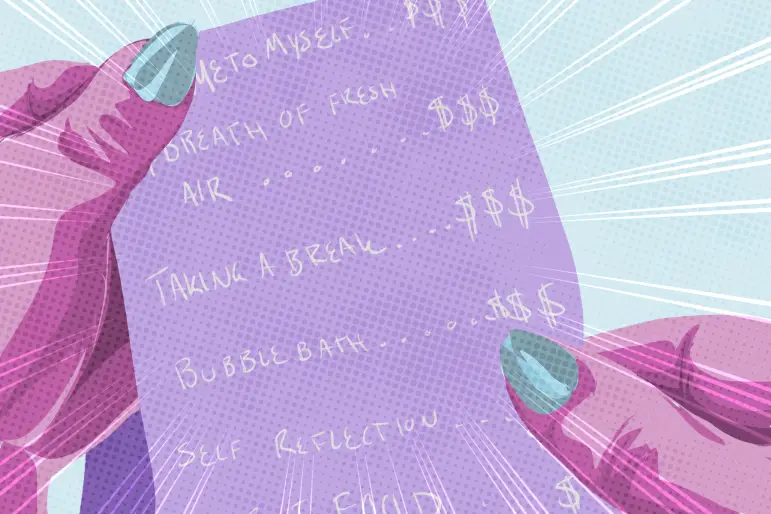

Bubble baths, face masks, unhealthy food and procrastination. Binge-watching that television show instead of finishing a homework assignment or studying for an important test tomorrow. Canceling plans last minute because you no longer feel “up to it.” What thread connects these concepts? The nebulous modern idea of self-care. The definition varies from person to person, of course, but what many in modernity view as self-care focuses more on the “self” than the “care.” More on the short term than the long term. But why? How has this concept that looks so positive on paper begun to hold the possibility of so much harm?

To find the true origin of self-care, a trip to ancient Greece is in order. Socrates was a prominent Greek philosopher who lived from 469 to 399 B.C.E. He pioneered the idea of the Socratic seminar and hardly wrote any work, yet inspired people through his teachings. Socrates’ life was primarily documented by his student Plato, who recorded his teacher’s words to preserve his theories on virtue and the nature of evil, among other topics.

One issue Socrates meditated upon was the importance of self-care, or “care for self” as Socrates put it. In Plato’s “Alcibiades I,” Socrates defines self-care as “‘tak[ing] care of the self insofar as it is the ‘subject of’ a certain number of things: the subject of instrumental action, of relationships with other people, of behaviour and attitudes in general, and the subject also of relationship to oneself.” As Socrates believed that the soul was the true self and wholly separate from the body, he stressed the importance of knowledge of your soul in fully realizing your potential and becoming the best version of yourself.

Moving further in history, observers can see self-care become more politicalized through the adoption of the concept by a Black Power political organization called The Black Panther Party. In the 1960s, the Black Power movement gained traction in America, mainly thanks to the efforts of The Black Panther Party. The group focused on the holistic needs of Black America, including childcare, food security, banks and even medical care; they stressed the importance of self-reliance, creating an alternative to the heavily racist institutions designated by the American government for Black people to use. This work was tiring and resulted in multiple assassinations and governmental sabotage of the organization’s plans, but the work was necessary nonetheless.

Audre Lorde’s full, modern definition of the word “self-care” also contributed to its politicization. Audre Lorde was a Black feminist, poet, activist, lesbian and mother who recognized the importance of hard work. She examined and challenged systems of power through her writing, including “Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches,” a book containing Lorde’s most impactful prose, and her poem “Coal,” in which she redefines her Blackness as something beautiful and meditates upon how politics affects language and perception. As an activist, taking time to care for yourself arguably carries the same importance as the work itself. Lorde believed in radical self-care, which she defined as:

“Crucial. Physically. Psychically. Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

In modernity, how has self-care shifted from a tool of “political warfare” to another mode of consumption? Social media plays a large role. It thrives off of the consumption of its user base (i.e. social media platforms can only exist if there are users consuming ads), so it is no wonder many social media sites have become new platforms for brands to market themselves, whether that marketing comes from the mouths of friendly neighborhood YouTubers or from sassy, meme-fluent brands on Twitter. As brands attempt more outlandish publicity stunts, such as starting internet rap beefs with rival companies, these same brands have also been observing the language young people use online and tweaking their marketing as a result.

The “self-gifting” that brands have been encouraging since the 1950s has gone from encouraging consumers to impress their neighbors or keep up with the Joneses, to using their products to satisfy a deeper purpose, to both empower and express themselves with their dollar. By packaging consumption as radical and appropriating Lorde’s theory, brands are able to cloak their oftentimes useless products in the veil of political action under the guise of “self-care.”

Another reason self-care has become so watered down is because of the social media-driven goal to achieve a perfect aesthetic. With many forms of social media like Pinterest, Twitter, TikTok and Tumblr come an overvaluing of aesthetics. A prime example of this drive to aestheticize everything came during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the youth began to romanticize the different vaccines, dubbing Pfizer the “hot person” vaccine and looking down upon the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. The obsession with appearances has tainted the view of true self-care, with face masks and bubble baths taking the place of cooking a simple meal or going to bed early. The former are more aesthetically pleasing, clearly, and make for better social media posts.

This stylized version of self-care focuses on instant gratification and pleasure, what the YouTube channel The Financial Diet defines as “Instagram self-care”; it can include practices like procrastinating or eating foods that make you feel good in the short term but may not have nutritional value. Just from the first line of her definition, readers can see the stark difference between Lorde’s self-care, where “not self-indulgence” is a main tenent, and the modern “treat yourself” mentality that prioritizes consumption.

The focus on the immediate may not entirely be the fault of the youth, however, as prolonged technological use has been correlated with a shortened attention span. Many young people are understandably more concerned with the present than the future, which affects how one cares for themselves. This superficial self-care focuses on immediate gratification: doing what one wants in lieu of what one needs to do in order to succeed. There needs to be a redefinition of self-care on social media, a clarification that true self-care is not fun in the short term but is important in the long run. True self-care can be boring and tedious, like finishing an essay early or finding financial wellness, but is crucial to maturity and fulfillment in life.

Of course, the purpose of this article is not to completely discourage and shame the “treat yourself” mentality in the slightest — rewards for hard work and accomplishments are necessary. At the end of the day, there’s nothing wrong with enjoying bubble baths or taking time for yourself, but what’s important is being aware of how larger economic forces and marketing affect what constitutes self-care. In order to reclaim the concept, young people need to re-center themselves and focus less on consumption and more on true fulfillment.