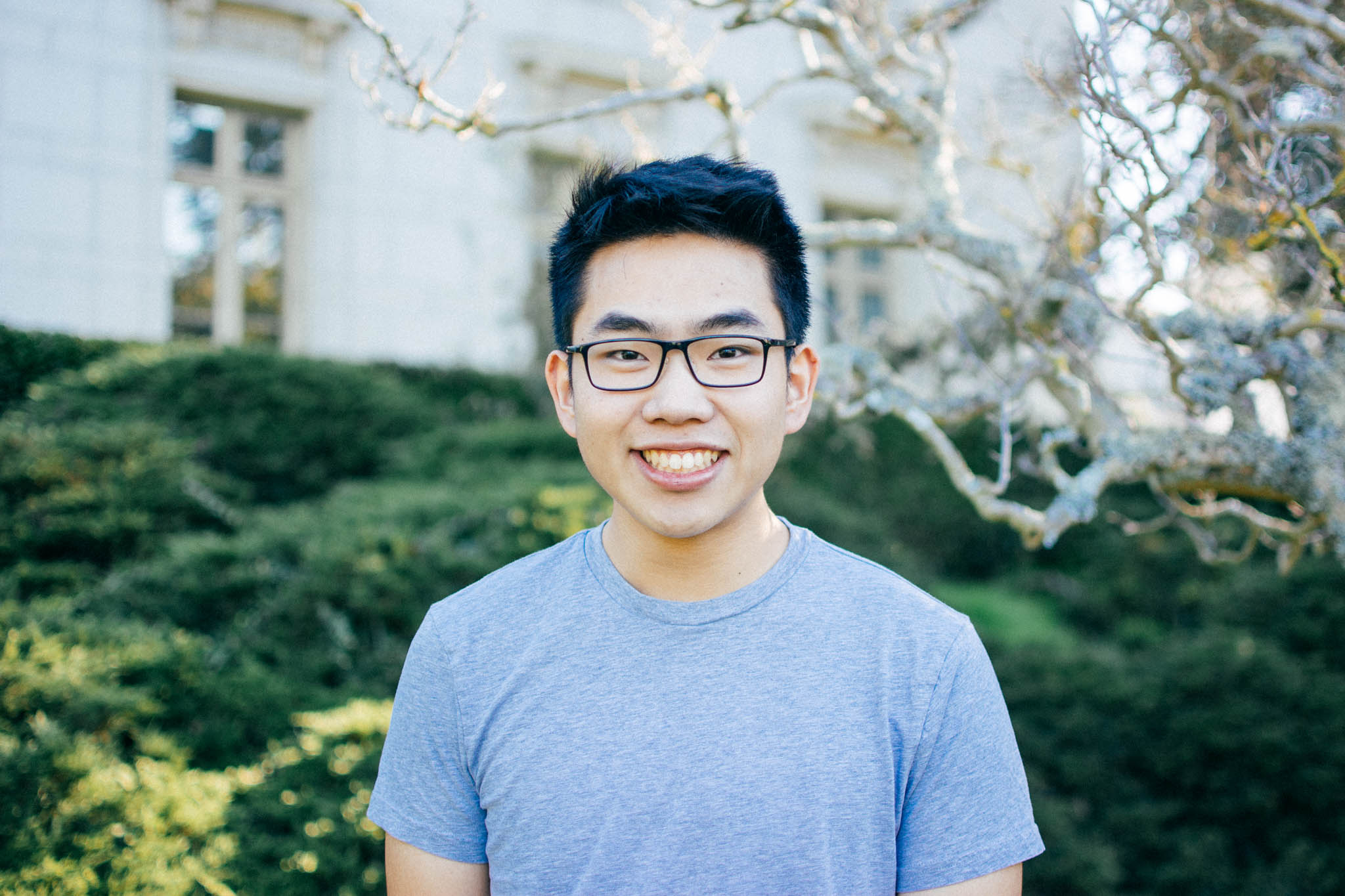

If it wasn’t for a personal experience with his healthcare provider, Nolan Pokpongkiat might’ve been studying software engineering and his organization, The Helix Group, wouldn’t have been born. Now a sophomore at the University of California, Berkeley, he founded Helix to address the lack of diversity within the healthcare field and encourage underrepresented students to explore degrees in medicine.

