The racist violence that claimed the lives of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor has sparked protests every day for the past two weeks, spreading an uproar across all 50 states. For a week straight, social media has served as its own site of mass demonstration against racism. Users of Instagram, Twitter and Facebook have been using their pages to express solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, sharing donation funds that support protestors directly and holding local precincts accountable for police violence by circulating videos of abuse toward protestors.

Even with so many voices urging for change, a troubling minority of people I interact with both on and offline decided not to speak up. For various reasons, some non-black users have decided that amplifying the Black Lives Matter movement online makes them uncomfortable, or that they feel safer staying quiet.

But don’t be mistaken: Online silence sends its own message, and for black users, it is received as one of callous apathy. Here’s why real allyship involves publicizing antiracism on your personal digital platform.

1. Expressing Solidarity Online Is Symbolic and Important

To anyone with black friends, associates or coworkers, actively ensuring that your support for them is visible as the entire globe reacts to George Floyd’s death should be at the top of your list of how to respond to this moment. Your black friends should not have to search for your acknowledgment of our vulnerability online, and posting can show that you are listening and doing.

If you participate in the movement online, black people don’t have to wonder if, deep down, speaking out against racism actually bothers you.

Many African American users like myself note white people’s refusal to take an antiracist stand online as a form of silence. The term “white silence = violence” is amplified around racial injustice to describe the ways that white people consent to racism by refusing to condemn it. Condemning racism involves challenging anti-blackness in public ways, especially online, where any one of us has at least dozens of people viewing what we post.

By refusing to join black people’s cries for an end to racism online, white people join the silent majority that enables state violence on African American communities. By opting out of expressing solidarity with black people online and publicizing #BLM content, white people let their black friends down and signal complacency with the status quo.

