It’s a few days before Christmas, and Chris Molak, a senior Economics major at Texas A&M, is preparing for a New Year’s trip to Aruba with his parents. “My brother killed himself on the fourth,” Molak tells me. “So we’re trying to get out of town before that date arrives.”

Chris and I are sitting at a bakery in Alamo Heights, one of San Antonio’s more affluent suburbs. Around us, people sit down to lunch before resuming their Christmas shopping and braving the stifling traffic on Broadway. The holiday atmosphere is palpable, but for Molak, the garland and twinkling lights are a harbinger of a disheartening anniversary for him and his family.

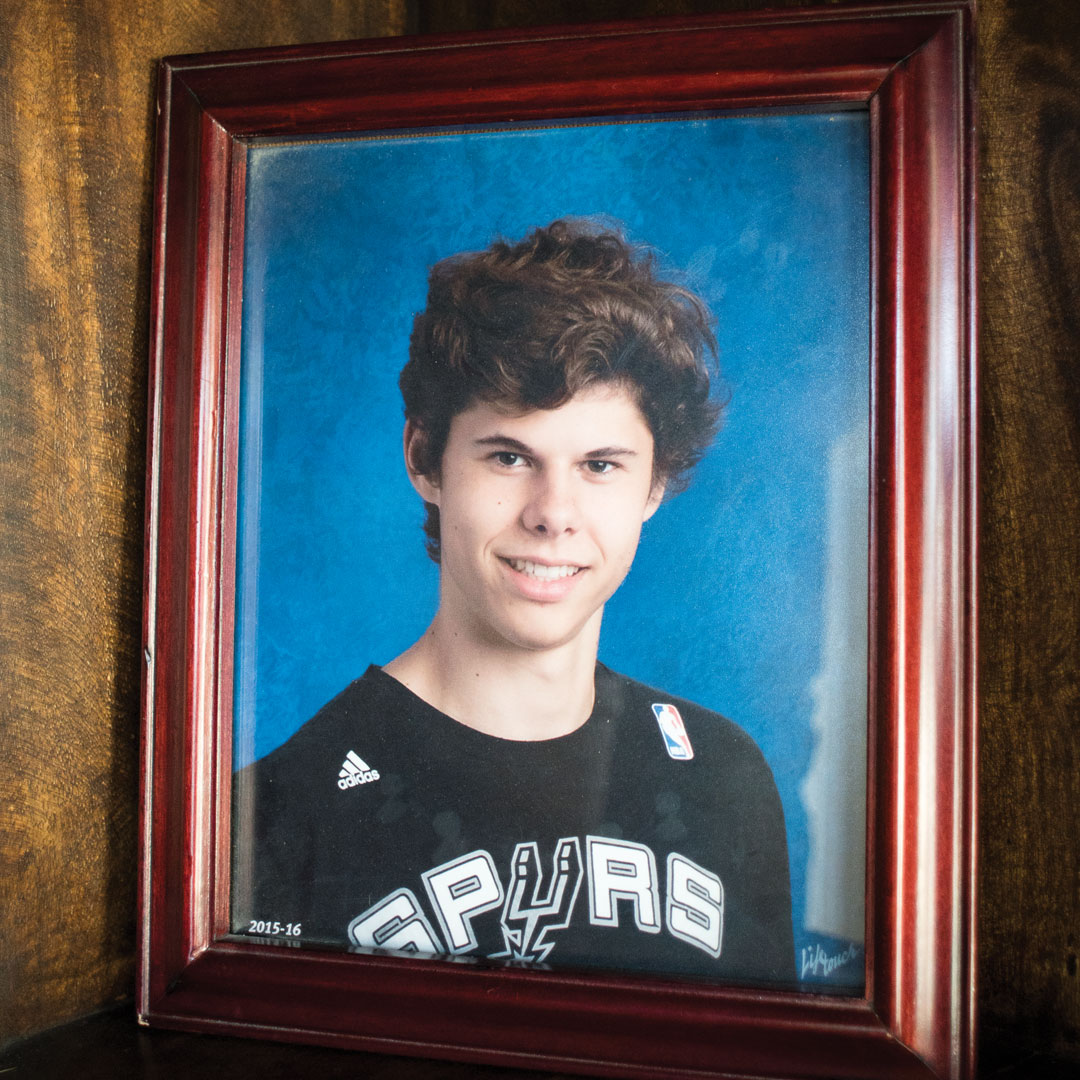

On January 4, 2016, Molak’s sixteen-year-old brother, David, took his own life at his family’s home. Leading up to that night, David had endured months of abuse and torment from his high school cohorts, the majority of which occurred on his social media portals. According to Molak, the bullying began earlier in the year when David’s basketball teammates started targeting him on team bus rides after their games.

