The Confusing State of Patriotism in America

In the midst of volatile politics and shifting international dynamics, the meaning of patriotism has become murkier than ever before.

By Andrew Mikula, Bates College

I recently took a spin around my hometown to tackle a short list of errands.

I got a haircut, picked up my sister after her practice ACT (stirring up some cringe-worthy memories in the process) and stopped by the bank. For amusement, I decided to count how many American flags I saw during the trip. I was in the car for about 30 minutes total, yet I saw 36 star-spangled banners. They’re everywhere: outside of post offices, schools and libraries, attached to streetlamps and overpasses and hanging next to people’s houses. I also saw a “proud to be an American” bumper sticker and a couple of pedestrians wearing U.S.A.-themed t-shirts. And I took this trip a couple of weeks before Independence Day.

These bountiful and sometimes elaborate shows of advocacy for one’s country and its associated values constitute the very definition of patriotism. It’s natural to feel sentimental about one’s home nation, and America is considered one of the most patriotic nations in the world by several different sources.

The United States as a whole has a generations-long legacy of a particular breed of nationalism, which often comes with a sort of implied superiority, language claiming that America is the “greatest nation in the world” and similar dialect. Such dialect is largely spurred on by politicians who use it to appeal to voters or, alternatively, deride their opponents as unpatriotic.

The United States as a whole has a generations-long legacy of a particular breed of nationalism, which often comes with a sort of implied superiority, language claiming that America is the “greatest nation in the world” and similar dialect. Such dialect is largely spurred on by politicians who use it to appeal to voters or, alternatively, deride their opponents as unpatriotic.

However, perhaps this form of patriotism is a corruption of what it originally meant to be patriotic during America’s early history. During the Revolutionary War, a “patriot” was anyone who wanted independence from Britain. Because many Loyalists fled the newly formed country after the war, the majority of early Americans were by definition patriots. Most early Americans were also united by their terrible dental hygiene. However, these “patriots” didn’t necessarily have the same sense of devotion and belongingness to the United States that many Americans have today. The Articles of Confederation, the document initially establishing the former colonies as politically united, was extremely weak and short-lived. Rebellion against the ineptitude of both state and federal governments threatened the structure of the young nation. Until 1791, the U.S.A. didn’t even have a central bank.

Instead, what united the early patriots against the rest of the world was their political ideology. In seeking their independence, they were champions of individual rights and representative government in an era defined by monarchy and oppression. At the time of the U.S. Constitution’s adoption, for example, the Netherlands was perhaps the only other country that constitutionally provided freedom of religion.

Today freedom of religion is a basic right enjoyed by at least 132 countries, not something that makes America unique. And no one is pretending that political ideology is something most Americans have in common. Today, there is extreme political polarization and deep-seated partisan antagonism in the United States. In such an atmosphere, patriotism has increasingly been seen as belonging to the Republican Party only, and perhaps the principal legacy of the 18th-century patriot is a football team. Today, patriots are more likely to be associated with the Deep South than with colonial New England. But why?

Over time, the tone of patriotism has changed in America. Today, many people even equate the United States’ accomplishments with their own, as implied by the phrase “proud to be American,” which is undoubtedly a pervasive statement. A Facebook page of the same name has almost 5 million likes.

Yet love of one’s country is assuredly different than “pride.” According to Vocabulary.com, pride is defined as “a feeling of happiness that comes from achieving something.” But being an American isn’t something that natural citizens have achieved, and to assume it is seems pretentious and conceited. Most Americans are American because they’re born here, and it’s clearly controversial to be “proud” of other traits that are inborn (I wouldn’t consider myself proud to be white or proud to be male), so why is it considered okay—and maybe even song title-worthy—to be “proud to be American”? Perhaps it’s because the United States is such a deeply ingrained part of people’s identities that they associate the accomplishments of long-dead Americans with all Americans, past and present. This sentiment has, in modern times, been seen as an embodiment of patriotism.

But for the nation’s Founding Fathers, patriotism was less about shared achievement and more about shared beliefs.

For them, the solidarity of patriotism as a concept depended on what it is patriotism resists. In the 18th century, patriots were against the British monarchy. Their ideas were then associated with classical liberalism, a movement that formed the basis for America’s founding. However, more recently, patriotism has been employed to resist phenomena typically opposed more strongly by conservatives, such as globalism, terrorism and illegal immigration, which probably helps explain why more Republicans than Democrats consider themselves patriotic today.

