The image of the gay pride parade is a familiar one. Rainbow flags come to mind. Unbelievably fit men in shiny, skimpy underwear dancing on parade floats are inevitable. Glitter abounds, thrown up to the sky with joyous abandon; people smear it across their smiling faces while having the time of their lives.

And of course, flecks of the shimmering stuff remain glued to every possible surface for days on end as an ineluctable memory of the festivities. In short, gay pride parades promise endless fun and they sure as hell deliver.

For a population that has seen some of the worst discrimination has to offer, pride may be a justified celebration of survival. And for a group that has worked doggedly to reverse public opinion in an incredibly brief period of time, a mindlessly giddy parade would seem like a hard-won reward.

However, when one in five transgender people have experienced homelessness, most states still don’t offer unequivocal legal protection for LGBTQ-identified individuals and many people in the LGBTQ community bristle at the prospect of adding black and brown stripes to the pride flag to express solidarity with queer people of color, one begins to wonder what the glitter actually means.

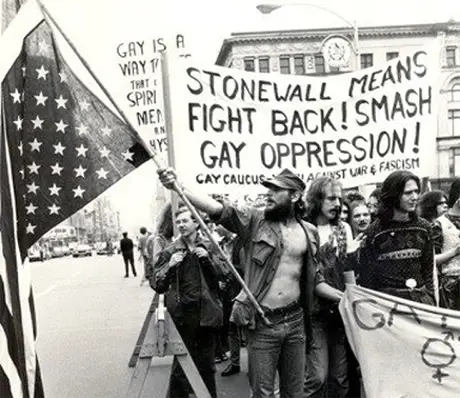

After all, the roots of the gay rights movement in America are far from glittery. For years, the idea of gay rights only existed in the margins, in the shadows, in the sweaty, grimy underground. The LGBTQ community only came into light in 1969, when police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City, unleashing centuries of pent-up rage.

It’s strange to think that the original celebration of LGBTQ identities took the shape of riots and protests led by drag queens and transgender people of color, considering who one normally sees at the helm of pride parades today. Still, the fury released during the Stonewall riots continued throughout the ’70s.

The world’s first pride parade took place in Chicago in the summer of 1970. Signs reading “gay liberation” and “gay freedom” stood as precursors to “gay pride,” the curiously stripped-down modern version. For LGBTQ activists in the 1970s, securing political rights and social recognition required radical means; if that meant smashing a pie in Anita Bryant’s face on live television, so be it.

The turn from “gay liberation” to “gay pride” didn’t happen until the ’80s; after the scourge of the AIDS epidemic, people were just too tired to muster up that same fury. Pride served as a memorial for the thousands lost to the fatal disease.

In addition, pride became an affirmation of the living, who, of course, took pride in who they were. But the rush to reinvent the gay rights movement exposed a series of fault lines within it.

Gay pride raised tensions between those who identify as LGBT and those who call themselves queer. The former see the term “queer” as an ancient slur best left to history; the latter perceive “LGBT” spaces as only nominally inclusive when, in reality, they belong mostly to white cisgender gay men.

To many queer-identified people, entering an “LGBT” space means checking certain identities at the door. Even worse, it may mean that there is no place for you there.

This divide has been around since the beginning of the movement. Despite its radical nature, the gay rights movement of the ’60s and ’70s were mostly composed of white male homosexual voices. Lesbian voices, bisexual voices, trans voices and black and brown voices seldom found the way into spotlight.

Having been marginalized inside an already heavily marginalized group, these sidelined voices found solace in establishing queer spaces, where they could have discussions of race, class and gender in tandem with discussions of sexuality.

What resulted, unfortunately, was a stark divide between the two factions. Even today, if you look up resources for queer students on college campuses, you are bound to find two distinct organizations: one explicitly LGBTQ-identified and one explicitly queer-identified (usually designated for queer and trans people of color).

The LGBTQ movement has made huge advancements over the past few decades; still, no amount of glitter can sugarcoat the hard realities of living in the queer community, especially in today’s turbulent political climate.

Violence against trans and gender non-conforming people is on the rise, Islamophobia and xenophobia are driving LGBT voters to the far right and queer refugees fleeing crises in the Middle East are finding themselves in yet more dire straits upon reaching supposedly safer shores.

In addition, while the gay rights movement may have started in a seedy bar in Greenwich Village during the late ’50s, since then it has taken on a global dimension.

The modern LGBTQ community encompasses millions of diverse individuals around the world. All of those people deserve more attention in the Western-centric gay pride parades which tend to ignore them.

However, there is some hope that times are changing: just this past week, Stonewall, the United Kingdom’s largest LGBTQ organization, withdrew support of London’s annual Pride parade over concerns of a lack of representation in favor of UK Black Pride, a collective dedicated to raising up queer voices of color.

Maybe other LGBTQ groups around the world can follow Stonewall’s example and show support for the queer community.

Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong about the glittery ecstasies of gay pride parades. People do deserve to let go and escape the problems hounding them on a daily basis. But in these times, when the progress that activists worked so arduously to make is threatened, pride parades must center political action as they once did.

In addition, when the queer community has expanded so far beyond the scope of the Stonewall Inn Riot, they must also center voices they have historically excluded. Justice reserved for the privileged few is still injustice; gay pride parades should recognize the intersectionality of their constituency.

Police brutality against African Americans is as much a gay rights issue as it is a black rights issue. Access to mental health resources concerns the LGBTQ community as much as it does the disabled community.

Racism, classism and sexism all fall under the purview of gay rights, though it may not always seem that way. In this new age of political instability, it will no longer suffice to glitter and be gay; it is time to persist and be queer.