“The other kids on the team would rub snot on David to get him to not talk during the ride home from games. He couldn’t fathom why it would happen to him, because he didn’t do anything to provoke it,” says Molak. That lack of provocation was most befuddling; why would anyone select someone like David as a target for ridicule?

David Molak was, as his parents described, a sensitive child since birth. The youngest of three boys, Molak describes David as the typical goofy baby brother. “Mischievous,” he reflects, “but he never, ever thought to inflict harm on anyone.”

The Molaks are avid hunters, and David was just as much a sure shot as anyone else in the family. Putting a bullet in a deer demands a laser-focused level of precision to ensure a quick kill. An inch or two off target, and a hunter can wound the animal, making its last few hours agonizing as it retreats.

For David, this was never an option. “He was a lover, not a fighter,” says Molak. “He empathized with everything that felt pain. The reason he became such a good shot was that he didn’t want to see the animal suffer.”

David’s capacity for mercy, however, would not be shared by others in his community.

The early bullying intensified when David began dating an Alamo Heights girl later that spring. She was considered among the more popular students at school, and the arrangement drew the ire of his classmates, who couldn’t understand how a kid as amiable and effusive as David could score the affections of one of the more attractive and coveted girls in school. “They were bullying him about it, and it eventually led to the IG post,” Molak says.

The abuse and harassment being heaped on David took a more threatening turn when he posted a picture of himself and his girlfriend on Instagram. Almost immediately, his classmates flooded the comments section with messages promising violence (“square up,” one commenter challenged) and potshots taken at his appearance (“Molak’s an ape”). “Put em 6 feet under,” one commenter posted, followed shortly by another similar post reading, “put um inna coffin.”

The now infamous IG post opened the floodgates on what would become a torrent of abuse by way of social media. “People would post things to his Instagram from fake accounts, so that they could easily be deleted and uneasily traced,” says Molak. David was a consummate athlete, spending hours at a local gym called The Tribe, where his work ethic in the weight room earned him Athlete of the Month honors in October 2015. Yet every attempt at bettering himself athletically and academically only garnered him more bullying online.

Distancing himself from Instagram and Facebook provided no respite either, as his tormentors found new ways to come after him. “He started getting added to group chats where numbers he didn’t recognize would slam him and then delete him. [My older brother] and I couldn’t believe that this new technology was being used to destroy people,” says Molak.

By end of the fall semester, David’s abuse had reached critical levels. Alamo Heights was no longer a viable option, so twice his parents transferred him to other area high schools. A change in venue did little to alleviate his victimization; taunts and threats followed him to San Antonio Christian, the last school he’d ever attend. By all accounts, he was in no position to socialize with his new classmates, becoming a shell of his former self. “We just wanted to get him to school the next day,” Molak says. “That was the priority.”

On Sunday, January 3, with school set to resume the following day, it became clear that David had no apparent desire to return. At around 10 p.m. that evening, Molak went into his brother’s room to say good night. David, he recalls, looked up at him with a sort of knowing look in his eye, as if he knew something that his brother did not.

Molak went to bed wary and unsettled, and after wrestling with his concern, went back to check on his brother. He found the bedroom light on, but no sign of David. Immediately, Molak woke his mother, alerting her to David’s sudden absence. They combed every room in the house before taking to the streets, eventually calling the police.

It wasn’t until dawn when they found David in his own backyard. They were mere hours too late.

The Insolence of Office

The machinations of what would become David’s Law were set into motion even before the Molak family was aware of such a bill.

San Antonio high school student Matthew Vasquez was diagnosed with lymphoma in 2014. As he battled one form of cancer, another took form on Twitter and Instagram. An anonymous user created an account with the sole purpose of bullying Vasquez as he was fighting for his life. Among other messages, the user mocked Matthew for simply being ill, and went as far as to encourage suicide. “That someone would use his cancer as a basis for their attacks is just unfathomable,” Vasquez’s father said in an interview with San Antonio’s NBC affiliate, WOAI.

Vasquez went into remission later in the year, but in the interim he faces a three-year treatment protocol. Through it all, the cyberbully who tormented him during the first stages of his treatment continued to make fake Twitter accounts, even as old ones were suspended or shut down.

As of today, Vasquez’s bully has never been identified.

Disgusted by the vileness she saw inflicted on Matthew Vasquez and the obstacles the family faced attempting to end his abuse, Texas State Representative Ina Minjarez decided enough was enough. She sought the aid of Senator Jose Menendez in the drafting of a bill to combat exactly the type of needless cyberbullying Matthew was subjected to.

Based on Grace’s Law, an anti-cyberbullying bill passed in Maryland, Minjarez’s bill would make it a misdemeanor for minors convicted of harassment or bullying via social media. Further, it would strengthen the power of school districts to investigate cyberbullying cases and punish students that were found to be involved.