2. Posting Online Is Quick and Easy, but Still Impactful

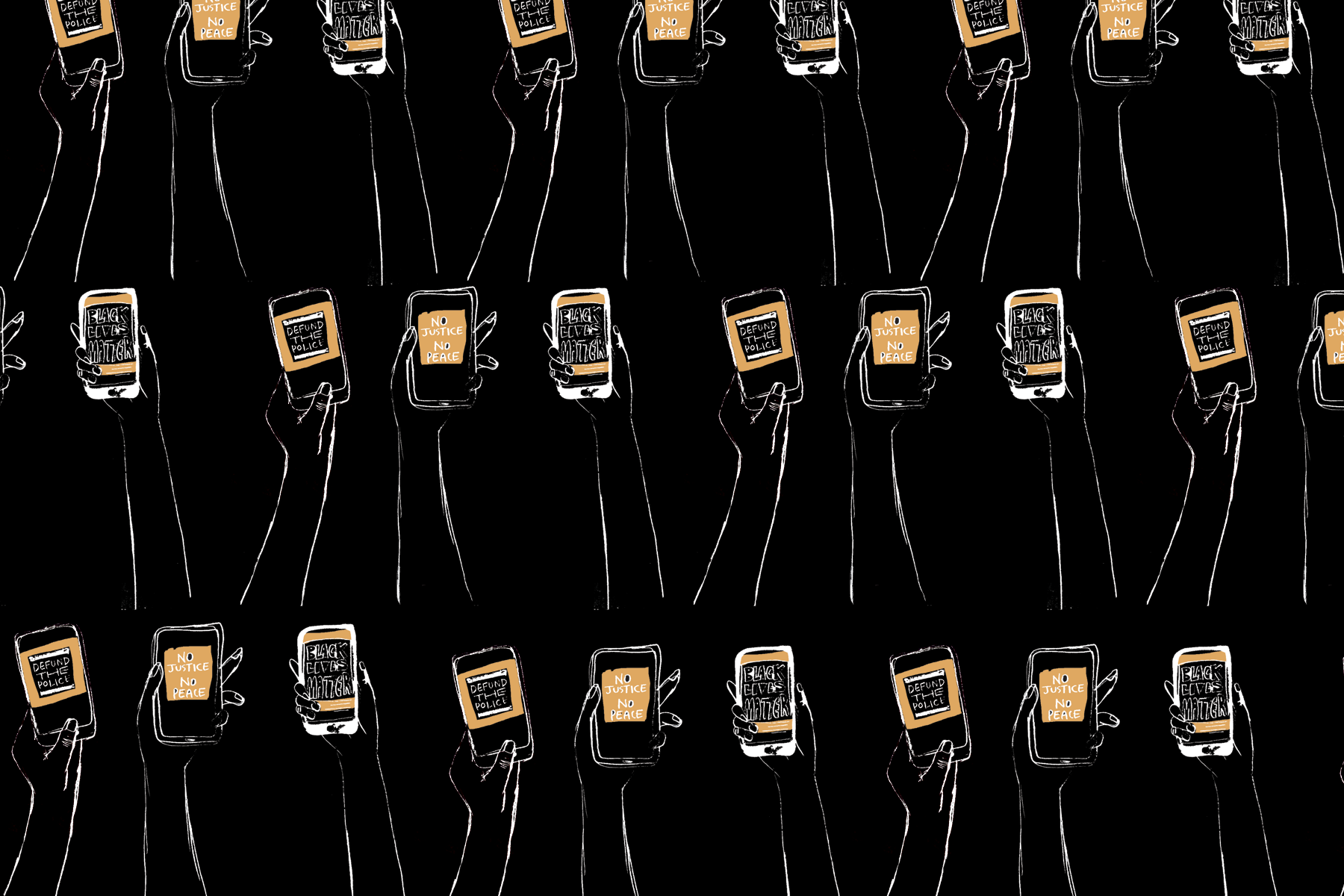

In our digital age, social media has become an important tool of resistance. Instagram and Facebook represent some of the lowest stakes arenas where students can stand in opposition to the system, and thus stand with black people by affirming #BlackLivesMatter.

When non-black Gen Zers refuse to engage with the virtual spaces of protest, they are doing more than protecting themselves from potential clashes with friends and family. By not posting, social media users withhold valuable exposure from the efforts of black activists — efforts that support black people’s very right to live.

Social media has shaped the Black Lives Matter movement by mobilizing thousands through a hashtag. Posting online facilitates the spread of critical information that supports the movement, so it is important to ask yourself, “What is stopping me from posting?”

At the same time, opting out of sharing relevant information online protects non-black students’ followers who hold racist views from engaging with anti-racist perspectives.

Staying quiet online is not a neutral act; it reveals that your allyship only goes as far as you can be protected from the minuscule, or even moderate, social risks of losing followers. As we ride the waves (or, the flames) of a watershed moment of protest, non-black users who are active online but avoiding posting or sharing racial content are implying that black people, even when we are being murdered, aren’t important enough to affirm our humanity on their platforms.

3. Black People Are Using Social Media to Push the Movement Forward

Black people are posting, and generally post more about race on social media, even under less dire circumstances. If black people have to disrupt their regular content and throw away their Instagram aesthetics to advocate for their lives, then allies, especially white ones, should at least be doing the same. White people benefit from the state that decides black bodies are disposable.

A simple, yet still meaningful, way to resist the anti-black racism that poisons U.S. society is to publicly acknowledge that our deaths are something that should infuriate you, and to affirm our humanity, as well as our crucial contributions to American democracy and culture. A requirement of genuine allyship is deciding that speaking out on whatever platform you have is absolutely necessary, and that voicing public support for black communities is worth standing out.

4. Publicize That We Deserve Protection

It is important to accept that black people’s immediate protection relies on public, interracial condemnation of the violence done to us, and not, as some social media activists have described, white people’s private self-improvement goals.

One of the more heartening aspects of our current period is the mass sharing of various re-education syllabi, focused on unlearning anti-black biases and incorporating anti-racism work into one’s daily life. The urgency of black death means every person needs to broadcast their support for black lives and movements demanding an end to systemic violence to as many people as he or she can.

Though black people have critiqued the insulting performativity of “virtue-signaling” — advertising one’s non-racism by posting online without taking action off the internet — awareness of that critique is not an excuse to refrain from posting.

Privately donating to George Floyd’s memorial fund may not be performative, but it also fails to use the platforms guaranteed to almost all of us — like a personal Instagram page and a Facebook account — to honor his life, which was publicly treated as disposable.

Working for equality has to be about more than feel-good actions; it has to be about counteracting the narrative that black folks’ lives are disposable. If you’re not actively disagreeing with the master narrative of black disposability by advocating for racial justice online, you’re perpetuating a dangerous story of white consent in the face of black death.

5. Posting Can Start Important Dialogues

Part of the work of anti-racism involves non-black students starting conversations about white privilege and white supremacy with the people in their social networks, especially older family members. White people are significantly less likely to encounter race-related content on social networking sites. By posting, non-black people at the very least put the struggle for freedom on the radar of privileged groups.

To open conversations about white privilege and anti-blackness in your own circles, you have to do more than “like” popular posts about racism. You need to amplify the voices of black activists and other anti-racism advocates by bringing the conversation directly to your audience — your social media following.

Since social media platforms like Facebook often connect us to an audience of close friends and distant family members alike, non-black users especially can initiate crucial conversations within their circle by simply influencing their followers’ newsfeeds. Making a single person rethink racial inequality in the United States is worth the post.

The average person has eight social media accounts, meaning we all have a voice online. Some have larger networks than others, but we all have online audiences. Staying silent within digital landscapes like Facebook and Instagram may feel like hiding, but it is a bold statement of indifference, even if you don’t intend it that way. With black lives on the line, choosing not to speak up online isn’t just bad allyship, it’s racist.

Pushing equality forward involves uncomfortable and inconvenient steps for everyone, and most especially for black people, who bear the violent consequences of systemic anti-black racism. If speaking up online makes you cringe for any reason, do it anyway.