The Case for Doping

If the Olympics are going to ban PEDs, why should they not ban all performance enhancers?

By Tim Philbin, College of the Holy Cross

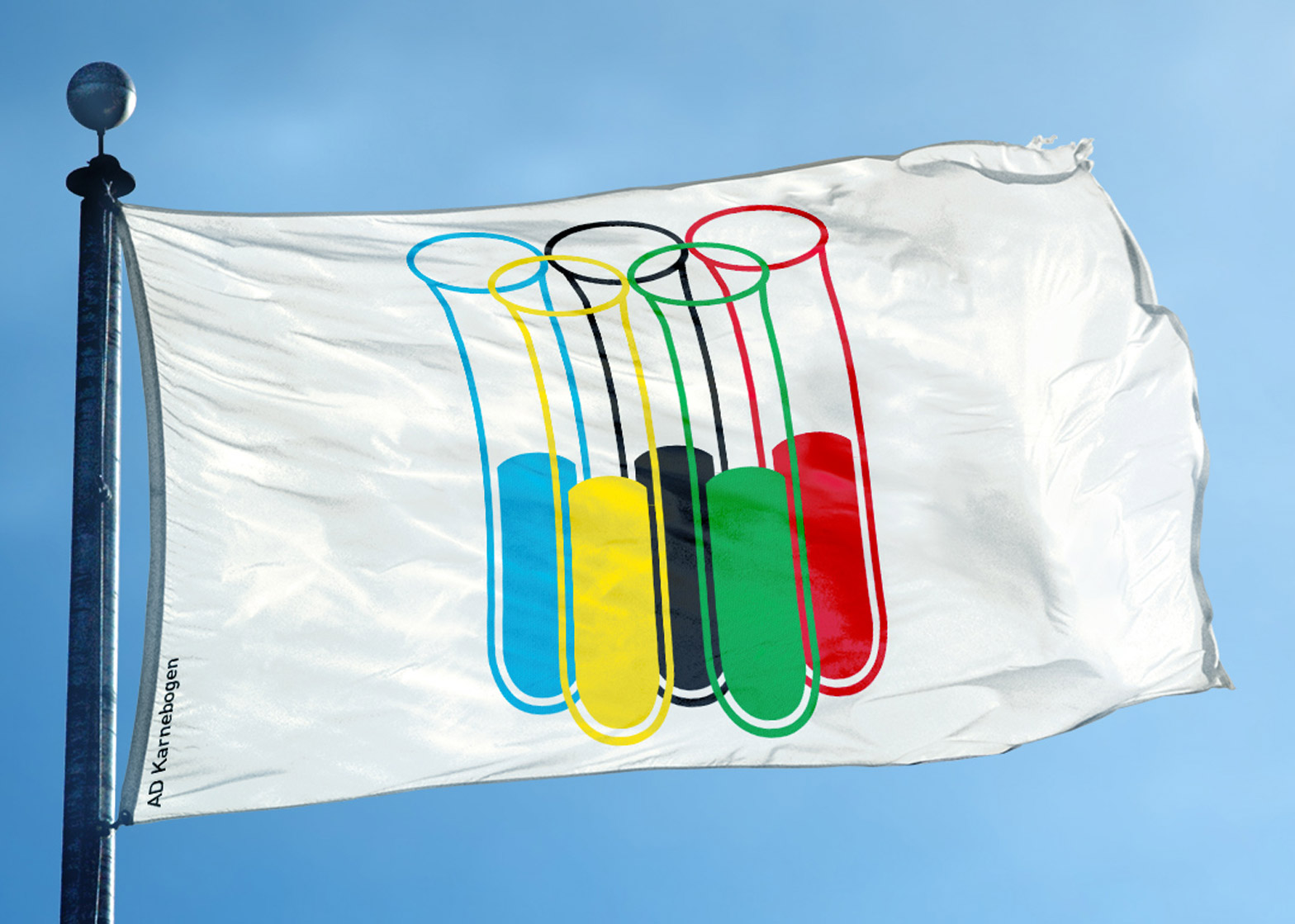

In the past few weeks, the world has been scandalized to hear that Russian athletes took drugs to artificially enhance their performance.

Various talking heads took turns excoriating Russian Olympic athletes for doing something so patently unfair. The Olympic committee itself has been fairly unforgiving in its criticism as well, even toying with the idea of a blanket ban for all Russian athletes.

Though they eventually backed off from such a draconian punishment, everyone seems to agree that the Russians’ use of performance enhancing drugs is just plain unsportsmanlike. After all, the Olympics should be about establishing an even playing field to determine who is truly the best athlete, not who took the most drugs, right?

