It’s been 10 years since the publication of Jericho Brown’s book of poetry “Please,” and yet the vivid tides of language packed into the 63-page collection still stagger, still manage to burn a hole through the heart and fill it up with something heavy.

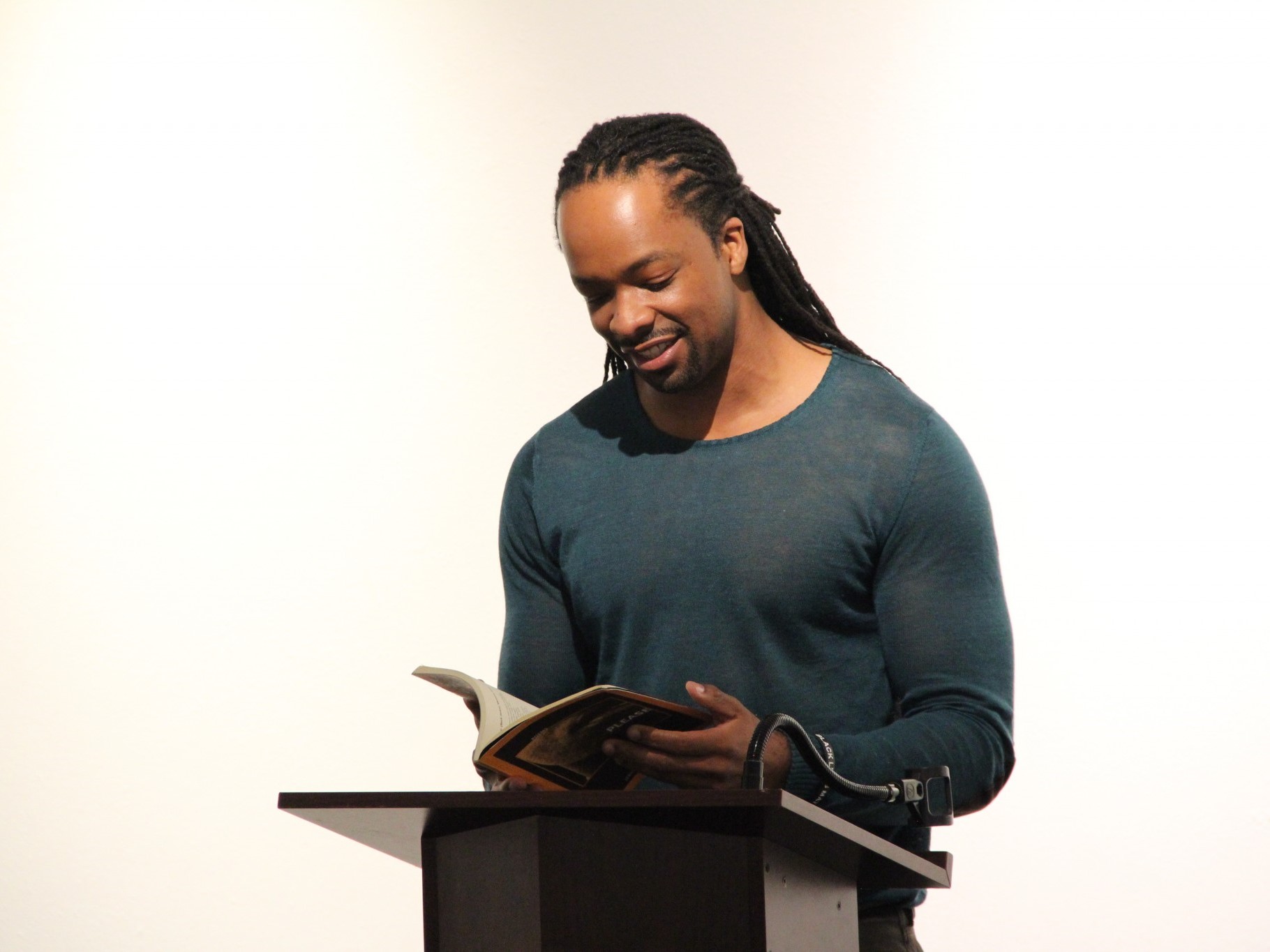

At the heart of “Please” — winner of the 2009 American Book Award — is the lyrical and powerful voice of Brown, each word tumbling off the tongue like the drop of an anvil. The author is a master of words, having taught classes and workshops at many notable universities across the nation, as well as having worked as the speechwriter for the mayor of New Orleans. Additionally, he’s been awarded several top fellowships, including the Guggenheim.

