I want to preface what you’re about to read with a bit of a warning: Junot Díaz’s piece in The New Yorker, “The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma,” explores childhood trauma, rape and suicidal ideation, so proceed with caution if you choose to read it.

But, if you are able to read about those topics, you definitely should continue and read Díaz’s piece. In doing so, and in participating in a conversation about it, you help to serve Díaz’s purpose for writing it: breaking the silence.

With the #MeToo movement encouraging survivors of sexual assault to come forward, it seems society is moving in the right direction in terms of starting a conversation about rape and sexual assault. Still, the conversation seems to often leave out male sexual assault. Especially for men of color, society seems to keep quiet about the issue, and in turn, quiets men who have been victims of sexual assault.

Díaz’s piece addresses the issue of masculinity and his Dominican background in how they kept him quiet about being raped as a child. He writes, “‘Real’ Dominican men, after all, aren’t raped. And if I wasn’t a ‘real’ Dominican man I wasn’t anything. The rape excluded me from manhood, from love, from everything.”

His fear of not being a “real” Dominican man demonstrates a cultural and societal silence imposed on men — Díaz kept quiet for so long because he was trying to fit into an idea of manhood that he believed being raped precluded him from. In doing so, he promoted silence and prevented himself from becoming a relatable voice for other survivors.

Díaz’s piece opens with a story that relates why this is such an important topic of discussion. Addressing a fan who came to a signing, Díaz expresses his regret for not answering the fan’s question when they asked if he was a victim of sexual assault, since the topic comes up so frequently in his books.

After having once repressed his past, Díaz now starts The New Yorker piece with an apology to that fan — and an admission of his childhood trauma. This coming out, so to speak, is important precisely because of the situation in the beginning of the piece. Survivors of sexual abuse, and others who have faced other types of trauma, find reassurance in knowing they are not alone.

Díaz gets to the importance of breaking the silence in the beginning of the piece. He says, “We both could have used that truth, I’m thinking. It could have saved me (and maybe you) from so much. But I was afraid. I’m still afraid — my fear like continents and the ocean between — but I’m going to speak anyway, because, as Audre Lorde has taught us, my silence will not protect me.”

The idea that silence does not protect is a powerful one, but a difficult one to overcome. Understandably, many anxieties can keep a survivor from coming forward, as they did with Díaz. For men especially, preserving masculinity becomes a major worry. But in coming forward, Díaz takes the brave step to clear a path for other men to come forward, to break the silence.

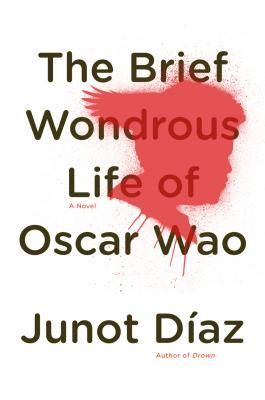

As an author, Díaz is not entirely silent about the issue of sexual assault. His Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” contains allusions to characters having been raped or sexually assaulted.

The novel also bears resemblance to Díaz’s life, as it is set in New Jersey and sees characters attending Rutgers, as Díaz did himself. Despite those connections, Díaz had remained silent about his trauma until his piece in The New Yorker.

Breaking the silence seems to have stirred the same desires in others to speak out, or at least build the conversation. Response to the piece has been overwhelming, with floods of articles from news and media outlets praising it.

Time referred to the piece as Díaz’s “emotional story.” NBC News called it “moving” and “heart-wrenching.” And the articles aren’t wrong. Díaz’s expertise with prose allows him to take the already emotional topics of rape, depression and suicide, and elevate them to something so profoundly moving.

Other readers have also voiced their opinions on Twitter, adding to the praise of Díaz’s piece. Tweets include “Junot Diaz is saving lives with that essay” and “This is a shattering piece of writing.” But amongst the one-line reviews, there are some criticisms, primarily surrounding the treatment of women Díaz reveals.

Díaz describes a relationship with a woman he calls “Y—” to whom he was engaged and in love with. He says, though, “And because I ‘loved’ her more than I had ever loved anyone, and because I had revealed to her what I revealed about my past, I cheated on her more than I had ever cheated on anyone.” The way Díaz hurt Y— made some on Twitter reflect on how men respond to trauma.

One tweet in a thread about how it seems many men cope (or don’t) with trauma reads, “Like so Diaz put this woman through the ringer of trauma & then made a book about it that immortalized into art what he learned through the pain he inflicted on her. But I know his name & not hers.”

A response to that tweet acknowledged the importance of the piece, with a caveat, saying, “I do think Junot Díaz’s @NewYorker essay about childhood sexual abuse and a lifetime of post-traumatic struggle is poignant, groundbreaking, and heart-shattering — but this perspective, about all the women sacrificed for one man to heal, is a necessary corollary to it.”

I do think Junot Díaz's @NewYorker essay about childhood sexual abuse and a lifetime of post-traumatic struggle is poignant, groundbreaking, and heart-shattering — but this perspective, about all the women sacrificed for one man to heal, is a necessary corollary to it. https://t.co/ZRbVD5jhLN

— Roma Panganiban (@romapancake) April 10, 2018

While Díaz doesn’t make a significant portion of his piece about solving problems with how he treated loved ones, particularly women, he does say something that leads to the idea. He writes, “I don’t hurt people with my lies or my choices, and wherever I can I make amends; I take responsibility.”

It does not seem that Y— received any of those efforts to make amends, considering Díaz says they have not spoken since their breakup, though an effort to make amends in other parts of his life is important, and should have perhaps been emphasized more.

While the issue of how women were treated by Díaz and other men who have experienced trauma is an important one, it’s still important to acknowledge the significance of Díaz’s piece and how it breaks the silence on an issue many face but don’t come forward about.