Every year, I make new Spotify playlists for each new month, semester, summer and event. They’re often a combination of new songs I’ve discovered during that time, old ones I’ve re-discovered and classic, old-faithful favorites that pop up repeatedly. I didn’t always make time-bound playlists, but I’m glad I started. Shuffling the same playlist of “liked songs” just isn’t the same as being transported back to a specific moment or era in your life with even more specific places, people, outfits and smells attached to it.

For instance, when I listen to my “semester 1 2019” playlist on Spotify, a concrete image comes to mind: I’m sitting on the bus on a rainy day, in the left window seat, on my way home after a day at uni. It’s my first year, and I’m buzzing with the newness of everything. I already have so many readings and assignments piling up, but the stress of that comes nowhere close to the thrill of being at university in the first place, the one thing I’d been counting down to since I’d started high school over five years ago.

There’s one specific album that I listened to on repeat in my first semester: “Bad Habits” by NAV. It has absolutely no correlation in theme or subject matter with my first semester at university, but it’s so special to me because it was a part of my experience. Despite the hate NAV gets, “Bad Habits” was one of the first rap albums I’d enjoyed the whole way through, and the first one I hadn’t listened to because my brother or friend or boyfriend had recommended it to me. It was entirely on my own terms, just like my university experience.

Further along in my music timeline, I remember the beginning of the pandemic in visceral stills, like a movie. Tracks from my “semester 1 2020” playlist appear like a montage: “nosering” by brakence plays while I go for my government-approved daily walk during my state’s first lockdown, “A Kiss” by THE DRIVER ERA plays while I make whipped coffee in the middle of a Zoom class and “Rosyln” by Bon Iver and St. Vincent plays while I watch “Twilight” for the second time this week.

These songs don’t mention or represent anything related to the memories themselves, but because I listened to them so often then, I can’t help but visualize this film reel of moments that I can feel and smell and see so clearly. So why do we attach such strong memories to songs? Why is it that human brains seem hard-wired to remember particular days and events in correlation to music?

In an article by Tiffany Jenkins of BBC, Jenkins described this experience as “hearing a piece of music from decades later and [being] transported back to that particular moment, like stepping into a time machine.” She explained that the brain is constantly storing information, consciously and subconsciously — but it’s harder to retrieve information than it is to store it. Jenkins explained two different kinds of memory, implicit and explicit. Explicit memory is exemplified by a deliberate recollection of past events. For example, mentally asking and answering a question (“what did I have for breakfast this morning?”) is explicit memory at work. Implicit memory evokes feelings and the sense of a moment, which the unconscious psyche absorbs more easily. This makes it more long-lasting, but harder to put into exact words (like, “I had oatmeal for breakfast”). Explicit memory, Jenkins explained, is damaged by conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, where implicit memory will linger. The music follows a rhythm, which makes memories more likely to stick in our implicit memory (which is why you sing the alphabet to remember what letter comes next!)

Psychologists call this phenomenon the “reminiscence bump.”’ This term refers to older adults who remember more details about their youth and adolescence than the rest of their lives. Jenkins explained in her article that this “bump” in memory occurs because this period is when individuals often try new things, meet new people and become independent. This exciting time in life is engrained into your implicit memory because, as Jenkins said, “everything is new and meaningful.”

While I’m not in my 60s, when I read this, my jaw dropped a little. It was like these psychologists were with me on the bus my first year! Somehow, they understood exactly how I marveled at this new phase of my life, at my new classes and heavy textbooks and confusing bus timetables. While this isn’t a true example of the impressive extent of this psychological phenomenon, it was a taste of the intense nostalgia of associative memory.

