Across all types of media, there are specific standardized practices that creative works are expected to follow. Whether it determines the way camerawork is handled in films or how sheet music is structured, creators adhere to artistic norms due to their proven efficacy. However, most art forms contain a few notable exceptions that ignore tradition to create memorable, one-of-a-kind experiences.

Movies like “Paranormal Activity” and “The Blair Witch Project” and “Hardcore Henry” use found footage and first-person camerawork to deliver stories through uncommon perspectives. Similarly, games like Undertale and the Stanley Parable recontextualize familiar styles of gameplay to satirize and subvert their respective genres. Even paintings such as Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Ambassadors” and photographs like the “Representations” series by Cynthia Greig serve as creative pieces that take full advantage of their mediums.

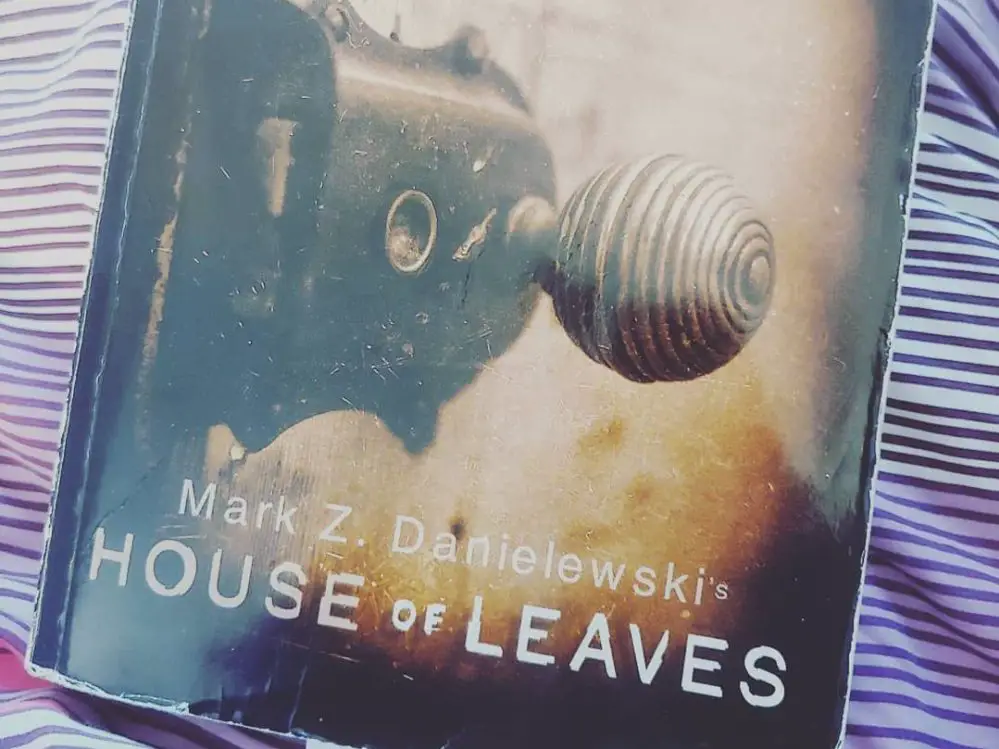

In contrast, books offer much less opportunity for creative deviations from standard storytelling. The limited presentation of printed text doesn’t provide authors with the same degree of creative expression as other mediums. As a result, few books ever stray from the tried-and-true format of conventional literary storytelling. However, one exception can be found in Mark Z. Danielewski’s debut novel: “House of Leaves.”

First released in 2000, “House of Leaves” comprises three distinct parts, all told simultaneously. At the forefront is the story of Will Navidson, a photojournalist who plans to record a documentary about his family’s move to a seemingly ordinary house in Virginia and the mundane journey of adapting to a new community. However, his focus shifts once he notices odd occurrences around the house, such as discovering the building’s interior is inexplicably larger than its exterior or finding a hallway that stretches to absurd lengths. As Navidson and his family investigate these incidents, the house gradually reveals more of its underlying secrets through increasingly erratic and threatening events.

While the Navidson segments sound like any other haunted house story, “House of Leaves” presents this concept with a unique twist. Most of the novel takes place after Navidson’s recordings were publicly released as a documentary called “The Navidson Record,” with readers slowly uncovering what transpired at the house through an unfinished analysis of the film written by an enigmatic writer named Zampanò.

This means the bulk of “House of Leaves” is formatted like a biography, complete with footnotes and citations of various photographs, interviews and research papers. Some of these sources are real, but most of the works Zampanò references are completely fictional. However, he describes these made-up sources with incredible detail and believability, helping the reader understand the scientific research and speculation surrounding the house and its inhabitants. Zampanò’s in-depth exploration of “The Navidson Record” demonstrates how the overarching world and story of “House of Leaves” extends far beyond the Navidson residence, making it easy to forget that the novel is entirely fictitious.

