to be ashamed of — it only creates a negative view of the self and the food.

There has been a push to normalize all types of bodies as well as eating habits. In a post by Feminist on Instagram, a photo compares two identical plates of food, calling them “His” and “Hers.” The caption says, “Those ‘His’ and ‘Hers’ meal photos where ‘hers’ is always hundreds of calories less than ‘his’ are B.S.. They promote stereotypes and basic needs equations that are rarely accurate.” Looking at more realistic and relatable content on media allows viewers to not feel ashamed about themselves, and to not feel alone in a world that paints beauty and health with an unrealistic standard.

Chelsea Peng from Marie Claire summed it up perfectly: “Basically, eat what feels right for you and really enjoy it — and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.”