Sure, you can sell your organs to pay back your dead father’s debts, but the yakuza will only repay you by turning into zombies and disemboweling you. That’s fine, though. Your closest friend is a loving dog with a chainsaw in its face, and it’s willing to give you immortality and the ability to turn your own face and limbs into chainsaws. And sure, you’ll lacerate them into soggy ribbons, but you’re a devil now — the very thing you’ve been hunting for extra cash. Luckily, you’re found by a government agency that wants to put you into an experimental devil hunting unit. You’re openly referred to as expendable by the agency, and your odds of slaying its enemy, a devil of cosmic proportions, seem slim.

This is “Chainsaw Man,” Tatsuki Fujimoto’s new manga series. Shonen Jump, a popular boys magazine in Japan, publishes a new chapter of the series each week, and the series is currently at chapter 42. “Chainsaw Man” is Fujimoto’s follow-up to his popular “Fire Punch” series, which was also published through Shonen Jump.

The series has yet to reach the popularity and sales figures of other Shonen Jump series — “Kimetsu No Yaiba,” “One Piece,” “My Hero Academia” — but it has retained its place in the top 10 most popular Shonen Jump series. Shonen Jump includes a popularity survey in each issue, and the results are used to decide which series remain in serialization.

Although Denji’s life as a debtor comes to an end in the first issue, the lingering effects of his former lifestyle are apparent in his actions and point of view. His government job gives him a security he’s never known; he is completely satisfied with having options for breakfast. His adoption by the agency also has the effect of introducing him to the possibility of living a normal life, but he’s also made to feel like an unnatural human weapon.

Chainsaw Man, Ch. 41: A little ice cream downtime between killing devils. Read it FREE from the official source! https://t.co/le4WkfSNsq pic.twitter.com/IPTPkIVBmg

— Shonen Jump (@shonenjump) October 6, 2019

Denji’s laughably immature attempts at human connection initially come off as just a parody of the typical Shonen protagonist’s unwavering focus; however, the naïve objectification at the heart of his initial dream reaches a sobering conclusion. This might’ve been just a simple coming-of-age moment for Denji, but “Chainsaw Man” connects this outcome to larger themes surrounding the validity of dreams within a system that devalues the individual.

“Chainsaw Man” uses Denji’s viewpoint sparingly by placing him in the context of a densely populated and detailed world. The manga refuses to position him as a rebellious savior to a strict system, unlike the plots of many dystopian novels. There is no concrete answer or approach for the fundamental issues of their world, and “Chainsaw Man” only hopes its characters can find peace in the inessential moments between each successive tragedy.

The tragedies are all a result of the constant battle between humans and devils.

The devils are all based on items, animals and concepts, and their individual power is based on the public perception surrounding each devil’s namesake. The world of “Chainsaw Man” builds several agencies in order to defend against the various levels of mayhem brought by each devil. They range from the relatively weak sea cucumber devil to the incomprehensibly powerful gun devil. The devils’ ubiquitous presence is as much a source of suffering as it is a necessity in defending against the new threats they pose.

The devils’ power is shared with humans in three ways: deals, fiends and devil-human fusions. The deals have to be made directly with devils, and a deal will frequently cost someone a limb or a portion of the user’s lifespan. Fiends are devils possessing corpses; they are uncontrollable threats, but Denji is paired with a few of the more human fiends. Denji’s place as the sole devil-human fusion, which has currently unknown implications, is an encapsulation of his own feelings and changes the way he is perceived by the agency.

Before he met the agency, Denji was someone whose value was determined by his ability to make money for exploitive yakuza, and his chainsaw was his greatest asset in paying back this debt. The chainsaw dog is both his only real relationship and the only thing making him valuable in the eyes of the people who control him. He eventually becomes one with his tool, and this opens up a new world to him. The symbolic fusion conveys a lot of the ambivalence at the heart of “Chainsaw Man.” Is serving a conspicuously exploitive system a fool’s errand, regardless of one’s intent? Can the personal pleasure of performing a task well be separated from its place in serving the common good?

Denji and his team might be working toward prolonging humanity’s time on earth, but the agency guiding them is flagrant in its disregard for individual safety and humanity. The agency is initially characterized as overwhelmed dorks, but a turn halfway through the series recontextualizes them as a merciless machine.

