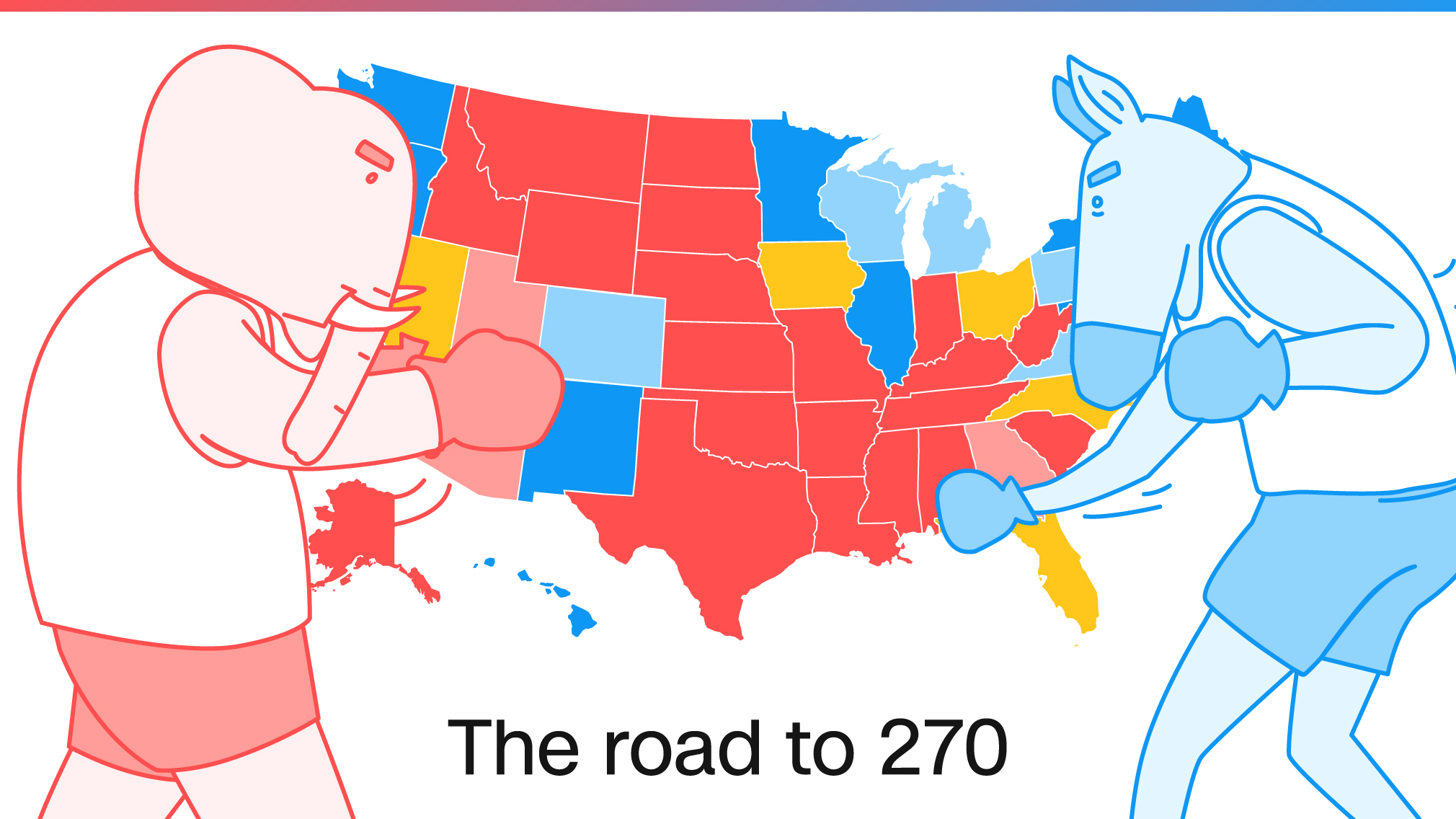

For the second time in the last three non-incumbent presidential elections, a republican candidate won the White House without the popular vote.

In fact, Donald Trump won by a rather comfortable margin of 58 electoral votes, despite almost 800,000 more people voting for Clinton nationwide.

