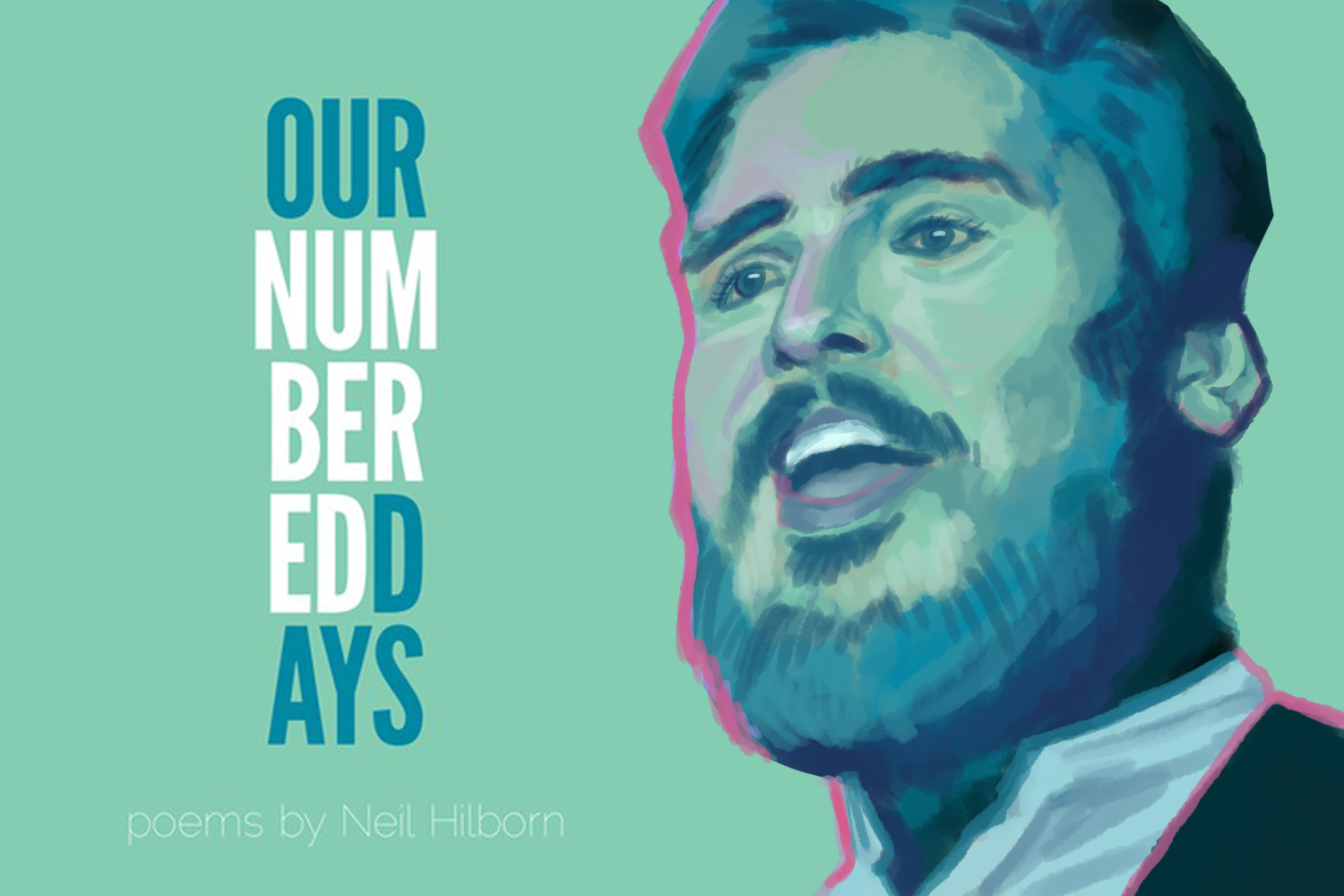

Neil Hilborn’s 2015 debut collection, “Our Numbered Days,” delves deep into the mania that mental disorders create for the afflicted person and everyone on the outside that’s also impacted. The Houston-born poet pens his experiences with melancholy and maddening banter about loss, mental illness, suicide and the tragically beautiful phenomenon of love. The collection is composed of his slam poetry performances, which grew from the more than 14 million views of his remarkable presentation of “OCD.”

