Before the pandemic, I didn’t have much interest in historical fiction — everyday realistic fiction set in or around the present day has always been more my speed. But over the past five months, my definition of “everyday” has changed drastically. And so has my literary taste.

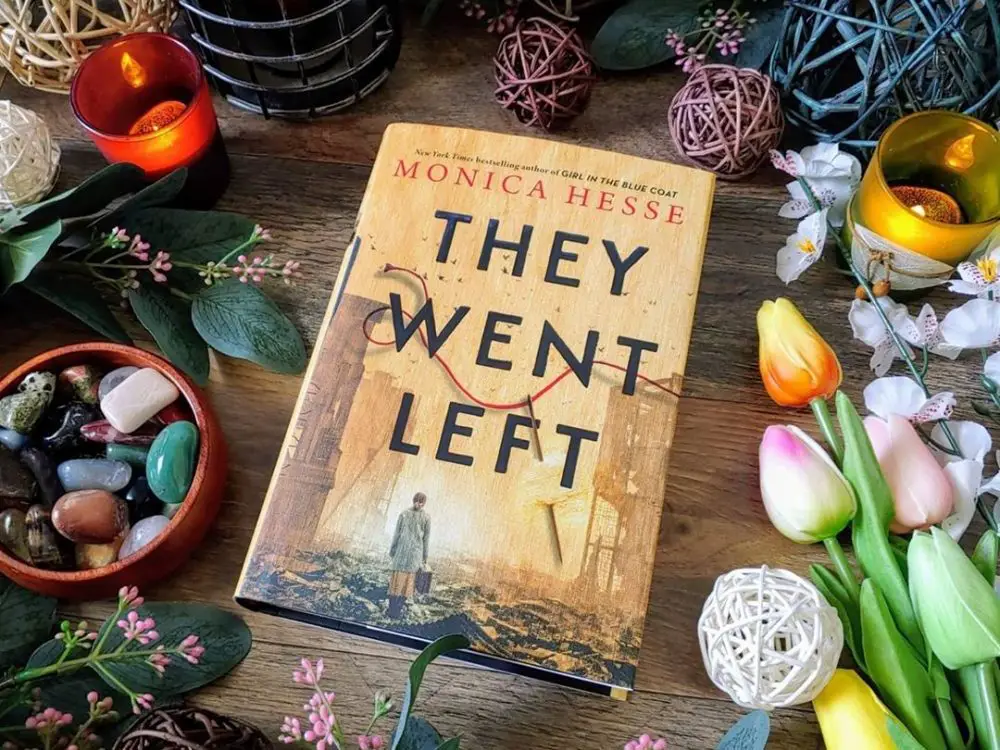

Within the first few pages of “They Went Left,” I realized just how timely the post-war novel was for a world waist-deep in a pandemic.

Experts say that various coronaviruses will probably plague us for years to come. That leaves us smack dab in the middle of a weird, prolonged aftermath with a crisis that’s still raging on. Quarantine fatigue is setting in, America’s mental health issues have worsened and everyone’s uncertain about what the future holds.

But history reminds us that this last problem was present in every war, every genocide, every crisis that has ever come before. People living through hardship didn’t know when, or if, it would end. Like so many of us, they made a half-serious master list of all the things they’d do after it was over. But they could never totally predict how different life would be on the other side.

All things considered, the difficulty of constructing a new life in a post-war world may be remarkably relatable right now. While reading “They Went Left,” I felt an empathy for the protagonists’ mingled hope and pain in a way that would never have been possible if not for the pandemic.

“They Went Left” is the third of Monica Hesse’s historical fiction novels. Each abounds with accuracy and well-researched details, and the last novel is no different. Enriched by written and oral histories of World War II refugees, the book offers lots of insight into the daily struggles of displaced persons that the privileged majority would never need to think twice about. Let’s just say it’s an eye-opening story.

Summary

The book is the story of Zofia, an orphaned Jewish girl who’s trying to find her brother in a post-World War II, Nazi-ravaged Germany. Having lost her parents at a German camp during the war, Zofia is left with no family and an unstable mind after the war is over. She barely escaped with her life, and the end of the war finds her in a hospital for self-described “nothing-girls” whose trauma has rendered their memories unreliable.

There’s one thing that gets her out of bed and out of the hospital: reuniting with her brother, Abek. The only problem is that she has no idea where he is or how to find him. So, with only a few clothes and a scant lead, she sets off on a journey to an unknown place.

Zofia’s search eventually brings her to a rehabilitation camp for various displaced persons. Although Abek isn’t there, she continues to search. Among the myriad people she encounters, she finds unexpected favors and compassionate friends but also cowardly traitors and prejudiced onlookers.

