On May 31, 2020, Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, better known as Christo, passed away. He worked with his wife, Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, who passed away in 2009. The Bulgarian artist’s death marks the end of the couple’s career, which spanned over 50 years. They were renowned for their large-scale public art installations.

I’ll be honest. I didn’t hear much about the two artists until Christo’s death last month, but the more I look into their artistic practices, the more curious, impressed and inspired I became. The two weren’t conventional artists by any means, though Christo did attend the Fine Arts Academy in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Instead, the two worked with what could be characterized as sculptures, but even that description would be a gross simplification. Christo and Jeanne-Claude created site-specific, monumental art installations that used fabric and readymades — all of which were seamlessly integrated into their environment in a process that took decades to realize.

Some of their more prominent works include “Wrapped Reichstag,” in which 100,000 square meters of polypropylene fabric covered the German parliament for a period of two weeks in 1995. Another is “The Gates,” in which 7,500 panels of saffron fabric dotted Central Park’s walkways for 15 days in 2005. If you haven’t heard of them, that’s completely understandable. Their installations were temporary, making them hard to view in-person, and several were on display before many of us were born.

However, the effects of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s art are far from temporary. Just looking at photos of their art is awe-inspiring, and they have more than 20 projects of this caliber throughout the world. All were in public spaces, and many were wrapping projects similar to that of the Reichstag, like the “The Pont Neuf Wrapped” in 1985 and the “L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped.” The latter was originally planned for this year, but it was postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The artists have an equal number of works that don’t involve wrapping, including the aforementioned gates, a piece that suspended a fabric walkway on Italy’s Lake Iseo and a series of metallic umbrella structures in California and Japan.

Yet, what is most inspiring about Christo and Jeanne-Claude is that they financed these projects entirely by themselves. They didn’t accept any donations to offset the costs of these projects, which usually ran into the millions, nor did they rely on ticket sales.

Their artwork was open to the public, and they didn’t receive any royalties from reproductions of their creations. Rather, Christo and Jeanne-Claude sold sketches and preparatory drawings to fund the costs of fabric manufacturing, feasibility studies and labor. Volunteers were not really volunteers because Christo and Jeanne-Claude paid everyone that helped.

In addition to self-funding their monumental fabric projects, the artists also emphasized their pieces’ lack of symbolism or purpose. Their art was just about creating “joy and beauty.” As someone used to finding hidden meanings in any artistic work, whether that be in literary classics or in religious paintings, it’s unnerving to see Christo and Jeanne-Claude profess that their sculptures don’t allude to something.

But while Christo and Jeanne-Claude state that their art is simply for pleasure and aesthetics, it would be wrong to ignore the tedious processes that the two endured, often for decades at a time, to see their projects come to fruition. While our end results often face the most praise or scrutiny, the years leading up to these projects contribute just as much to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artistry.

Many of the installations, for example, sound impossible to have been approved in the first place. How could two individuals gain access to our country’s most popular urban park? How could they have obtained similar permissions in other countries as well? Does this feat speak to the unifying influence of art, or does it speak to the relentless, almost dogmatic, manner in which Christo and Jeanne-Claude created their art?

When “The Gates” was on display in Central Park, many critics ridiculed Christo and Jeanne-Claude for what seemed to be a useless exhibit. So, the couple’s work likely points toward the latter, but it has steadily become more grandiose over time as they have established a reputation for themselves among art enthusiasts and public officials alike. The artists were able to accomplish what many governments cannot do today.