Good news! A manga called Chainsaw Man exists! https://t.co/7RceBJpDJf pic.twitter.com/RbCyPFp8Ya

— Shonen Jump (@shonenjump) December 6, 2018

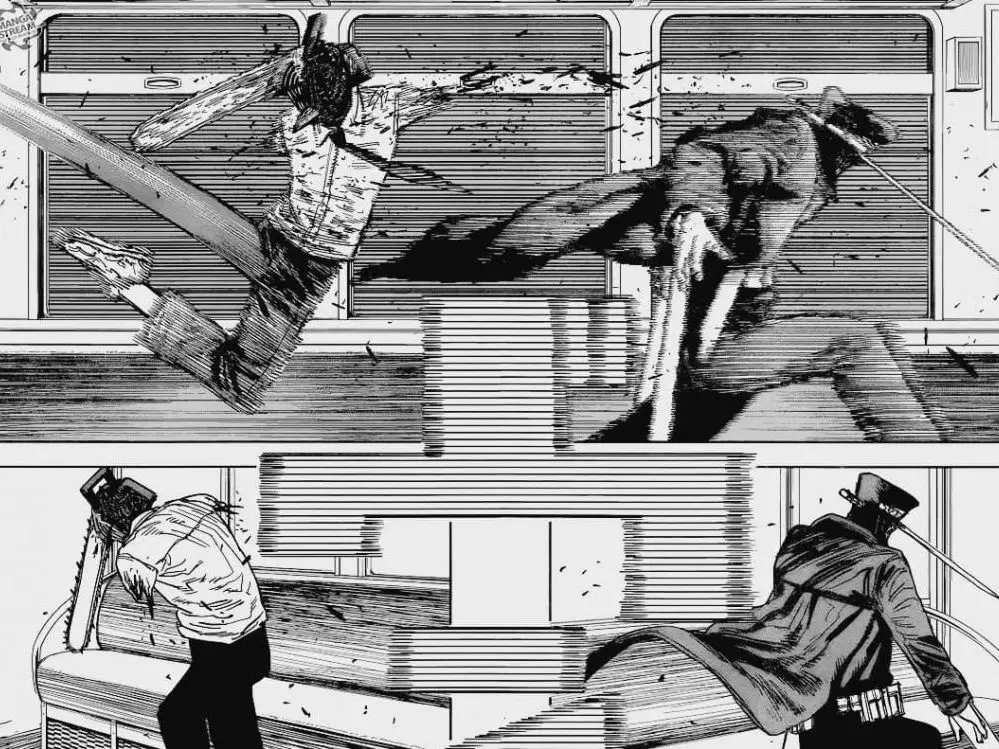

The unrestrained violence of “Chainsaw Man” arrives at the moment Denji has his first chance at freedom. Throughout the series, Denji reverses hopeless situations with his reckless courage. The series’s bloody sections create a unique connection between you and Denji; the goopiness of it all is just a bit of frivolous excess to derail the manga’s gloomily logical surroundings.

The hurried, sketch quality of “Chainsaw Man” serves its approach to gore, devil design and movement. The fight scenes of “Chainsaw Man” are built around constant penetrative chainsaw lunges and corresponding geysers of blood, and the rough lines give the bloodiest scenes a necessary freneticism. This approach is also essential in expressing the messiness of a constantly moving chain tangling flesh.

The rough lines are also reflected in Fujimoto’s portrayal of world-weary characters; the author distances himself from unblemished cutesiness typical in manga in favor of making the characters’ traumas feel inherent in their designs. Fujimoto has little interest in wasting time on backgrounds during the more contemplative scenes; he would rather express mood through subdued close-ups, which eschew everything but a character’s face. The emotional moments don’t ride on the complexity of a single facial expression. Instead, these panels accumulate a dramatic weight through repetition and page real estate.

The devils of “Chainsaw Man” are discomfiting distortions of expected forms. The style expresses the devils’ unfathomable and amorphous forms. Although the style is superficially messy, the series’s devils show how intricate, grandiose messiness can make a form feel especially uncanny.

Fujimoto’s panel layout is notable in how it utilizes many of the same techniques across its action, humor and expository sections. Repetition in the action scenes is mostly present in a detailed attention to background characters and objects; things and people will occupy the background of multiple frames only to gain an unexpected relevance on the next page.

The focus on repetition in action is also reflected in contrasting stillness with frenzied motion. Still panels are essential to communicating a fight’s unexpected turns. The battles rarely have moments of clever strategy, so poor timing, unplanned reinforcements and brute force can each play a large role in determining an outcome. The restrained use of still panels amongst the intense action captures the desperation brought about by each unexpected change.

The scenes outside of the action use the same repetition and unexpected significance to tell jokes and express dread outside of the series’s more bloody scenes. Reusing techniques for different purposes creates a clear visual language while still maintaining a sense of total unpredictability. “Chainsaw Man” also presents a clear dichotomy between action and non-action segments by making the action scenes’ panels feel jagged.

“Chainsaw Man” allows the most carefree characters to feel existential dread with the same frequency it allows its gloomiest characters to be silly. The series might not allow any easy explanations for the problems of the world, but it never feels hopeless. Human connections struggle under rigid systems and dire situations; however, the necessity of these connections defeats any of the things that might prevent them. By providing an honest look at the myriad wrongheaded ideas behind the characters’ many hopes and dreams, “Chainsaw Man” establishes a hard earned appreciation for humanity. A species that unwinds with chainsaw fights can’t be all bad, right?