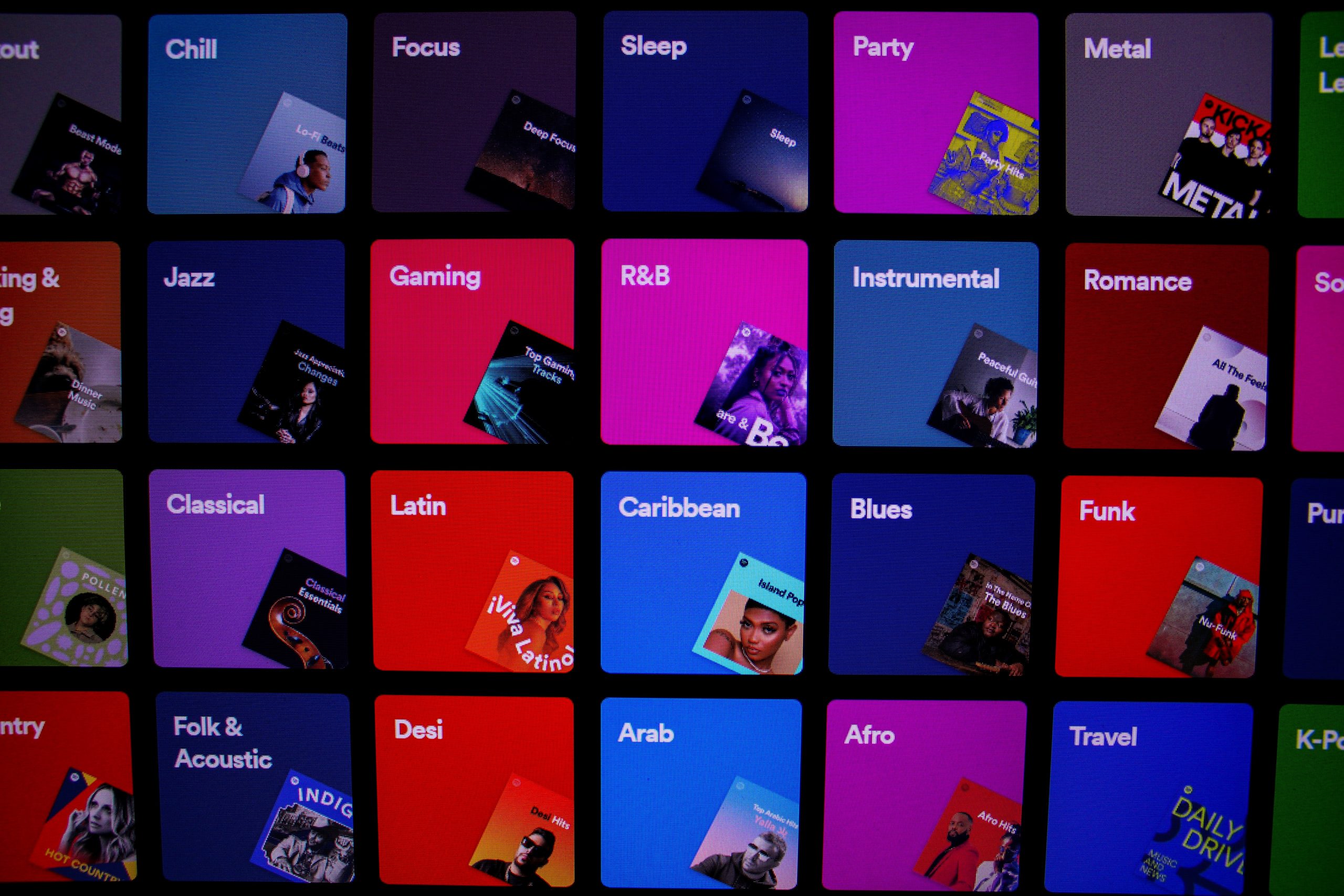

Enter Spotify. Music streaming giant, and implicit memory experts. According to an article by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Spotify bought a firm that studies “music intelligence” to better curate playlists, focusing on mood and feel rather than genre or artist. Many people praise Spotify’s unique access to listening habits to curate personal playlists for all kinds of emotional atmospheres. Spotify also offers a wide library of its own mood-based playlists, including “Confidence Boost” and “Alone Again.” However, critics may agree with Liz Pelly’s view that Spotify merely uses this emotion-focused approach to attract customers and exploit their data for marketing deals. Their slogan, “music for every mood,” certainly supports this.

Ultimately, Spotify has successfully ingrained itself into my memory, whether I consciously realized it or not. It’s now home to the soundtrack of my adolescence, and its design makes it easy to get nostalgic, with each monthly playlist being just a click away. When Spotify briefly went down recently, it was clear their users were both deeply upset and deeply attached. User @laurwanderland tweeted that they would “personally become lethal” if they lost the seven years of curated playlists in their library due to the outage, and @chloefisher1999 begged Spotify to return, declaring that she needed their “curated playlists for every single emotion.”

The playlists I’ve curated (from “summer 20/21” to “quarantine 2” to “moving out with my high school sweetheart”) and the songs I’ve found through Spotify’s intensely accurate algorithms have woven their way into my most precious memories. When associative memory pairs with Spotify’s design, I can listen to the same playlist I listened to in my first semester of university, or during my senior year of high school, and be flooded with memories. These memories are treasured even now and will only become more valuable over time. Based on my playlists so far, I think my actual reminiscence bump is going to be a banger.