When writing a memoir, the goal is to flesh out a particular facet of the author’s life to resolve the memories still attached — the trauma still lingering in the shadows of the subconscious. But what happens when the trigger to the past is pulled by a legal proceeding? A childhood murderer facing the death penalty? A stranger with a history that not only defines his story, but bites the bullet on your own “slippery notion of truth”?

The Murder

In 2003, 25-year-old Alex Marzano-Lesnevich was interning at a defense firm in New Orleans that represented and fought for clients facing the death penalty. Both of Marzano-Lesnevich’s parents were lawyers, which prompted the future memoirist to enroll in Harvard Law School. Marzano-Lesnevich, who uses gender-neutral pronouns, cited their opposition to the death penalty and, in the words of book reviewer Julia Bosson, “the law’s narrative simplicity,” as the two main reasons for their interest in the legal profession.

One of the firm’s clients, Ricky Langley, “whose sentence was overturned” at the same time, was not only convicted of murdering 6-year-old Jeremy Guillory back in 1983, but was also suspected of molesting him as well. During their orientation at the firm, Marzano-Lesnevich was shown a videotape by their supervisor where Langley confesses to his crime — along with wrapping Guillory’s body in a bed blanket and standing his lifeless vessel in the back of his closet — effectively burying Langley’s skeleton in the prison system. A cause, in fact, that brought them to reexamine everything they believed in: “Despite what I’ve trained for, what I’ve come here to work for, despite what I believe, I want Ricky to die.”

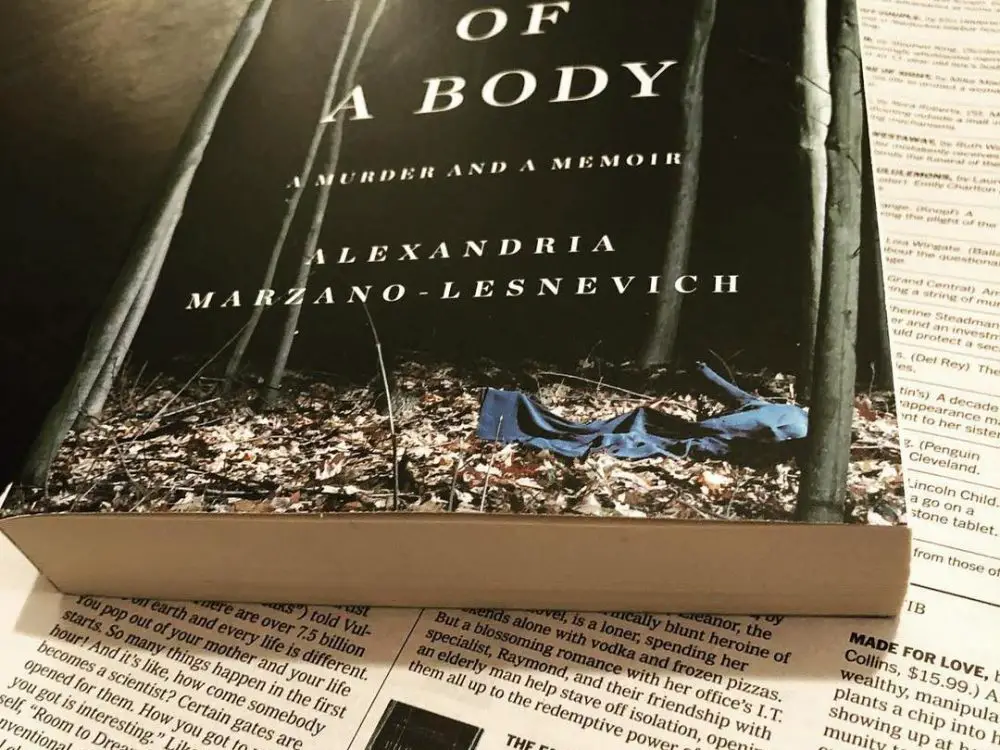

It’s rare to read creative nonfiction works by authors who were once law students. The tension between creativity and the court of law prompts interesting questions. But Marzano-Lesnevich lays bare the secrets in their 2017 memoir “The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir” that led them not only to the practice of the law, but also to the 10 years they spent dissecting Langley’s case — his life — in order to come to terms with their own.

The Memoir

According to William Skidelsky, writer for The Guardian, “Marzano-Lesnevich dives into Langley’s childhood, which [they reconstruct], often in fictionalized form, from court transcripts and other documents.”

A great challenge in nonfiction writing is the desire to create a vivid image for the reader, even though the author may not have many facts or verbal testimony to rely on. But in “The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir,” the truth consists of court records that Marzano-Lesnevich admits to using at the end of their book as the foundation to bring the scenes to life. Marzano-Lesnevich imagines Langley’s possible clothes, mannerisms, feelings and thoughts, as well as the characteristics of Langley’s mother, father, siblings, the family he was living with at the time of the murder, Guillory’s mother and the people that encountered or worked with him in Iowa (pronounced Io-way).

But where does the thin line between fiction and nonfiction become blurred? When do the envisioned backstories take away from the truth of the memoir? What about the truth of Marzano-Lesnevich’s own raw upbringing that “reckons with a past that colors their view of Ricky’s crime”?

“Memoir promises truth, and so if the book is not as truthful as the author can possibly make it, then it is not a memoir.” But in Marzano-Lesnevich’s case, the tensions between accuracy and artfulness expose the novelistic principles and problems presented not just for the writer, but for the reader as well. Their presentation of both a murder and a memoir — a hybrid, if you will — creates a book of fact and body that relies heavily on the documentation used as the primary source of the book, giving voice to the characters Marzano-Lesnevich never faced themself.

The Law

“Throughout the book, Marzano-Lesnevich employs [their] nuanced understanding of the law and instills legal terms with the kind of poetry not seen in courtroom transcripts. [They turn] the concept of ‘proximate cause’ into a fully realized parable, bending it into a motif that binds together [their] entire project.”

For Marzano-Lesnevich, or any author for that matter, to legally include investigation material, one has to compose a legal note that acts as a disclaimer on the information being included, which makes Marzano-Lesnevich’s background in law beneficial. In “The Fact of a Body: A Murder and A Memoir,” the legal note is as follows:

“This work is not authorized or approved by the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center or its clients, and the views expressed by the author do not reflect the views or positions of anyone other than the author. The author’s description of any legal proceedings, including [their] description of the positions of the parties and the circumstances and events of the crimes charged, are drawn solely from the court record, other publicly available information, and [their] own research.”

Without this, “The Fact of a Body: A Murder and A Memoir,” would be invalid, to say the least.

Moral of the story, as Marzano-Lesnevich stated in their memoir, “how you tell the story has everything to do with how you judge. And in order to judge, you need all the facts.” And to ensure that their memoir is factual and precise, a balancing act of imagination, documentary, journalism and autobiography had to be performed.

Marzano-Lesnevich has since given up practicing law and is now redirecting their focus on their writing career as an author and assistant professor at Bowdoin College.