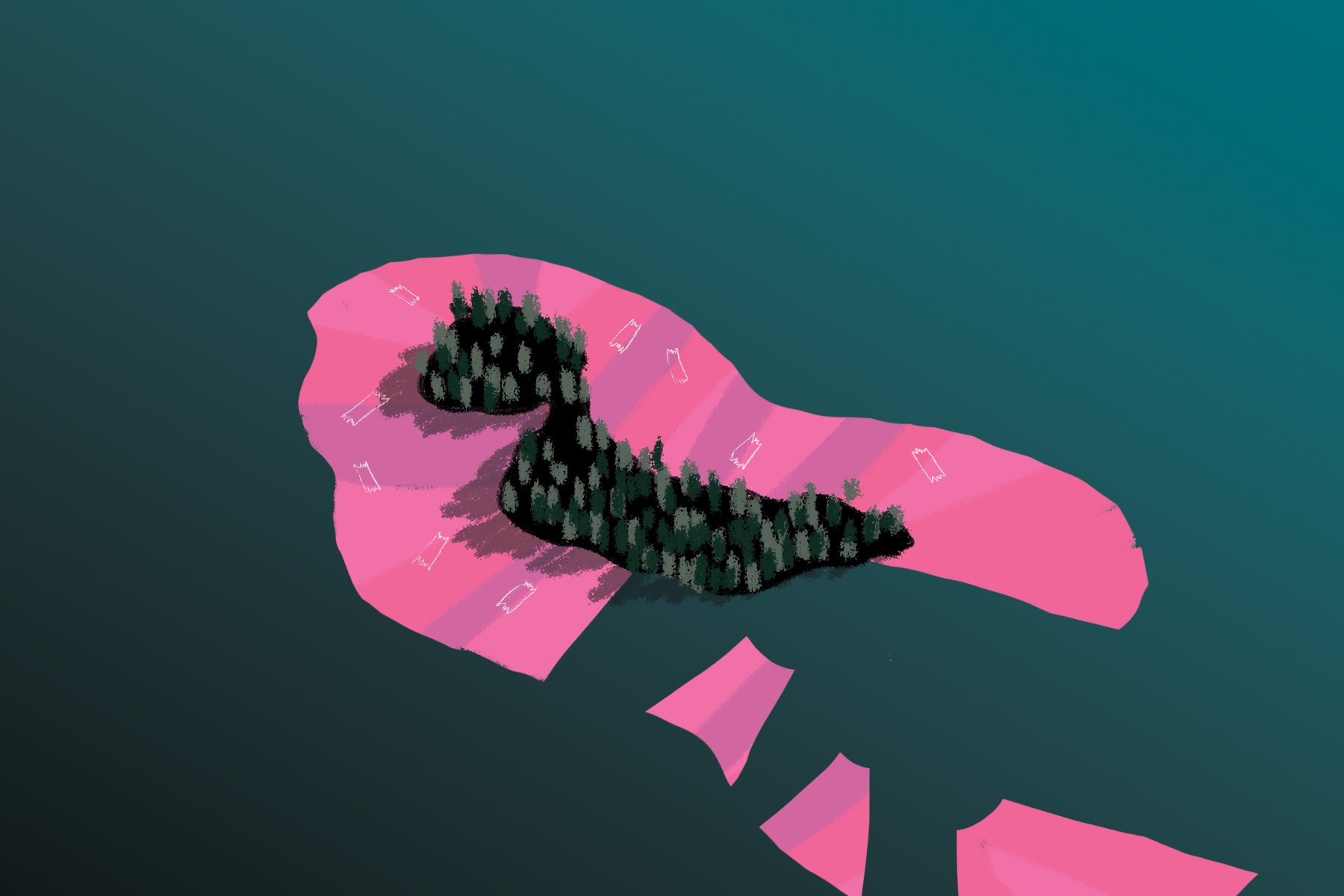

It’s also important to consider that Christo and Jeanne-Claude were environmental artists. When working on “Surrounded Islands,” a 1983 project that wrapped 11 islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay with pink fabric, some of the islands were pointedly dubbed as “beer can islands” for the number of trashed bottles left on the ground. The couple left the island cleaner than before and, as they did in all of their other projects, repurposed the fabric and melted down metals for future use.

All these practices — working tirelessly, sustainably and solely — speak to the strong record that Christo and Jeanne-Claude have with following through on what they loved to do. If not for the art installations, one can admire them for their consistency and work ethic. Though, it does feel uncompromising at times. Reportedly, the two never flew in the same airplane, so that if one crashed, the other could continue their work.

Maybe the reason Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s art resonates is because it rejects so many values that society instills. We’re taught that success implies permanence, and that memorialization is a way of honoring people’s accomplishments. Christo and Jeanne-Claude reject these notions, instead embracing what doesn’t last forever. There won’t be a museum where you can see their magnum opus in-person like you can with the “Mona Lisa.”

Capitalism tells us to never turn down an opportunity for commercialization, but Christo and Jean-Claude were never concerned with making a profit from their projects or accumulating wealth. Perhaps that is how they’ll be remembered.

Although they have passed away, Christo and Jeanne-Claude planned for their art to continue in their absence. The Arc de Triomphe will be wrapped from September 18 to October 3, 2021, and that might be the best way to experience what the artists wanted to convey.