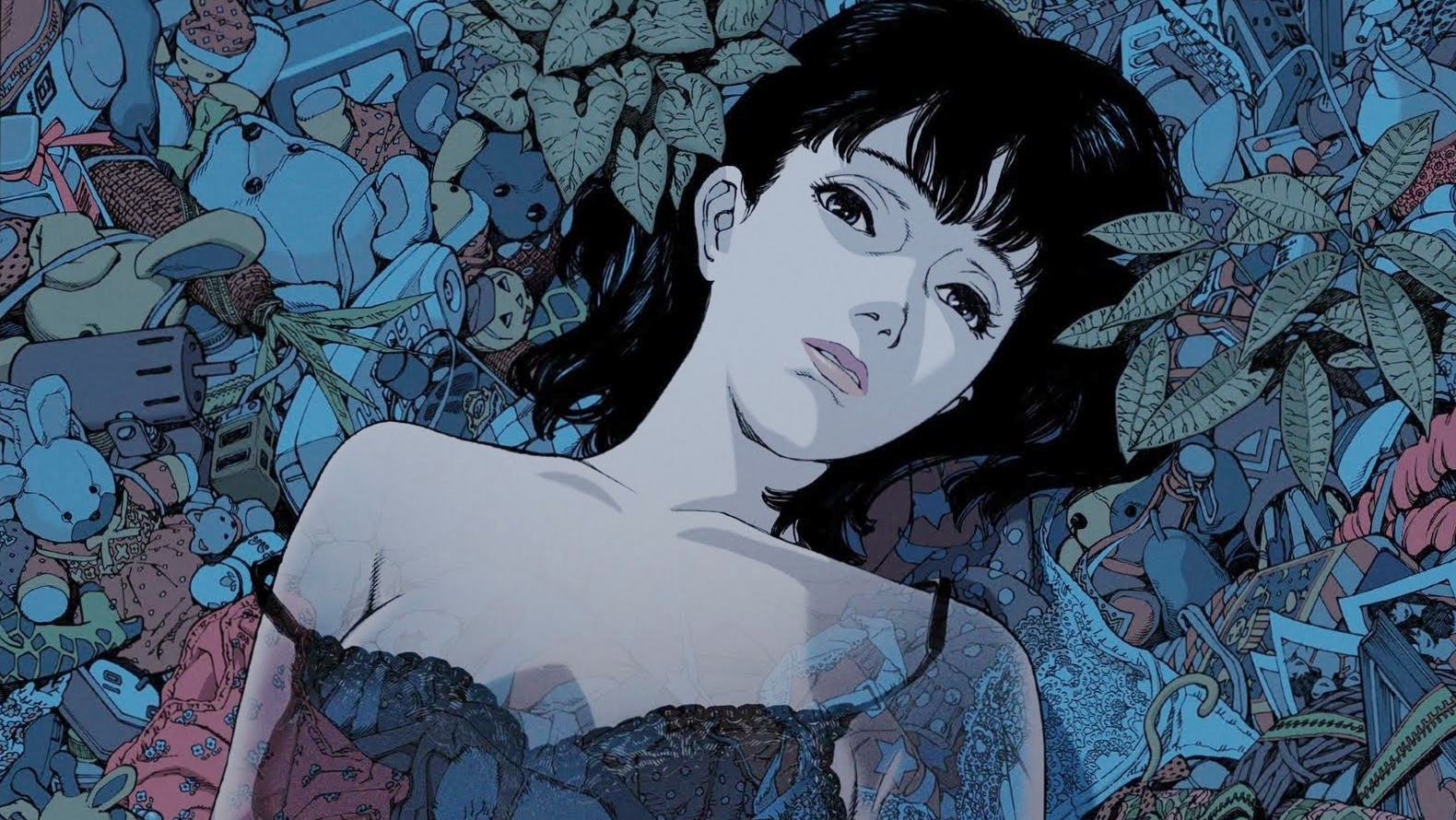

Spirited Away

Hayao Miyazaki was arguably the most notable name in the anime industry even prior to the turn of the century thanks to such iconic and creatively captivating masterpieces such as “Castle in the Sky” and “Princess Mononoke,” but he eternally cemented his legacy as a magician of imagination following the release of the spellbinding “Spirited Away” in 2001.

