Student Protestors are Protesting to the Wrong People:

Because if the Quakers got one thing right, it’s conflict resolution

By Ty Joplin, Haverford College

I go to Haverford College, a tiny liberal arts school. Originally established as a Quaker school, students are given an astounding level of autonomy—we made our own alcohol policy, have no RAs or faculty bunking with students in dorm buildings, and we administer our own student-written honor code that covers both academic and social life.

If a student violates the social part of the honor code that stresses accepting each other’s identity without prejudice, they are confronted by another student, and the two talk it out. Essentially at Haverford if you see something, say something.

Most of the time, the confrontation looks more like a conversation. The confronting party explains the harm in the other student’s actions and attitudes. If this conversation doesn’t work, students are encouraged to contact the Honor Council, where a neutral student will mediate the conversation through to the end.

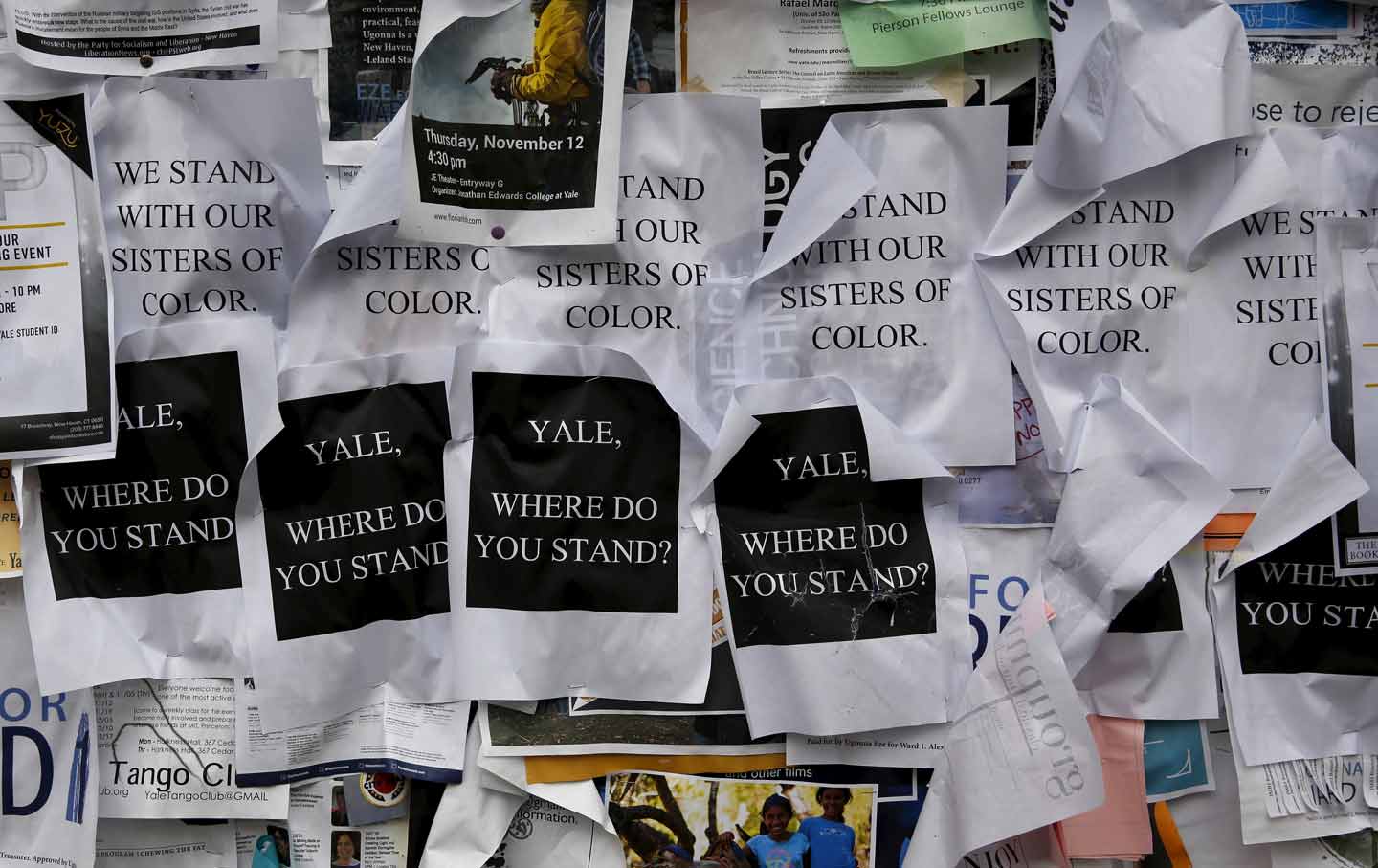

Places like Mizzou, Yale, or Ithaca College, where student protestors are demanding stronger responses from their administrations to campus-wide racism, don’t have the same social culture as Haverford.

A Yale fraternity recently hosted ‘white girls only party.’ If that happened at Haverford we would expect the administration to deem that inappropriate. But we wouldn’t be satisfied with that.

We wouldn’t trust the administration, with all of its red tape, slow-moving bureaucracy and considerations of irrelevant things like bad press, to respond in a way that captures our discontent at the event. We would confront those who hosted the party—sit them down and talk with them about it until they understood.

Students around the nation responding to prejudice should, of course, confront unresponsive administrations, but they should spend much more time and energy in directly confronting those prejudiced individuals and groups on campus.

Conduct sit-ins in their frat houses, invite them to mediated discussions—protest their actions to them. It is surprisingly counterintuitive to bear witness to racism on campus and, instead of confronting that racism, then confront the university administration, expecting them to be the main crusader against such prejudices.

Theoretically, since they have more disciplinary tools at their disposal than student groups, school administrations are the most equipped to handle campus-wide instances of racism. But relegating responsibility to the administration often invites heavy-handed actions that emphasize discipline, which can lead students to hide and repress racism rather than have it rooted out by addressing the core moral issues.

Action from on high censures rather than encourages genuine progress, in addition to infantilizing the power of student protestors and degrading the powerful voice groups can bring to bear in confronting their peers.

It also hands over well-articulated student grievances to a third party that has so far, on many campuses, failed to show much initiative in developing adequate action plans to take care of the problems.

Rather than intensify pressure on the administrations to act or send the right condemnatory email to the right people, students should take back their grievances and direct them to the perpetrators themselves.

This approach doesn’t work easily with big universities where there are many students and voices. In these spaces, it may seem like the only feasibly way to cut through the saturation of opinions is by trusting the over-arching administration to take decisive action.

But if this student-empowered culture doesn’t exist on these campuses, students need to create it. An unresponsive administration is a great opportunity for students to root out social problems on campus by confronting those who act unethically and marginalize others. After all, it is the student protestors who often have the most precise diagnosis of the problem, since they are the ones living with it and suffering through it.

A few years ago at Haverford, some students dressed up as caricatured black women for a Halloween party, the same type of party that has become a national ground zero for prejudice. These students were confronted.

The confrontation went to a mediated discussion, and those students were made aware of their unethical behavior while gaining insight from their peers about how they need to change.

The same social structures to facilitate this discussion may not exist at other universities, so students need to make them.

Developing a way to productively engage with instances of prejudiced behavior is not easy by any accounts, as evinced by university administrations’ struggles and blunders for the past two-hundred or so years. But this doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done.

If students continue to defer to bloated and sluggish administrative bodies to root out problems of prejudice, they will be effectively handing over their power and will be forced to wait while only being able to put tangential pressure on the problem through protests against administrations. Rather than entrusting the administration to take action, students should empower themselves to do so, with or without administrative support.