This has left many citizens feeling disenfranchised and wondering why the Electoral College is in place at all, especially when it seemingly gives small groups of voters the power to decide national elections. It’s a complicated system with several problems, but so are most of the alternatives. To understand the Electoral College, it is necessary to first understand its origins and purpose.

How It All Goes Down

The EC was written into the Constitution in 1789 under Article 2, establishing that each state would choose the number of Electors equal to its seats in Congress (no state can have less than three). These Electors, usually being knowledgeable of current political events, would then cast their ballots for president unbound by public opinion.

In the original vision of the EC, the common people didn’t directly vote for the president; instead, the Electors were chosen by the state legislature. But in modern practice, Electors are chosen through popular vote and are typically required by law to cast their Electoral ballots in correspondence with popularity. Whichever candidate is the most popular takes all the Electoral votes for the state.

The considerations of the founders were two-fold.

First, they worried that a charismatic demagogue would be able to manipulate the opinions of the general public, and they wanted to develop a system that ensured only someone qualified to be president was elected. Federalists of the time didn’t trust the citizens to make the right decision, so the Electors would act as a check on irresponsible voting.

Distrusting the public may have been warranted at the time of the Constitution’s drafting. Most of the population was uneducated, and information didn’t reach the rural parts of the country as quickly as it does on the internet. Times have changed though, as today over 80 percent of modern Americans finish high school and over 40 percent have a college degree.

“It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice.” –Alexander Hamilton

Second, the founders wanted to ensure that larger states with massive urban areas couldn’t impose their will upon lesser populated states. Fearing that cities might put their own interests over the needs of the nation, the founders wanted to give leverage to the disadvantaged.

This leverage manifests in the potency of each vote. For example, Wyoming’s three Electors represent a voting bloc of roughly 250,000 people. This means about 83,000 people are equal to one Electoral vote. In California, their 55 Electors reflect 12.5 million voters, meaning that it takes over 225,000 California votes to equal the same electoral vote.

Leverage is one thing, but this wide of a leeway is cause for concern — Trump won by 58 electoral votes, how many millions of people had to be displaced to get to that margin?

My contention is that the public is now trustworthy enough with its own civic duty, and it deserves a more accountable form of representation. Known alternatives, however, can be just as cantankerous.

Are There Really Any Better Options?

A direct popular voting system has been advocated by opponents of the EC, and at first this can seem like the best option. But consider the undertaking of a recount, remember how convoluted Florida was back in 2000?

A discrepancy of 1000 votes took over a month to sort out before Bush was declared president by a split Supreme Court decision (5-4); the controversy of that election is likely to be in American history books for hundreds of years. Apply that scenario to 120,000,000 national votes, with each county having their own recount stipulations — the time and bureaucracy it would take to achieve a national recount is nauseating.

A popular vote would also open the floodgate of the dreaded campaign advertising, instead of containing it mostly to the swing states. Can you imagine the implications that national campaigns would have for big spending in politics?

The parliamentary method is another seemingly effective approach to government. In this system, the executive branch is headed up by the majority legislative party, and they generally hold enough seats in Parliament to pass the laws they wish.

The minority parties in a parliament have the job of criticizing the majority and advocating their better ways of doing things, but they do not hold enough power to gridlock the law-making process the way U.S. legislators do.

However, a prominent criticism of the parliamentary system is that the prime minister is not elected by the people, but by the legislature under influence of the majority. The PM can also lose his/her office if they lose their seat in parliament, despite being popular nationally. This system also leaves no effective check on legislative power, and changing the U.S. over to this would require changing the country on a fundamental level.

Balancing Out the System

Perhaps the best solution for the U.S. is to not change the Electoral College much at all. What if instead, Electoral votes were awarded by state, proportionate to the popular vote (and not winner take all)?

Furthermore, what if Electoral votes went by congressional district?

Though Gerrymandering could be a kink in this model, if the U.S. is going to fix its election process, it might as well fix it right the first time. The technology is available to have fairly drawn, non-partisan districts, eliminating Gerrymandering permanently.

The Electoral College has its flaws, but that doesn’t mean it should be scraped completely. With some simple amendments and time to develop, it’s very likely that it could be perfected. This is the 21st century; it’s about time our system of government reflected that.