A deceptively simple coming-of-age tale, the film follows the young, stubborn Chihiro as she’s thrust without warning into a fantasy world of spirits, witches and surreal magic, forcing her to gradually evolve beyond her close-minded view of the world in favor of embracing independence and initiative. Miyazaki’s signature unrivaled creativity and masterful utilization of animation is on full display here, detailing a lush, vivid world that could only exist through illustration.

Such sequences as a majestic dragon’s scales shattering into the sky or a flock of enchanted humanoid paper figures swarming over an endless, crystal blue sea are sequences that could only realistically come to life with the intended charm and expression if done through animation, not to mention such eccentric, surreal character designs such as the haunting witch Yubaba or the iconic, lonesome No Face. To attempt to emulate such attributes in live action would mean an astronomically high budget for costume and set design, special effects and editing. Even with those resources, it’s unlikely that Miyazaki’s vision could directly translate to a live action setting as fluidly as it does through 2D animation. The animated nature of “Spirited Away” allows the audience to directly immerse themselves in the striking, awe-inspiring imagination of its legendary director with no filter to hinder the creative process, resulting in a considerably more charming, captivating experience as a result.

The only two-dimensional animated film to ever secure the Oscar for best animated feature, Miyazaki’s magnum opus demonstrates the power and specificity of animation more effectively in some single scenes than other works in the same medium approach during their entire duration. It’s a quintessential viewing experience, not solely for animation efficianados, but also for anyone with even a remotely passing interesting in filmmaking. Miyazaki’s irresistibly intricate world will capture your awe and wonder as if you were a child witnessing the world anew for the first time, evoking powerful, emotional imagery that will embed itself in your psyche for the vast majority of your life while embedding a perception of the animated medium as an extraordinary conduit for creativity.

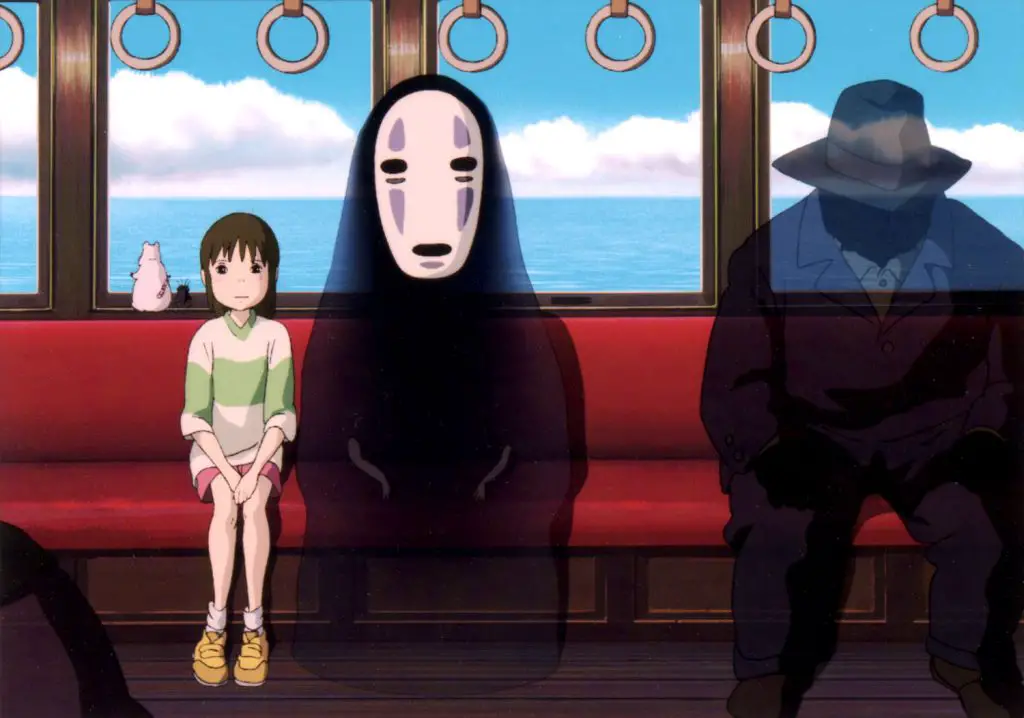

Perfect Blue

If Hayao Miyazaki represents the Japanese equivalent of Walt Disney, then Satoshi Kon could more accurately be compared to Alfred Hitchcock. “Perfect Blue” certainly provides convincing evidence for such a comparison.