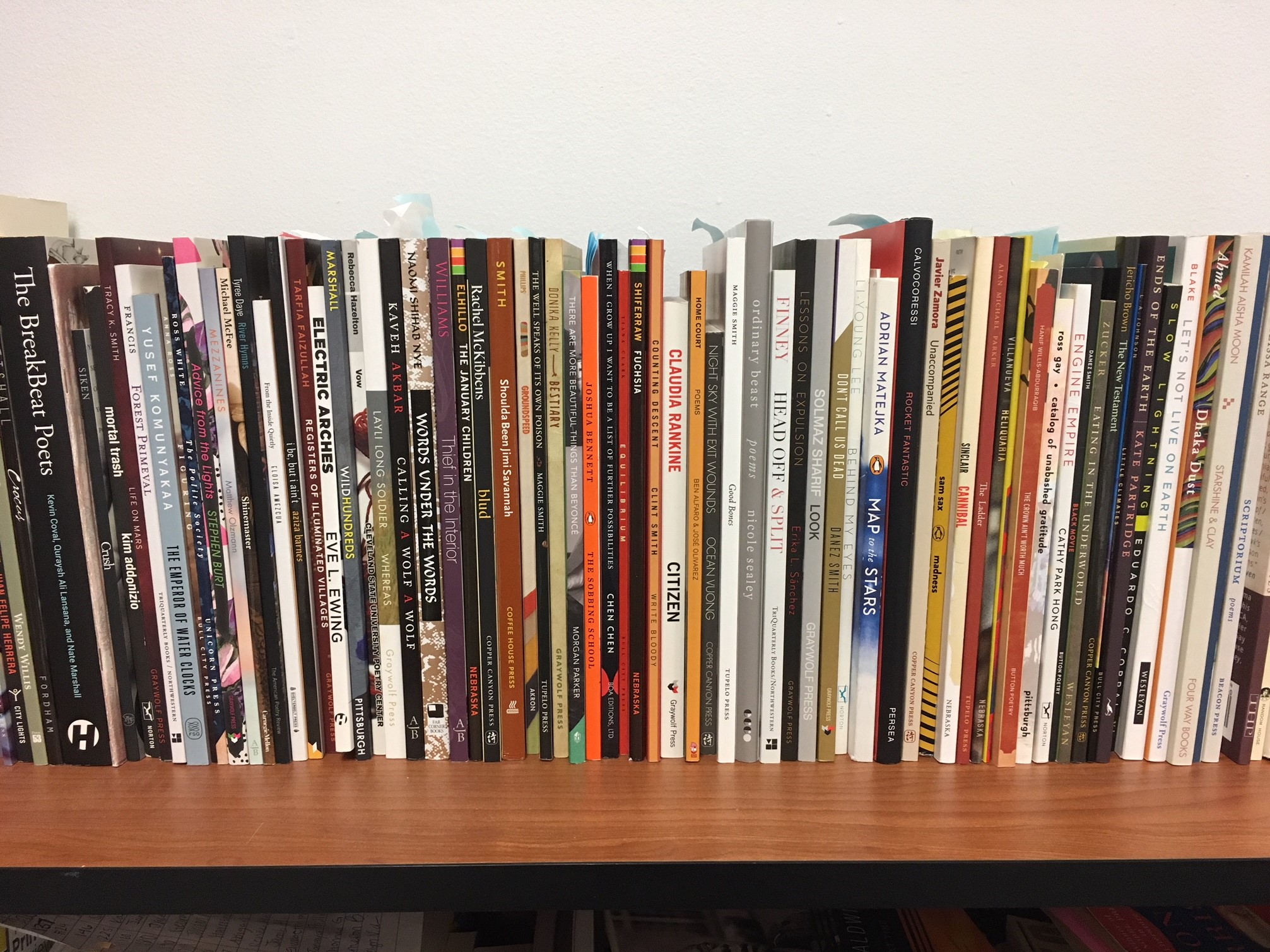

His expertise shines unbridled in “Please,” slipping into rhythms and beats as the poems move between the collection’s four sections: Repeat, Pause, Power, Stop. In fact, music is a central root tethering the poems to each other page after page. Not only are the sections aptly named after buttons on a stereo system, the collection is full of musical anecdotes. Lyrics and song references pop up in symphonic stanzas and titles, imploring the reader to exist within the melody of the poems while listening to the overlapping voices of Pink Floyd, Marvin Gaye and Donny Hathaway. Their songs, often presenting themes of loneliness, suffering and identity, weave their way into the sound of Brown’s own poetic blues.

What lives inside this blues is a thread of familiar planes central to an individual’s life. While Brown writes as a gay, black man — and the themes expressed throughout the collection highlight the ins and outs of said particular background — his poems are not exclusive to any one person. Rather, “Please” sits within the weight of collective human experience.

The subject of identity, something Brown explores at multiple angles, is something all people have struggled with. In “Please,” the poet delves into the concept of masculinity, particularly how it relates to sexuality, throughout the book. “Like Father” describes an interaction between a father and son, with Brown writing, “My father’s embrace is firm and warm … he begs forgiveness for anything he may have done to make me turn to abomination.”

The speaker’s masculinity in the father’s eyes is held together solely through a tight hug, though it remains uncomfortable; embracement of one identity leads to disruption in another. In “Lunch,” Brown depicts how harmful, shared hate feigns masculinity. You swallow toxic homophobic slurs and spit out a smile, try to remain appropriate to retain safety.

Safety, or the mundane-ness of tragic survival, bounces off the pages here, too. “Track 5: Summertime” literally screams off the page, conjuring up images of being slapped with dirty pads and young boys whipped on street corners. “I try so hard to sound jagged,” Brown writes. Violence only makes the heart harder.

