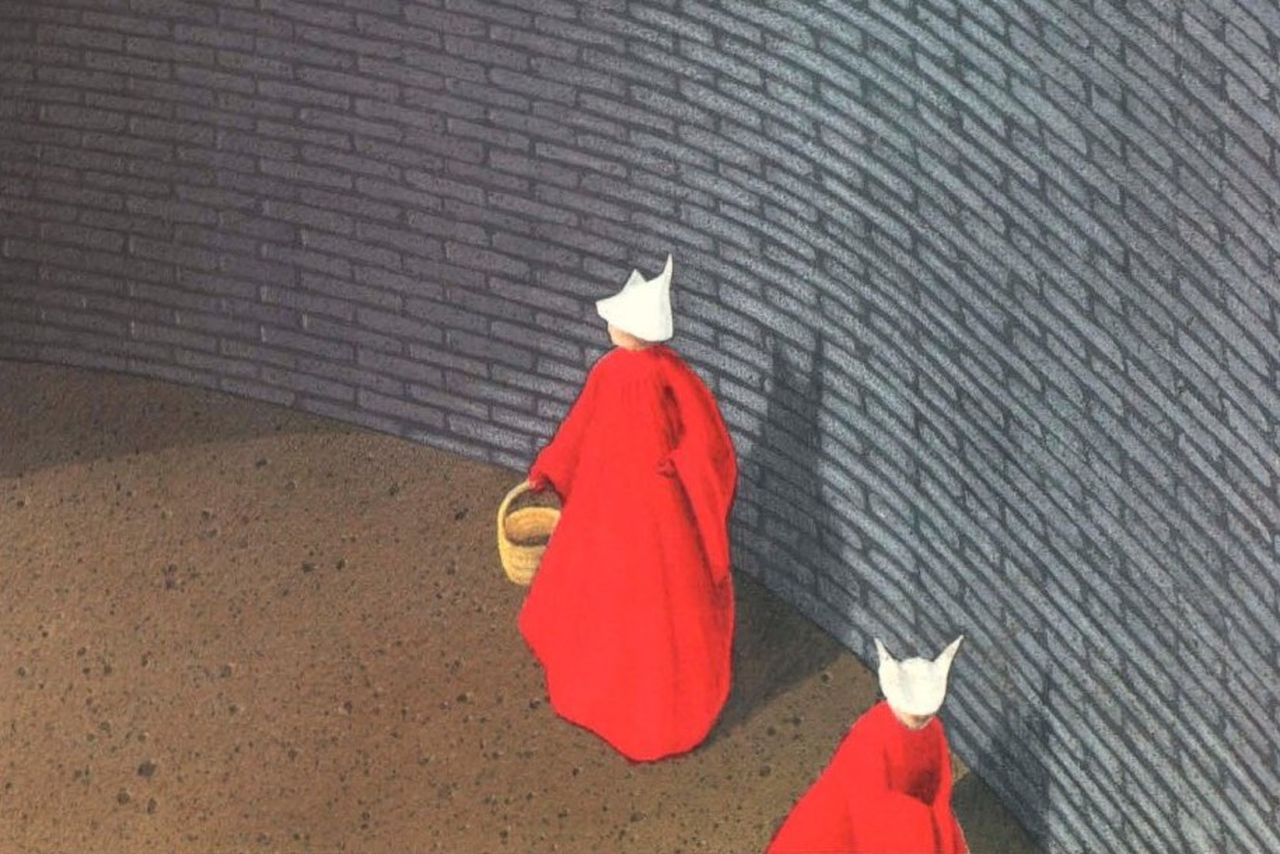

The Handmaid’s Impact

Hulu’s new original series might be breaking streaming records around the world, but Atwood’s dystopian tale has a subtler message that gets easily lost.

By Alicia Drier, Roosevelt University

When I first read Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” in 2007, I was a freshman at a Christian university who was quickly more willing to believe in the innate good of anyone over the bad.

And while I regularly quoted Abigail Adams, Eleanor Roosevelt, Susan B. Anthony—and truly believed in the importance of equal rights for women throughout the world—I was initially more fascinated than terrified at the end of Atwood’s novel.