Danielewski’s ability to make such a believable biography about an obviously impossible topic becomes even more impressive considering how the novel begins. “House of Leaves” opens with a preface by Johnny Truant, a tattoo parlor employee who discovers Zampanò’s incomplete writings shortly after his death. Truant’s interest in “The Navidson Record” drives him to piece together the deceased writer’s collection of pages while conducting his own research into the mysterious house.

However, his investigation immediately unveils a disconcerting truth: “The Navidson Record” is a fiction within a fiction, only existing within Zampanò’s imagination. As they continue learning more about the house and its supposed author, both Truant and the reader are left questioning the author’s intentions as they engross themselves in his expansive narrative.

With three separate storylines running through nearly every chapter, “House of Leaves” constantly runs the risk of being crushed under the weight of its ambitious story. Fortunately, Danielewski handles each plotline with enough time and depth for each one to remain engaging and essential to the overarching narrative. Zampanò serves as both the world-building narrator and a source of relief from the ever-present tension in Johnny’s and Navidson’s segments. Whereas the horror genre often tries to keep the reader feeling on edge and close to the action at every moment — which “House of Leaves” accomplishes with the other characters — Zampanò’s academic perspective and frequent digressions keep the terror at bay while still progressing the story.

But these sections eventually lead back to the Navidson house as Zampanò describes the events of the film. His scholarly voice is soon drowned out by scenes of the Navidson family and the foreboding tension that fills the house. Early chapters present these sections as a more traditional horror story by focusing on actions and dialogue in the present rather than the studies that follow. Zampanò’s ordinarily broad view begins to zoom in on individual moments. However, as the house begins to morph, the text follows suit.

Pages change to match the characters’ surroundings. A narrow hallway manifests as a collage of differently formatted paragraphs that run across multiple pages, all of which describe completely different topics. Likewise, staircases appear as text winding down a page, whereas narrow crawlspaces are represented by paragraphs being slowly crushed until individual words struggle to stay on a single line.

The Navidson plot provides an excellent contrast to the Zampanò segments by thrusting readers directly into the depths of the house. The story zooms in so close to the horror that its pages begin to show only one sentence or a single word, capturing only a moment of silence and suspense. These scenes provoke the creeping suspicion that this silence can instantly erupt with a single turn of the page. But just as easily as the reader is drawn into the house, the footnotes written by Truant snap them out of Zampanò’s fiction and back to reality, serving as a reminder that the true mysteries and horror exist outside the Navidsons’ walls.

Despite the limitations of the physical page, “House of Leaves” experiments with the literary medium in a manner that results in an incredibly immersive novel. The manipulation of text and constant shifting between distinct formats make reading the book feel like undergoing a deep dive into real-life events rather than a typical horror story.

However, in the 22 years since “House of Leaves” was released, few books have tried to use the medium in similarly inventive ways. Danielewski proved that words alone can create a sense of place, effortlessly engage the reader and deliver a story through countless perspectives. The same could be said for movies, video games and even music, but none accomplish this as seamlessly as “House of Leaves.” The book demonstrates how a single page offers endless possibilities for creative storytelling, allowing authors to emulate unconventional formats, shape words into evocative imagery or accomplish something else entirely.

Despite Danielewski’s masterful use of the medium, there are multiple understandable reasons why most other novelists hesitate to follow his example. Compared to other art forms, literature uses a rigidly consistent means of presentation. Books can describe scenic vistas, imaginative worlds and realistic city streets solely through words on a page, as vivid imagery relies on the reader’s imagination. Suddenly switching to a different format can seem pointless or actively disruptive if handled poorly and leaves less room for the reader to visualize the events of the story.

While this works for the deliberate surprise and disorientation of “House of Leaves,” stories in other genres will struggle to justify similar unconventional storytelling. If an experimental style fails to benefit the story, the reader will only view it as a cheap gimmick and a hindrance to the rest of the book.

Even “House of Leaves” suffers because of its nontraditional writing at a few points. While the use of text to replicate movement is incredibly effective in most cases, its presence in some of the book’s mundane and exposition-heavy scenes — especially those focusing on Zampanò — turns ordinary scenes into an unnecessary eyesore. Additionally, the split focus between three storylines with radically different pacing and tones works surprisingly well for the most part, but the early segments of Truant’s story that focus on his everyday experiences with sex, drugs and alcohol initially seem irrelevant to the overarching narrative. His slow start and seemingly inconsequential anecdotes eventually pay off, but first-time readers will likely be tempted to skip his interruptions without realizing their later significance.

Any author that attempts to experiment with literature is undertaking a monumental challenge. Books rely on their lack of visuals to incite the reader’s imagination, so a novel that intentionally works against this quality must produce outstanding writing, clever subversions of the medium and a story that can only be told through prose. “House of Leaves” is worth reading even two decades after its release because it surpasses these requirements. If the Navidson house and the world surrounding it were to ever be adapted into another medium, they would inevitably lose too much of what makes the original novel a modern masterpiece. While the lack of similar works makes sense, more authors will hopefully consider ways literature can explore concepts that would be impossible to depict elsewhere.