And there are other demographic associations people have with patriotism. Older people also tend to be more patriotic, partly because younger generations shy away from institutionalism, as this article explains. However, this notion also might imply they tend to embrace individuality and other traditional American values. Millennials have a bit of a unique relationship with patriotism, having come of age in a highly interconnected social media landscape simultaneously wrestling with perpetual large-scale terror attacks and international conflict. The former wants to shield the world under one umbrella. The latter creates a downpour of fear and contempt for other countries, international migrants and even religious groups.

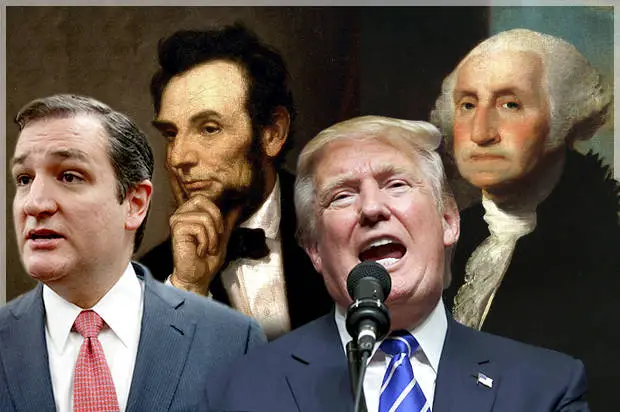

For the past year or so, one voice has brought a brand of patriotism aimed at combatting globalism bubbling to the surface. And that voice is scratchy, outspoken and heavily New York-accented.

In a campaign dominated largely by inconsistencies, Donald Trump has remained relatively steady in his position on perhaps only two core issues: international trade and illegal immigration. Both of these issues in turn reflect a distrust of globalism, which Trump has artfully labeled as “a false song.” His “America-first” foreign policy reflects a new, urgent sense of nationalism stemming from disdain regarding President Obama’s trade deals and diplomacy, which are often seen as weak and overly compromised. The result is a brand of patriotism that—unlike any arrogant sense of pride—truly reflects populist anger, a scary prospect for Trump’s main political opponent. This grassroots nationalism is exactly the same kind that swept up the nation in the early 1770s. If you think Donald Trump has little chance of being president come January, you might be wrong.

In a campaign dominated largely by inconsistencies, Donald Trump has remained relatively steady in his position on perhaps only two core issues: international trade and illegal immigration. Both of these issues in turn reflect a distrust of globalism, which Trump has artfully labeled as “a false song.” His “America-first” foreign policy reflects a new, urgent sense of nationalism stemming from disdain regarding President Obama’s trade deals and diplomacy, which are often seen as weak and overly compromised. The result is a brand of patriotism that—unlike any arrogant sense of pride—truly reflects populist anger, a scary prospect for Trump’s main political opponent. This grassroots nationalism is exactly the same kind that swept up the nation in the early 1770s. If you think Donald Trump has little chance of being president come January, you might be wrong.

Some sources say this election cycle is encouraging a decline in patriotism when widely disliked candidates do so well. Perhaps others see how Trump is using nationalism to speak out against immigrants and minority groups and distance themselves from patriotism further. However, young people have simultaneously reaffirmed the original purpose of patriotism: to support the guiding principles of individualism and equality on which the country was founded. This past primary season, they overwhelming favored another populist candidate, one on the opposite side of the political spectrum as Donald Trump. And Bernie Sanders has a kind of grassroots patriotism of his own. Sanders’ supporters have rallied around defeating not monarchical injustices but economic ones.

Patriotism in America stands at a crossroads. While mainstream politicians continue to employ pride to win elections, Donald Trump is creating a new role for nationalism in the United States. Otherwise, younger generations will probably continue to reflect a nationwide decline in patriotism over the last decade, even while they embody the Founders’ virtues with their lifestyle choices and endless aim of justice.

The condition of patriotism today reflects the state of polarized national politics: patriotism is either about pride and devotion, rebellion and unity, or blindly practicing traditional values, depending on who you look at. But patriotism doesn’t have to be arrogant or angry. It can also be about love and thankfulness.

I don’t know many people who took their precious day off from work to go rant about politics online. I also don’t know many people who spend their Fourth of July holidays trying to dissect what the Founding Fathers thought patriotism was (okay, I’m kind of a hypocrite on that one). But I do know people who spent time with their families. They didn’t even think about terrorism or trade policies. They felt safe enough—lucky enough—to take the time to decide between putting ketchup or mustard on their hotdogs.