A decade and two degrees later, I have come to know women who attend family voting meetings, in which the father of the household will tell everyone what their ballot should look like in the next election. I have been called a slut and a whore by men for the way I dress—and been reminded, when I seek to respond, that “Boys will be boys.” I have held my best friend while she cried when she found out she was going to have a girl, not because she hated the thought of being a mother, but because she feared what the future of her daughter in the world today might be.

This is why I can’t stop thinking about Hulu’s premiere of “The Handmaid’s Tale.” And considering the timeline of Atwood’s story, you wouldn’t think this was necessarily true. Atwood first began work on the story of Offred and the Republic of Gilead in 1984, years before I was born. At the time, Atwood was living in a wall-divided Berlin. In a March 2017 “New York Times” article, she explained of this period, “I experienced the wariness, the feeling of being spied on, the silences, the changes of subject, the oblique ways in which people might convey information, and these had an influence on what I was writing. So did the repurposed buildings. ‘This used to belong to . . . but then they disappeared.’ I heard such stories many times.”

Atwood goes on to write, “One of my rules [when writing] was that I would not put any events into the book that had not already happened…nor any technology not already available. No imaginary gizmos, no imaginary laws, no imaginary atrocities. God is in the details, they say. So is the Devil.” Similarly, Atwood said to star of the Hulu show, Elisabeth Moss, “Everything I wrote in that book was happening at that time, or had already happened. It just wasn’t happening in America.”

This obsessive attention to truth-like details is what remains at the core of the new adaptation’s fear factor for me. It’s one thing to bring to life a story about a minority group progressively losing personal rights to work, family and their bodies, but it’s something completely different when the audience can’t remove themselves from the picture on the screen. On the evening of April 26, after bingeing the first three episodes and then trying to go to bed, I had dreams in which I’d go to my job the next day only to find out that all women had been let go, that I no longer had access to my bank accounts and forms of income, that I was no longer considered a citizen of the United States.

As producer Bruce Miller explained in response to his vision for the show, my reaction was exactly his hoped-for result: “Our version needed to be unflinching if it was going to be successful. If it isn’t real―if you can say, ‘Oh, that’s not the real world’―then it’s less scary. The more it feels like the real world, the scarier it becomes, at least to me.”

In the context of the 2017 “Handmaid’s Tale,” this banter with modern-day imagery is one of the show’s most important strengths. According to “Buzzfeed” writer Kate Aurthur, “Regardless of one’s political stripe, there’s an instability and a chaos these days, a feeling that anything can happen. Such is the mood of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale.’ There aren’t one-to-one comparisons between Trump policies and the show’s vision of Gilead, but the book and its imagery have become powerful symbols unto themselves. On Jan. 21, as people marched around the world for women’s rights, some held signs that read, ‘Make Margaret Atwood fiction again,’ ‘The Handmaid’s Tale is not an instructional manual’ and ‘No to the republic of Gilead.’”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJTonrzXTJs

It’s true that “The day after Trump was elected, sales of Atwood’s book increased 200% from the year before. It shot to the top of Amazon’s bestseller list, alongside George Orwell’s ‘1984’” (read more about that here). And it’s very true that this Hulu show is riding heavily on the coattails of the post-Trump human rights uprising.

But I don’t want to view “The Handmaid’s Tale” as just another anti-Trump rant. More than fear or popularity or current politics, I’ve kept coming back to “The Handmaid’s Tale” over the past ten years for its timeless message of hope. As a dystopian text, it warns its viewers of what could come to pass, not what is meant to be. And the story’s mantra of “Nolite Te Bastardes Carborundorum” encourages its audience to not let that future come true.

In my pessimistic graduate student years, I still have a little belief that humankind can pull through anything. Atwood’s world of warning helps me constantly keep that in mind.

Re: “It’s one thing to bring to life a story about a minority group progressively losing personal rights to work, family and their bodies, but it’s something completely different when the audience can’t remove themselves from the picture on the screen. ”

You can only feel anything when it’s somebody who looks like you? Maybe if more people could empathize with the pain of people who do not look like them we wouldn’t have so many problems.

[…] source source […]