“Make me a sandwich!” one boy yells from the back of the classroom. The eye-rolling phrase cuts off the new girl while she is speaking. She points the interrupter out to the teacher, but she is punished for speaking her mind while the interrupter and friends snicker like nothing can touch them. Sixteen-year-old Vivian Carter watches in shock at the beginning of the first chapter of Jennifer Mathieu’s young adult novel “Moxie.”

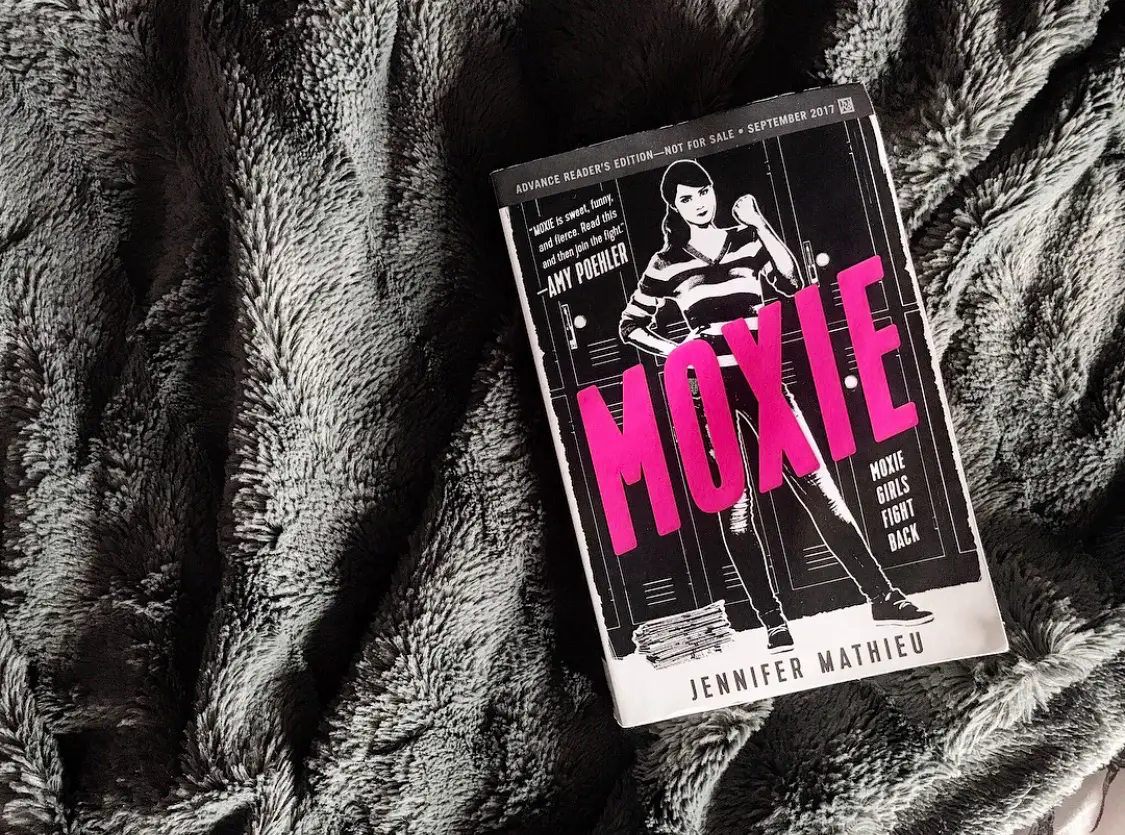

After this incident and seeing a guy walk through the hallway with a sexist t-shirt, a livid Viv creates an anonymous zine, called “Moxie,” to air her pent up frustration toward a select group of guys at her school. At the end of the first issue, girls are instructed to draw hearts and stars on their hand to support what the first issue’s content and find other girls who agree with “Moxie.” As the sexist incidents continue to worsen, the retaliation grows stronger. Mixing a dose of unapologetic feminism with a smattering of female solidarity, “Moxie” introduces a new generation to the zine.

According to the Barnard Zine Library, a zine “is a DIY subculture self-publication, usually made on paper and reproduced with a photocopier or printer.” Although the first zine came out in 1930, zines didn’t start becoming political until the ’90s riot grrrl zines, which were explicitly feminist. In Mathieu’s novel, Viv’s mom has a box labeled “MY MISSPENT YOUTH” hidden away in her closet that contains all of her ’90s Riot Grrrl memorabilia. The night Viv makes the first issue of “Moxie,” she draws inspiration from the female-led punk band Bikini Kill zine she found in the box.

Throughout the novel, several protests take place to bring attention to the issues plaguing the female students at East Rockport High. Without spoiling the ending, I can tell you that Viv and the other students are able to bring about positive change to her school, a change that wouldn’t have happened without “Moxie.” Here’s why the zine was effective in changing the culture at ERH.

The novelty of the zine pulls in more readers. I don’t think the other students were exposed to zines before. The word “zine” is not in their vocabulary. Everyone instead calls “Moxie” a newsletter, which slightly makes sense considering that the zine sometimes acts like a newsletter. Viv writes quick bullet point statistics to go along with her report of the latest thing some guys have done at her school to terrorize girls.

Because the students don’t know what to make of Viv’s zine at first, they view it as an intriguing point of conversation. The events of the novel take place in a really small town, so I’m assuming that anything remotely out of the ordinary will be scrutinized. People can’t help but talk about the zine. If everyone is talking about something, it makes you more curious to see it for yourself. I think “Moxie” had sort of a ripple effect when Viv first placed it around the school.

“Moxie” required participation from its readers. At the end of each issue of “Moxie” is a protest for readers to do that brings the girls of the school together. Lucy, the new girl who Viv befriends, even noticed when one issue was missing what she refers to as a “call to action.” For instance, when the school administrators start getting out of control with enforcing the dress code, Lucy releases a “Moxie” that instructs other girls to wear a bathrobe to school. Some girls actually do it.

The protest works because it catches the attention of administrators and teachers. It gets on administrators’ nerves because they can’t do anything about it. Bathrobes are technically not against dress code, which further drives home the point that the high school’s dress code is too vague. The protest is a win for students, and there are no more dress code checks after that.

It’s easy for readers to participate in the protests. Viv never suggests to do anything expensive or wild. She makes up creative yet simple protests that everyone can do like the putting on bathrobes. There was another protest where she provided stickers with an insulting phrase on them to the girls, so they could stick them on the lockers and various items belonging to boys who participated in the bump’n’grab game (a boy bumps into a girl and gropes her).

Publishing “Moxie” anonymously was the smartest decision on Viv’s part. At first, I wasn’t sure if “Moxie” would have as much power if she didn’t attach her name to it. Normally, it seems like people want a face for a movement. But I think the anonymity worked for two reasons.

If Viv revealed her identity sooner, I don’t think the other students would’ve taken her seriously. She was this shy, tall girl who tried to fade into the background. Her mom and grandparents see her as a good girl. The other students see her the same way. Although she is quite tall (5′10″ to be exact), she never mentions anything in the book about being bullied.

Viv explicitly says she wants “Moxie” to belong to everyone. She feels like her classmates would’ve been distracted by a leader. Readers see Viv’s reasoning validated when other girls start planning their own Moxie events such as a bake sale, arts and crafts show or a walkout. When her classmates plan these events they don’t ask anyone to do it, they just do it. I think that’s exactly what Viv wanted, so then Moxie would actually begin evolving into a movement rather than just her calling the shots.

“Moxie” turned a school with a complete disregard for the way young women are treated into a regular learning environment where students can come to school free of any worry that someone will tell them to “make a sandwich.”