Sparked by encounters outside of the classroom, Pokpongkiat took the lessons he learned beyond the university’s walls and created Helix with five other undergraduates from his school.

The organization provides a three-step approach that hopes to inspire more minority students to pursue healthcare careers in order to combat the challenge of navigating cultural barriers to provide the best care possible for afflicted patients.

The first step is a week-long summer program taught by UC Berkeley undergraduate recruits. Local high school students from around the San Francisco area will study a carefully student-curated curriculum. They also will have the opportunity to participate in hands-on lab experiments, learn from lectures, earn a CPR certification and connect with local professionals.

The second step is a four-week internship that rotates students through a shadowing program so that they can gain insight from real clinic operations. Lastly, students will meet at the end of the summer for the Helix Symposium to share their experiences and knowledge.

The idea came to fruition over the summer when Pokpongkiat and a group of friends were working as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs). They recognized the lack of diversity in numerous fields but did not fully become aware of it within their own until they researched further.

They discovered that African Americans, Hispanics and other ethnic minorities made up approximately 30 percent of the population but only comprised about 10 percent of doctors. It was the summer experience coupled with the absence of a preexisting student organization focusing specifically on the issue which led him to conceive the program’s concept.

“What we want to do is basically diversify medical education, and therefore by extension, increase the cultural competency of doctors once they graduate medical school so they can provide better care for their patients,” he says.

Presently a molecular and cell biology major, Pokpongkiat was propelled into the world of medicine from an early onset.

“My parents both work in healthcare. My dad is a doctor, and so from a pretty young age I’ve been put onto the path of going into medicine, but it wasn’t really until college when it became solidified for me,” he says. “I think growing up, throughout elementary school, middle school [and] high school I was like ‘Okay, yeah I’m going to be a doctor,’ but I didn’t really know why.”

He deliberated between medicine and software engineering, two fields he both enjoyed and excelled at, before ultimately deciding to pursue a health-related degree after an experience he had with his personal healthcare provider.

“It wasn’t until this past break, when I went to see my doctor for surgery, when I was really touched by how comfortable a doctor can make you feel in a time of [uncertainty] about your situation [and] about your health.”

At the core of his career choice resides an unconventional motivation: a desire to empathize with the people he serves, particularly underrepresented groups. Understanding people of particular backgrounds forms the basis of connecting medicine and personal engagement with patients.

He recounted a time when his mother injured her arm and visited a few doctors before voicing her frustrations because she didn’t feel that they thoroughly understood her and her background. This prompted him to delve into the issue of doctors not being unable to care for their patients in a “culturally competent way.”

One of the difficult questions he posed to students is, “At what point are you going to learn to understand people from different cultures…and interact with people from different backgrounds if you’ve never been exposed to it in your education?”

A challenge he has faced in the creation of the newly formed organization resides in the starting operations. He voiced the difficulties of pitching the idea to doctors at hospitals because of the lack of prior, tangible work thus far.

However, he cites that trusting in the team’s drive and idea along with showcasing a clear plan of implementation has garnered significant success.

“We interviewed our applicants, and we’ve found that there are so many people who care about the same things we do.” Pokpongkiat asserted that Helix received over 50 applicants and that the program has been well received by students, doctors and professors alike.

Speaking with conscientiousness toward Helix’s future, he says, “We’re keeping track of all the things that we’re doing and trying to make a startup kit of the resources we’ve been using so that the program is…expandable. If we experience success in the Bay Area in our 10-mile radius, there is potential of expanding it throughout different college campuses. If we’re really able to do that, then we’ll actually be able to make a much greater impact.”