He’s a symbol of American patriotism, of American values and of the noble American dream; he is Captain America. He is a character who could easily be understood as a symbol of American idealism, steeped in the height of the American propaganda machine that represents itself as the bastion of egalitarianism, freedom and justice.

But “The Cap,” as he is nicknamed, represents an America of the imagined past. The comics follow the character as a hero reborn (thawed, really) in a modern time, and this has always put him in conflict with the modern entity he is supposed to represent.

This is the foundation of “Captain America” as a series. And it is the ripe ground on which Ta-Nehisi Coates has been building his own arc for the character.

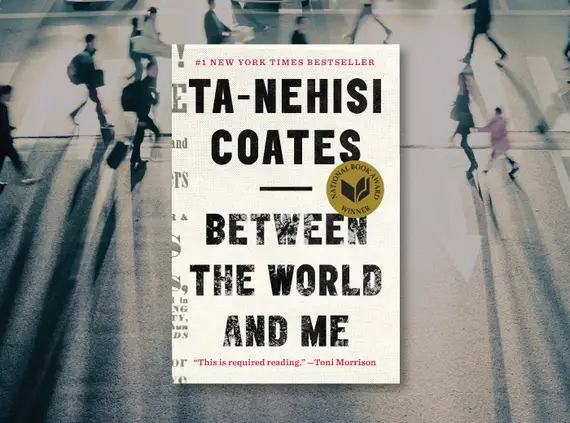

Coates is authoring the newest volume of the “Captain America” series, set to release on July 4 of this year. He has an extensive history as a correspondent for The Atlantic and as the author of the acclaimed “Between the World and Me.”

Coates has carved out a reputation for himself through his explicit presentation of the black experience in America, as a critic of the Obama administration and as a writer who compellingly wields historical narrative.

Coates has a profound understanding of America as a place with the potential to be wonderful with a very visceral experience of its absolute worst. He writes, “America believes itself exceptional, the greatest and noblest nation ever to exist, a lone champion standing between the white city of democracy and the terrorists, despots, barbarians, and other enemies of civilization.”

Coates presents the potential to show America’s most ingrained struggles through the use of one of its mainstream pop cultural symbols.

The Atlantic contributor only recently began writing comics, beginning with a new rendition of the “Black Panther” series. He modernized the character and the imaginary civilization of Wakanda to fit with a contemporary audience.

“The Black Panther” appeared as the first black superhero in a comic book back in 1966, amidst huge waves of social and political upheaval. Ever since, the character has been grounded as a major symbol for black representation in mainstream culture, although Black Panther was still a marginalized character. This series has earned Coates a significant following, showing that he has a great competency for the medium despite his nascent entry into the genre.

Perhaps it was a natural transition in his creative life because of the presence of comic books in his childhood. Reading comics was one of his principal pastimes early in life and one of his first introductions into the world of literature and language.

This makes the opportunity to write comics himself a natural realm in which to exercise his thoughts and writing ability. In an interview with NPR’s “Code Switch,” he compared superheroes to the pantheon of Greek gods— “[they] are our mythology… [they say] something about how we imagine ourselves.”

He said this in the context of a question about representational diversity in the comic industry. His answer hints at the weight that superheroes carry not only for him, but in the mainstream media and its influence.

It can be easily argued that the entertainment industry is America’s mythology; it subtly informs its citizens’ values and their image of themselves. And Coates has at his disposal an instrument he can use to engage that image and invite reflection.

Naturally, Coates has some definite intentions in mind for these endeavors. At the end of the NPR interview, he touched on his perceived responsibilities as a comic book writer: “A.) You have an imperative to really interrogate what our imagination actually is and B). You have an imperative to depict the world as it is with some fealty and some loyalty.”

This is the mindset that Coates is bringing to his work as he interprets the legacy of “Captain America.” For him, The Cap’s story embodies a struggle on the question of what it means to be patriotic and what it is that America is supposed to represent.

For Coates, this presents a way to consider these questions himself. On his blog in The Atlantic, Coates expressed his association of “Captain America” with the American dream, a reality that he has never had access to as a black man.

Coates grew up in the segregated Baltimore of the ‘80s and ‘90s. He experienced the violence and suffering of the crack era firsthand. He was indoctrinated into the survival mentality of his community. This is what he conveys in the opening pages of “Between the World and Me,” a gut-wrenching account of what to expect as a black body in America that Coates wrote in the form of a letter to his son.

This is not the American dream that the Captain represents. That contrast is what makes the author’s undertaking of this project so particularly striking. Coates is poised to confront these experiences through a character who represents ideals that were never available to him as a person of color.

The interesting take here is that it is not Coates’ intention to exploit the character as a way to exert his own biases, but the opposite: “[he is] attempting to put Captain America’s words in [his own] head. What is exciting is the possibility of exploration, of avoiding the repetition of a voice [he’s] tired of,” said Coates.

Coates expresses an incredible cogency in knowing the gravity of his place as an author for this series. He is well aware of the connotations of his position, and he is choosing to approach it in an intelligent manner that doesn’t just preach his own rhetoric.

Through “Captain America,” Coates is coming to grips with his own definitions of what it means to be patriotic and what it means to believe in the American dream. The many iterations of the comic book character share the legacy of facing these dilemma-causing themes.

The difference is that none of those other series have ever been written by a black man with the strong political perspectives that Coates brings to the table. If the author’s previous work can be taken as a sign, then we should expect an incredibly scrupulous inquiry into the pillars of American values.