What Brown makes strikingly obvious, though, is the fact that violence is often a private affair. Pain, the kind of loudness that makes glass shatter and skin bloom with muddy bruises, is the language of the home, of family and even love. In “Again,” Brown tells the story of a mother and son running away from their home, only to retrace their steps back to the front door. “My mother loves her husband and his hands even if laid heavy against her,” he writes. Brown conveys how the air of the home is often thick and dripping with brutality, an experience many have become comfortable with. The day-to-day-ness of atrocity makes it almost casual, something that goes hand in hand with Brown’s slightly conversational voice.

Even subtler articulations of this reality permeate the language of “Please.” Race-related conflicts bend and muddle the discussion of violence Brown cements throughout the collection. “Detailing the Nape” connects the black and the bloody, highlighting the problematic notion of colorism. “Rick” mirrors the anxieties of interracial relationships.

Despite all this, Brown’s approach doesn’t seem to be an argumentative one. More so, he is speaking to himself, venting onto a piece of paper and sealing it in a bottle, setting it adrift. Whoever uncovers it dives headfirst into his words, raw and broken but always refined. There’s willingness and an acceptance of struggle in “Please” that distinguishes it from some other works of poetry. Pain is blatant but it isn’t insisted upon. Brown doesn’t have a call to action; he asks readers to listen, even where there is silence.

So why should you read “Please”? It’s certainly not your classic summer read, nor is it the book you curl up with on the sofa as the snow falls in soft layers around you. But whether you relate to Brown on a personal level or on the bubbling surface of the themes he presents, there is something for everyone in “Please.” The book has a beating pulse; something lives there on the pages. Whatever feelings may strike as you read are necessary to feel.

To pick up a copy of “Please,” to bend back its pages and doggy-tag the crisp corners when the words hit you like a punch to the heart, is to fall into the magnitude of the title’s evocative tone itself. The book is a plea, a hand reaching out from the curves of the letters and the binding of the spine. Brown folds his experiences into a question, a calling out for air. What else is there to do but answer?