A few years ago, if you had given someone 10 seconds to name a famous living poet, there’s a good chance an answer wouldn’t have left their lips — and if you had given someone 10 seconds to name any poet, regardless of whether they were alive or not, there’s a good chance Maya Angelou would have been their only answer. In 2015, poetry was one of the least popular art activities for American adults, with under 10% picking up a book and reading for pleasure.

In 2012, fewer than 7% of Americans had read poetry, which was down from 17% in 1992. That was the steepest decline found in any genre of literature. Unless you were some type of literary scholar, an English major or just a poetry fanatic, there was a good chance you didn’t know much about the art form. Just when it seemed like the genre was on its deathbed, Instapoetry — simplistic, easy-to-understand poems short enough to fit into your Instagram bio and make you seem mysterious and deep — came to save the day.

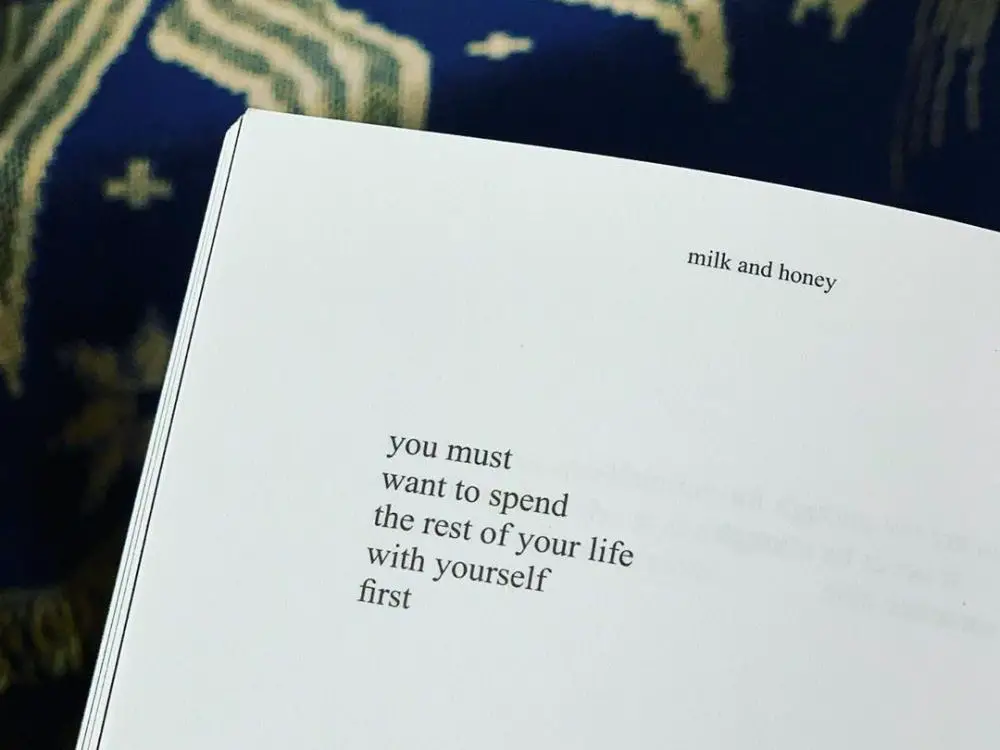

Instapoetry emerged thanks to social media, specifically Instagram and Tumblr. Instapoems are crafted with the intent of being shared — they’re usually no longer than a few lines, extremely direct and come in aesthetically-pleasing fonts. They often discuss subjects such as sexuality, mental health, love, feminism and domestic violence. Some of the most notable Instapoets are Atticus, Amanda Lovelace and Rupi Kaur, whose debut collection, “Milk and Honey,” garnered as much controversy as it did praise.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B8jkP41hQ5C/

The impact Instapoetry has made in the poetry world is immense. In 2017, poetry sales were twice what they were in 2016, thanks to Kaur’s publisher, Andrews McCeel, and 12 of the top 20 best-selling poets were Instapoets. In 2018, 28 million Americans were reading poems, which was the highest percentage of poetry readership in almost two decades.

Instapoetry is raved about. The fact that it’s straightforward while also being heartachingly confessional is what appeals to many. Before the dawn of Instapoetry, many people typically thought of poetry as being long and difficult to decipher. Reading poetry almost seemed like trying to understand a foreign language, and the confusing nature of all the similes, metaphors and imagery pushed people away.

With Instapoetry, the intent of the author is easily understood. Readers don’t feel stupid or think the work needs to be dissected. It’s a digestible, simple beauty. You scroll through your feed, take 30 seconds to read it, bask in how well-written you think it is and then move on with your day. Instapoetry allows for anyone, including people who, in the past, might not have normally been given the opportunity to showcase their work. These Instapoets don’t seem like untouchable authors. They’re normal human beings that you can easily access with the click of a button, who go through the same struggles everyone else does.

It’s not all sunshine and rainbows, though. Instapoetry has also been the subject of some harsh criticisms. It’s been accused of having no meaning or substance, of seeming like passing thoughts thrown on paper, wrapped up all pretty and distributed to the masses.

“[Instapoetry] is not poor because it is genuine, it is poor because that is all it is. To do more than that, regardless of talent, requires time, and, by its very definition, Instapoetry has none,” Soraya Roberts wrote in The Baffler. Instapoetry is consumable inspiration, attractive and quick. This formula is so transparent that it’s produced parodies and memes. On Twitter, there was a time where people would tweet imitating Kaur’s style of writing. “Milk and Vine,” a poetry book parodying “Milk and Honey” using quotes from famous Vines, became a No. 1 Amazon best-seller.

He

Sent

Her

A

Meme

On

But

She

Already

Saw

It

On– Rupi Kaur

— Azeem (@_azeem87) April 6, 2019

Instapoetry has also been seen as a disgrace to writers who have worked tirelessly to hone their craft and achieve recognition. There are many poets who have gone through countless rejections to get to where they are now, and even some who haven’t yet had their big break, so why should these bite-sized poems that appear to have no depth get all the attention? To critics, it’s seen as “not real poetry,” but then again, what makes real poetry? And who is anyone to gatekeep, or decide who gets a pass to join the secret poets club?

There are a lot of things right and a lot of things wrong with Instapoetry. The answer as to whether it’s destroying the art of poetry or not is subjective. It’s revived the general public’s interest in poetry once again; it’s fresh, untraditional, current and now. For art to sustain interest, it must always go with the times, adapting and changing with its audience. Art should break boundaries, even if it’s not always appreciated.

Looking back, there are styles of poetry that used to be looked down on that are now recognized as being extremely influential, such as Beat poetry. Beat poets rebelled against mainstream American life, and at the time, were looked down on for being for too nihilistic or unintellectual. Instapoetry is being looked down on now, but generations from now, it could be studied in schools or hailed as one of the greatest poetry movements to ever exist.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B7byzW6pCqC/

Then again, there are a lot of valid concerns about it. For people who love to read, write or study poetry, it’s scary knowing that someone can take an art form that’s known for requiring time and dedication and endless revision and just twist it on its head. It’s scary knowing that someone can just jot down a few “deep” words on a page, post it online and become rich off of it, leaving the great poets of the past and people who have had to work hard to achieve fame in the poetry world to rot.

In a world filled with an overwhelming amount of entertainment, people are leaning toward things that are louder, flashier and not so time consuming. Instapoetry fits the bill perfectly. While poets who prefer to stick to traditional poetry should absolutely keep writing, Instapoetry could be just what the poetry world needs to get it back on its feet.