It was while Minjarez, Menendez and the Vazquez family were synthesizing the tenets of the bill that David’s suicide and subsequent investigation were reported in San Antonio. The loss struck Rep. Minjarez especially hard. Instantly, she knew her bill now had a face. With the efforts of both the Molak and Vasquez families, some honest change seemed imminent.

But, as is so often the case, there exists doubt.

A Multitude of Factors

While David’s Law can be seen as a step toward bringing cyberbullying to an end, the bill and other legislation of its ilk is not without its skeptics.

Attorney Nancy Willard is the the author of “Cyberbullying and Cyberthreats: Responding to the Challenge of Online Social Aggression, Threats, and Distress.” A victim of bullying in her childhood, Willard is at the forefront of research in the topic of online abuse among children and adolescents, and is a frequent commentator on the legality of anti-cyberbullying legislation.

Upon reviewing David’s Law and its antecedents, Willard has found some troubling trends in their presentation and language, beginning with the tradition of naming such laws after victims who have committed suicide. “The problem with this is that it normalizes suicide as a response to bullying,” she tells me via email. “You are telling young people that if they are being bullied, suicide is an option.”

This is not an unfounded concern; the CDC reports that suicide is the third leading cause of death among people age ten to twenty-four. In addition, the CDC also recommends against framing bullying as a singular cause of suicide, alleging that doing so could encourage copycats, and that it devalues the multitude of factors that contribute to a person’s decision to take their own life.

This latter point informs a constitutional snafu that David’s Law could face if brought up in court. I’m not talking about how opponents of anti-cyberbullying legislation cite the first amendment as a defense against the law’s constitutionality. That’s nonsense. As most any politician will tell you, the right to belittle and harass people online is no more protected under the free speech amendment than the right to shout “Fire!” in a crowded cinema or phone in a bomb threat to a baseball stadium. Freedom of speech does not include freedom to harm.

The issue Willard has cornered is the numerous factors that contribute to suicide. Outside stressors, personal affect and other traumas can be pinned as risk factors. “Any competent professional in the field of suicide prevention will tell you that it will be impossible to establish whether a [bully’s] conduct has caused someone to commit suicide.”

A Toxic Environment

All those factors considered, there’s one angle to the narrative that might help explain the plight suffered by youngsters like David Molak. It could be argued that the cyberbullying that David suffered was due in part to the perceived cliquey and privileged attitude of some of the students in his affluent neighborhood and school.

Chris Molak is hard-pressed to disagree: “There is a culture issue, a status hierarchy. Because [Alamo Heights residents] have had comfortable lifestyles for so long, some of them believe they can just look down at other people.”

The thing about social status is that it’s not a self-sustaining entity. Economic status, sure. But social esteem wallows in the paranoia that it might one day disappear. Those who possess it are in constant need of reinforcing its influence for fear that it will diminish. For wealthy, popular students, an easy way of accomplishing this is by picking on others who they view as lesser individuals.

How do bullies like the ones who assailed David Molak manage to fly under the radar of educators and law enforcement? It all stems from our preconceived interpretation of the archetypal bully. The psychological profile assigned to most bullies includes such predictors as delinquent tendencies, poor academic performance, drug/alcohol usage, sexual promiscuity and an abusive home life. The media and Hollywood do their part to shape and reaffirm this stereotype, where bullies are steadily portrayed as lowbrow thugs with poor vocabularies and poorer social skills.

This definition isn’t enough, and it doesn’t adequately explain why David Molak became a target. But as to why these types of bullies avoid punitive actions? Nancy Willard has an idea: “Educators rarely pay attention to these socially dominant students because they are compliant, socially skilled and have powerful parents who would object to any discipline.”

Where does this leave us?

A Change in the Heart

With legal complications abounding and an education system that mostly has its hands tied, the fight against cyberbullying at times feels like being trapped in a flooding cellar, as more problems arise before solutions can be conceived. Yet, through it all, one solution can be firmly agreed on: We need to be better to each other.

Nancy Willard believes a change in attitude in the schools is the place to start. “A focus on a school climate that empowers students to foster positive relations and to respond effectively in hurtful situations—when targeted, being hurtful or as a witness,” says Willard.

“We shouldn’t be teaching the sensitive people to change, we should be teaching the more vicious people to be more sensitive,” Molak laments. “We should be teaching respect and compassion. Retaliation against a bully may work for some people, but for sensitive, lover-not-fighter kids like David, it’s not an option.”

The Texas State Congress convened on January 10 of this year. It’s at this meeting that David’s Law was brought to a vote. According to Rep. Minjarez, we’ll know if David’s Law will go into effect by May. She’s confident, citing support from House Speaker Joe Straus, but she’s not taking anything for granted.

For the Molak family, what becomes of the bill named after their departed child is now out of their hands. But Molak is still optimistic about the future of his hometown.

“It’s nice to see the signs and Facebook posts and videos and whatnot. But what I’d like to see most is change. Change in the hearts of the community itself.”

[…] MORE >>> […]