Healthcare has been an intense debate in American politics over the last several years. With Republicans’ three (failed) attempts to repeal and replace Obamacare in the last nine months, healthcare could be considered one of the biggest ongoing political debates nowadays.

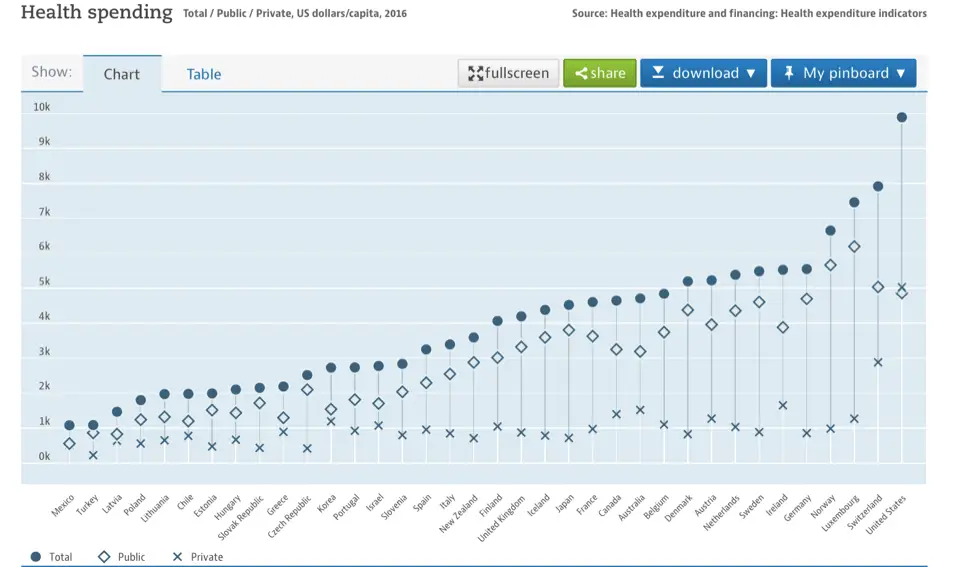

Today, America’s current healthcare system can best be described as a hybrid system. America doesn’t opt for a national, or universal, health system, nor a multi-payer or single-payer system, but rather a strange mixture. In 2015, 48 percent of health care spending is from private funds, such as a private business or individual households, while federal government contributed 29 percent and state and local governments were responsible for 17 percent. With this unbalanced distribution of spending, the United States pays more per capita, or per person, for health care than any other developed countries in the world, including those with a universal healthcare system such as Canada or the United Kingdom. This makes spending on healthcare a whopping 17 percent of America’s GDP compared to the 9 percent of GDP Australia dedicated to its universal healthcare system.

And, clearly, this system isn’t the most beneficial. With twenty-eight million Americans uninsured, as of 2016, under the Affordable Care Act, a.k.a. Obamacare, a number that has decreased significantly over the last decade, we still have a high uninsured rate at 11.7% as of the second quarter of 2017. With such high spending and large number of uninsured people, you’d think those who can afford insurance must be getting some of the best healthcare around, right?

Wrong.

The U.S healthcare systems ranks 28th in the world in quality. The Commonwealth Fund, a foundation that advocates high performing health care systems, has also done several surveys since 2004 in which they compare health care in the U.S and ten other counties—the United Kingdom, Australia, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, Canada, and France—and every time the U.S. ranked last.

So, one might ask, what is the solution to all of these problems?

Well, that’s a rather broad question.

Okay, what about: are there any possible solutions that may alleviate some of these problems?

Better.

And in fact, there is one. While I am by no means a healthcare policy expert, the facts don’t lie, and I certainly don’t base my opinion on false facts. I would argue that a universal health coverage would be one way to solve this current, rather messy, healthcare situation. It’s not the perfect solution, if only there was one, but I believe it will provide enough benefits to American citizens that would make it much better than the current system.

According to the World Health Organization, or WHO, “Universal health coverage (UHC) means that all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.” While this quote is a bit heavy handed, it definitely sounds like something that is too good to be true. As a person of low socioeconomic status, if I could have access to health care without fear of financial consequences, it would be a dream. And I’m sure many other people feel this way as well.

And, as if the previous statistics weren’t enough to make one wary of America’s healthcare systems, the U.S. is the only developed nation to not offer universal health coverage to its citizen. While there are many reasons as to why this is the case, I’m going to make the argument of why it shouldn’t be the case anymore.

Universal health coverage would be beneficial in numerous ways. The first, and probably most important, influential factor is cost. The OECD has shown that countries that offer universal healthcare, such as The United Kingdom, pay significantly less than the U.S. does.

Despite lack of any universal plan, our government spends significantly more in public funds, such as Medicare and Medicaid. So, to sum up, the United States pays more for health care in the public sector, despite not having universal health coverage, than those who do have universal health coverage, yet its citizens receive extremely less, both in quantity and quality, healthcare service.

That’s messed up.

Universal health coverage would change this though. With the only source of health insurance being the government, this system would allow for more negotiations with insurance providers, and consequently a drop in price. John Green explores this idea in his video “Why Are American Health Care Costs So High?” and describes how negotiating would hypothetically play out in another country:

“In the UK, the government goes out to all the people who make artificial hips and says ‘One of you is going to get to make a crap ton of fake hips for everybody who is covered by the NHS here in the United Kingdom. But you better make sure your hips are safe, and you better make sure that they are cheap, because otherwise we’re going to give our business to a different company’. And then all the fake hip companies are motivated to offer really low prices because it’s a really huge contract.”

Another reason why universal healthcare system benefits Americans concerns moral reasoning. Many argue that health care is a human right, not a privilege. Due to the privilege in American healthcare, many of the uninsured, and even insured ones with low-income status, are needlessly suffering, or even dying merely because they cannot afford the help they need. This shouldn’t be the case. Everyone deserves equal right to healthcare. No one should have to lose their child, a loved one, or even their own life to an illness because costs were too much for them to cover, sometimes even with insurance.

One key advocate of this moral reasoning, Bernie Sanders, has been arguing for universal health coverage and recently made a big step forward in his mission for better healthcare with his plan called “Medicare for All.” And while Sanders was realistic enough to predict the failure of this bill to pass under a House and Senate controlled by the Republican, he knew it was important to begin the conversation for the Democrats. When Sanders tried to introduce something similar in 2013, he had zero co-sponsors, but “Medicare for All” now has sixteen co-sponsors, including Senator Elizabeth Warren.

While I feel like in the past week that I have done enough research to make me a healthcare policy expert, I am still not. However, I am an advocate for equal healthcare access for all, and I can only hope that the conversation will continue to be pushed forward, just as Sanders’ bill has been, and that someday all Americans will be covered equally and fairly.