Though they eventually backed off from such a draconian punishment, everyone seems to agree that the Russians’ use of performance enhancing drugs is just plain unsportsmanlike. After all, the Olympics should be about establishing an even playing field to determine who is truly the best athlete, not who took the most drugs, right?

There is something about doping that seems fundamentally at odds with the spirit of fairness that dominates amateur athletics. On the surface it just feels like a shortcut; where everyone else put in the long hard hours of grueling labor to achieve peak levels of performance, the cheaters who didn’t want to do all of that hard work bypassed that long and arduous process by simply swallowing a pill or receiving an injection.

Then at the end of the competition, those dastardly villains who unfairly enhanced their performance profit from their evildoing and stand up on the platform to receive their gold medal with their national anthem playing, while honest hard working athletes who tried their best are forced to watch from the stands and wonder how they could’ve done better.

This sense that enhancing one’s performance by such artificial means is fundamentally unfair is the reason that doping is illegal. But there are some questions that occur to me about the validity of this line of thinking; after all, it seems to me that the Olympic committee allows athletes to profit from other advantages that they did not work for.

Take Michael Phelps for example. Phelps is one of the fastest swimmers in recorded history. He holds world records in the 100m butterfly, the 200m butterfly, and the 4x100m freestyle. Of course Phelps has put in countless hours of hard practice, but he brings unearned advantages to the table as well.

First of all, Phelps’ body is perfect for swimming. He is 6 feet 4 inches tall, but his wingspan is 6 feet 7 inches. A normally proportioned person’s wingspan is roughly equivalent to their height, but Phelps’ long arms help him push himself through the water when he swims the butterfly.

He has double jointed knees and ankles and size 14 feet. This hyperflexibility allows him to whip his feet like flippers when he kicks. Phelps has an incredibly long torso; even though he is 6’4,” he has a 30 inch inseam. By comparison, as a fairly normally proportioned male, I am 6’1” and have a 34 inch inseam. Phelps’ relatively short legs reduce his drag in the water, allowing him to swim even faster.

He has double jointed knees and ankles and size 14 feet. This hyperflexibility allows him to whip his feet like flippers when he kicks. Phelps has an incredibly long torso; even though he is 6’4,” he has a 30 inch inseam. By comparison, as a fairly normally proportioned male, I am 6’1” and have a 34 inch inseam. Phelps’ relatively short legs reduce his drag in the water, allowing him to swim even faster.

As if that wasn’t enough, he produces far less lactic acid than the average person. Lactic acid is the agent in the body the produces muscular fatigue. The burning sensation you feel in your muscles after extreme exertion is the result of lactic acid buildup. After a world record performance in the 100m fly, the lactate levels in Phelps’ blood were measured at 5.6 millimoles, about half of the average amount found in other elite swimmers, nevermind the average non-athletic person.

These are all advantages that Phelps enjoys every time he gets in the pool, and he has not done a single bit of work for any of them. This is not to say that Phelps has not put in hours upon hours in the pool physically conditioning himself and perfecting his technique, and for that he deserves all the credit in the world, but somehow I doubt that he would be the most decorated Olympic athlete of all time without this host of genetic advantages.

Furthermore, as an American, Phelps comes from one of the most affluent countries in the world. There is hardly a city in the United States where one cannot find a standard Olympic size pool. Most American children learn how to swim at some point. Even if you don’t realize it, that’s a massive competitive advantage in the Olympics. If you don’t believe me, then watch this story about Yusra Mardini, a Syrian refugee who is swimming in this year’s Olympics for the refugee team. Syria is an impoverished war torn nation, one where swimming is not very high on the priorities list. The best training Mardini got before she got to Berlin was dragging an overcrowded sinking boat through the Mediterranean Sea for three hours on her way to Turkey.

Unfortunately, it almost doesn’t matter how much Mardini practices; she will still be at a significant competitive disadvantage. Simply because of the simple fact that she was born in the wrong part of the world, her performance as a swimmer will be diminished.

The fact is that Olympic competition is not now and never has been fair.

Fairness in world-class athletic competition is a complete and utter illusion. A whole host of factors out of the control of athletes control their performance: country of origin, affluence and genetics all play a role. Fairness is a kind of romantic illusion that surrounds amateur sports, but it does not now nor has it ever actually existed.

Therefore the way the rules are configured right now is completely self-contradictory. On the one hand, the Olympic committee excoriates Russian athletes for doping to achieve an unfair advantage, but on the other hand completely ignores the other ways in which Olympic competition is completely unfair.

In my view, they need to go one of two directions; either they must allow doping and accept unfairness in athletic competition as inherent, or they must ban doping but attempt to eliminate unfairness in athletic competition entirely. It almost doesn’t matter to me which way they go, but this denial of unpleasant realities cannot continue.