“Today I want to encourage any of you who still wear your good-girl shoes to hang them up.”

As a proud and passionate owner of good-girl shoes in every style and color, these words from Kate White jarred me to my very core. I entered the hallowed halls of The New York Times building on 41st Street to hear White, the former editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan and acclaimed novelist, speak on an intriguing topic: “Interview Prep: How to Be the Gutsy Girl That Gets The Job.”

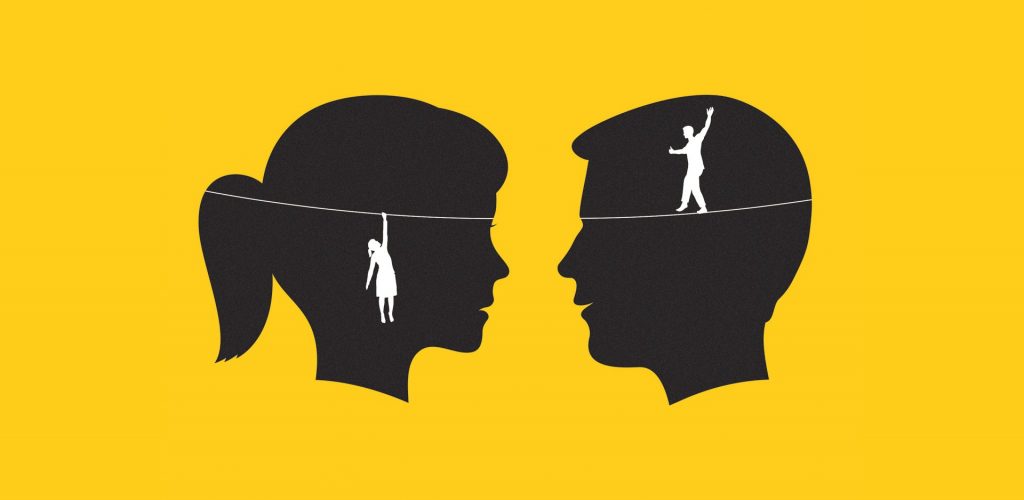

I left enlightened and yet paradoxically more confused than ever before, as I was unwittingly thrust into a raging internal conflict: Can I be nice and still be successful?

Perhaps the very foundation of this debate has to do with how “nice girls” are valued differently than “nice boys,” and how being nice affects one’s efficacy in an internship or job. Fortunately, there exists ample literature on the topic.

Unfortunately, the articles and books seem split down the middle as to their take on this pressing question, leaving me with one deeply unsatisfying drawn conclusion: In order to have success in the workplace, one needs to take risks and throw away the “nice” persona girls have been instructed to carefully maintain throughout their lives.

To those, like me, who have cultivated over the years a very dependable and unyielding nice-girl attitude, this comes as a weighty blow. Not only does this mean that this strictly-adhered-to behavior will not aid in future successes, but it will actually become a hindrance to attaining one’s dreams and aspirations.

This does not mean, however, that every nice woman should transform herself into a snarling, ruthless career-monger. Rejecting the nice-girl label in the workplace does not mean that one cannot, or should not, lead with empathy and understanding.

It means that women need to empower themselves to break the mold, ask for forgiveness and not for permission, take risks and even get in some trouble because these actions breed success.

Jill Filipovic hit the nail on the head with her article in The New York Times, entitled “The Bad News on ‘Good Girls.’” She frankly designates this internal dilemma of taking risks versus being good as an inherently female quandary. She argues that boys, from their earliest days, can engage in more aggressive and unpredictable behavior because their parents not only tolerate but expect this behavior from them.

Parents and adults at large seem to conversely encourage girls to follow the rules and do as they are told, a message they take very much to heart. Filipovic writes that girls generally do better in school than their male counterparts thanks to their good-girl instincts, but this becomes a disadvantage later in life “in high-earning fields like technology that value assertiveness and creativity and entrepreneurial roles that reward risk-taking.”

Filipovic emphasizes how these mixed messages can eventually have even more serious ramifications. “Now-pervasive ‘Girl power’ messaging declares that girls can be anything they want. But in practice, the more subtle rewards for compliant behavior show girls that it pays to be sweet and passive,” Filipovic said. “The sexual harassment revelations that have come to light over the past few months show just how dangerous this model can be.

Yet Fran Hauser writes that these sexual harassment stories present the occasion for a necessary shift in leadership style, which women can pioneer. In an article for Refinery29, Hauser, a startup investor and adviser, writes, “We have come to a place in the world where being tough, short-tempered, and having a lack of empathy for others represents power and leadership.”

For Hauser, fitting into a not-nice leadership role felt uncomfortable and phony. Instead, she elected to embrace her innate kindness and let it fuel her success, which enabled her to achieve successful positions such as president of Digital for Time Inc.’s Style and Entertainment Group. She tells a story of an intimidating sit-down with an employee while working at Coca-Cola Enterprises when she had to deliver negative feedback. But instead of approaching the situation with guns blazing, Hauser took a good girl’s strategy and calmly talked it out by identifying the root of the problem and selecting a solution.

“The truth is, you can play the role of the big bad boss, play into the labels and get the corner office, or you can be your authentic, kind, unique and ambitious self and also get the corner office,” Hauser said. She feels so passionately about this subject that Hauser released her book, “The Myth of the Nice Girl,” in April 2018.

The messages of all these various talking heads whirred around my brain as I listened intently to Kate White spew wisdom to a room of eager young girls. She told a story about a woman she had met who designed bags. Her bags were about to be showcased, and after giving them one last look she realized they seemed very plain. In a moment of unconventional inspiration, the woman snipped out the tag from inside the bag and sewed it onto the front. That woman was none other than Kate Spade, and she popularized this style and became a household name in design.

“The breakthrough ideas break the rules,” White said.

Inspired by White’s message and cognizant of its relevance to my imminent future, I bought her newest book: “The Gutsy Girl Handbook: Your Manifesto for Success.” White discusses the importance of exuding confidence and excellence, asking for what you want and pitching crazy, bold ideas. All of this resonated with me, but made me wonder if being gutsy and being nice are truly mutually exclusive ideas.

The key to compromising a good girl attitude and a gutsy girl drive, I believe, lies in redefining what “nice” or “good” means in the workplace. If “nice” means being a pushover and letting someone else take the credit for your killer idea, then this will undoubtedly start to thwart your upward progress and your perceived value in your employer’s eyes.

But if being a nice girl or a good girl means taking the time to be relational with subordinates, communicate effectively and emote when emotion is strong, then girls like this can absolutely still find success, think outside the box and be gutsy. In fact, nice girls could be just what the workplace needs right now.

Kate White, I’ll hang onto some pairs my good girl shoes for now because I know I can still be gutsy while donning them. Once women reject the compliant behavior associated with being nice and use their empathy to their advantage in the workplace, they can invoke a powerful revolution across many diverse fields. Their male counterparts could even learn a lesson or two from their good and gutsy leadership.