The premise of the work is to recognize that the bad days are temporary and should not further limit you. Hilborn does not allow his mental illnesses to take over his life and that message should be heard worldwide.

The most integral aspect of this 55-poem compilation is the continuation of the title poem, “Our Numbered Days,” which appears seven times within the 63-paged book. Each segment of the poem begins with a series of relevant quotes that influenced the author at that point in his life and his writings.

The poem “Our Numbered Days” begins with the agony he will feel when his mother passes away, continues with the hole an absentee father creates and transitions into the roller coaster that follows those with obsessive compulsive and bipolar disorder.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, one in 40 adults (2 percent of the population) will be diagnosed with OCD, and almost 3 percent will develop bipolar disorder at some point in their lifetime. It’s easy to forget that there are others who have shared similar experiences as you, but Hilborn’s personal recollections make the world seem smaller, more manageable and relatable.

The sixth section of this seven-layered poetic piece makes the reader stop and contemplate the most because the slam poet catches you off guard with a direct fear of his illness. “I am concerned/that if I begin taking/medication I will no longer/be able to write poems.”

Throughout each of his pieces, Hilborn, for the most part, leaves the symbolic language up to the reader to unravel, but this stanza from the title poem stops you dead in your tracks. The imagery has faded and you are left with nothing but the cold, simple words.

This bluntness illustrates that once you acknowledge your phobias they lose their power to stop you from living. It is empowering to stand up against your worries, and these poems give you the strength to do so without undermining how debilitating they can be.

Hilborn also uses dark humor to talk about his mental disabilities, such as in “All Harvestmen Are Missing a Leg,” “The Talk Show Host Has a Nosebleed on National Television” and “I’m Sorry Your Kids Are Such Little Shits and that We Are in the Same Zen Garden.”

For instance, “All Harvestmen Are Missing a Leg” describes the crippling anxiety that stems from his fear of driving because, according to the poet, St. Paul drivers have broken their ankles. The dark humor peaks through when the Minnesota resident explains that a harvestmen “is referred to by the unimaginative South as Daddy Long Legs.”

Hilborn furthers his cynicism in the lines, “though I admit it would be/funnier to imagine all people who harvest/ hopping on one leg. Not funnier. Did I say/funnier? I meant somber and embarrassing./I meant whatever doesn’t offend you.”

Mental illness is not the only adversity the poet is plagued with. “Joey” is about Hilborn’s friend, who, when he was 17 years old, also had mental health issues, or, as he puts it, “the mental disorders I call friends.”

Joey attempts suicide a multitude of times because his family could barely afford rent, let alone a therapist and medication, so they were unable to help with his disorder. The third stanza, however, takes a more hopeful turn. The poet writes, “Joey isn’t going to kill himself/twenty more lines into this poem. That’s not/the kind of story I’m telling here.”

Joey’s story continues with all the ways he tries to kill himself. Hilborn explains how Joey ”molded his car into the shape of a tree trunk” or when he was “staring at his scalpel/like he wanted to be the frog.” Hilborn even recollects the moment he made Joey feel like a pariah because of his disease. He says, “We were 17 and the one time Joey/tried to talk to me about being depressed/when someone else was around, I told him to/shut the hell up and asked if he needed to change/his tampon.”

“Joey” is not the only poem about a friend committing suicide. Hilborn talks about his friend Alex, who “chose to die five years ago,” in two little poems. One poem is about the constant memories a person is consumed with after a sudden loss. The poet declares that he is not finished with remembering his friend, so every time he scribbles Alex, he purposely forgets the “E.”

Losing someone you love can be incredibly distressing, whether they have been taken away by death, breakup or unsolvable problems. “Enabling: a Loving Song,” another poem about loss, tells the story of Hilborn’s grandmother as she tries to speak to her late husband, Bob.

The poem talks about how his grandma’s alcoholism has left her debilitated, confused, regretful and lonely. Her mind evades her as she keeps saying her lover’s name. Hilborn writes, “Even if/I could have said anything else, I wouldn’t.” The widow holds close the love she and her husband shared, despite the troubles they faced, even forgetting what life was like before he came along.

There is hope and sadness within Hilborn’s collection of poems, which can help act as a guide for readers hoping to navigate the turmoil of their own lives. I recommend the collection for all types of readers, regardless of whether or not you’re interested in poetry.