But even though marks of sorrow still dot the landscape, Zofia finds that as she embraces the friendships she builds along the way, she’s freed to move forward into a new life while still honoring her past.

Grappling With a Different You

Hesse doesn’t hesitate to dive into a prominent experience of many refugees: loss. The experience of having a loved one ripped away from you or seeing someone die before your eyes leaves its mark: It forces you to grow up faster than anything else.

From debilitating PTSD to the struggle of operating a changed body to the fears and prejudices left over from an agonizing past, Hesse explores the gritty marks that trauma leaves behind.

Her illustration of the struggle sticks with you. Zofia’s grief takes on a persona of its own: It is “black ice,” the monster that threatens to grow and overwhelm her if she prods too deeply into her traumatic memories. For years during the war, she blocked them out for her own survival and sanity.

“I left pieces of myself in that car … for my own protection,” Zofia says, “because remembering that story would have demolished every reason I had to survive.”

Sympathy Forged by Sorrow

“They Went Left” also examines the complexities of forgiveness after betrayal and what constitutes humanity and inhumanity when circumstances are dire.

Through each wound or trigger, the characters demonstrate that we can only tolerate so much hurt. After losing all her loved ones and discovering the dark past of her most beloved friend, Zofia finally says, “I am exhausted by unspeakable sadness, by wearing it like a cloak.” It’s heartbreaking to read — but maybe some of us can relate to the feeling right about now.

And Zofia’s piercing pain makes her kind response all the more beautiful.

A certain amount of unabating sadness actually switches something in Zofia. She decides to extend grace where it’s undeserved, to give a traitor a second chance because some part of her anticipates that they’re just as broken as her. After chasing safety, stability and love for so long, she understands what it’s like to crave something so badly that you’ll do anything to get it.

The same experiences that broke her heart also are the ones that connect her, indescribably, to people she’s never met before.

“Choose To Love”

By far my favorite part of the book, though, was its hopeful message of choosing to create a new life and new relationships instead of being stuck in a past full of “should haves.”

As with any novel that explores the aftermath of brokenness, Hesse could easily have saturated “They Went Left” with nostalgia and regret. And she does take ample time to grieve and honor the ideal past life that seemed so effortless pre-war. But even so, the novel is gently, resolutely hopeful: Though the characters break your heart with the scars they carry, they steal your breath with their courageous decisions to move forward and create new lives out of what they have.

In one moving scene, Breine, one of the refugees Zofia meets in the refugee camp, reveals that she’s getting married to a man she’s only known for five weeks. When Zofia responds in shock, Breine says it’s an intentional choice to learn from her mistakes: She had a fiancé before the war, and she’ll always regret not marrying him. But because of that lesson, she’s choosing to love the people in front of her now.

“Today I am choosing to love the person in front of me,” Breine says. “Because he’s here, I’m here, and we’re ready to not be lonely together. Chaim is a good man. I won’t let another wedding pass me by.”

Healing doesn’t immediately come once you decide to move on, but a crucial part of recovery is the decision to stop playing prisoner to regret and start building a new life for yourself.

There are many challenges that come with starting from ground zero, and Hesse fills her story with ample evidence of the unpredictable messiness. But Zofia and her friends teach us that while there’s no way to know what curveballs life will throw your way, the one thing you can do is be willing to learn and move forward from each, no matter what.

“In a way, that’s the motto of the whole book,” Hesse said in a press interview. “We can’t choose the hate the unfolds around us, but we can choose how we love. We can choose our family. We can choose our community. We can be almost broken by the horrors of life and we can still, impossibly, manage to find moments of beauty and grace.”

Hope in Shared Human Experience

I would recommend this book to any young adult who is willing to walk the long road of sorrow with the characters to see what it’s like to come out the other side.

While the loss and heartbreak they endure are horrific, in their lows we may actually glimpse the raw confrontation of mortality we can’t find anywhere else. And watching the characters muster unimaginable courage to keep moving forward inspired me to do the same.

Maybe it’s because the tale is so firmly weighted in history that we can see our own stories mirrored in it. Many of the characters’ unexpected joys and sobering lows were inspired by real accounts of people going through uncertainty, and although we’re living in a different time, perhaps we can find comfort in the shared experience.

“I get asked a lot about how I find hope while writing stories like ‘They Went Left,’” Hesse said. “But the truth is, in real historical accounts, the hope is always there. It doesn’t look like you’d expect it to; sometimes it doesn’t even look like hope at first. But it’s there …”