Admittedly, this haunting psychological thriller narrative of Mami, an exceptionally popular pop idol turned failed actress, doesn’t appeal to animation’s specificity nearly as strongly as any given Studio Ghibli production; “Perfect Blue” could very much exist as a live action film. However, what it lacks in surreal creativity, it more than makes up for with unparalleled editing proficiency, intricate color symbolism, and an intricate labyrinth of a multi-layered plot that continues to reward repeat viewings.

What is especially harrowing is the film’s social commentary on the danger of obsession with one’s public image, and the partial insanity that comes with trying to maintain an idealized public persona while staying true to one’s flawed and vulnerable self; in essence, a cautionary tale of duality. Considering the film released in 1997, long before the advent of social media which created a mass fixation on crafting a romanticized version of oneself on such platforms, its messages become even more terrifying now that they’re more relevant than ever in the present day, 20 years later. Kon accurately read society’s trajectory like an open book.

A distinct, dynamic editing style keeps the viewer guessing as to what scenes represent reality versus what images are hallucinations witnessed by the protagonist during her descent into insanity. However, sophisticated color symbolism and sound motifs provide enough clues to conceivably track and distinguish the objective from the subjective upon repeated viewings; this, combined with late-story revelations that contextualize earlier, seemingly surreal moments, make “Perfect Blue” a rewarding film to witness multiple times. Kon’s mind-bending thriller may not provide the visual flair of a “Spirited Away” type film, but for those who stigmatize animation for limiting its appeal to children, it provides an example of intricate, mature storytelling that’s rife for analysis and discussion. Just be ready to focus.

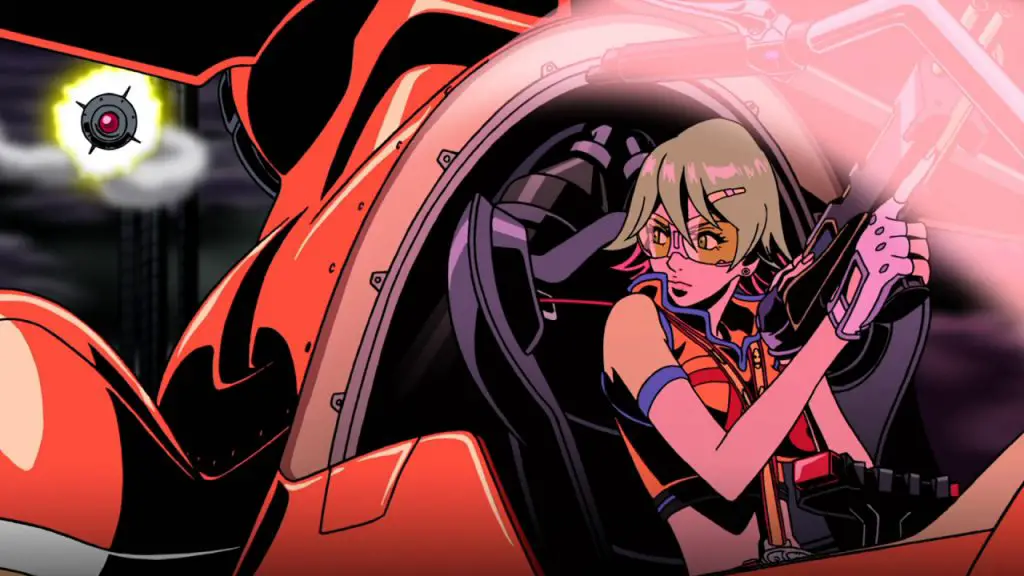

Sword of the Stranger

Let’s make one thing clear: “Sword of the Stranger” is a fantastic action film with a suitably engaging and emotional narrative, but you watch this film for the final fight. That’s not to say it would be wise to simply witness the climactic confrontation on YouTube and skip the additional 90 minutes of context, however.

Masahiro Ando’s seemingly straightforward samurai romp features surprisingly intricate lead characters in Luo-Lang and Nanashi, the former an unrivaled antagonistic combatant looking for a worthy fighter following one too many apathetic fights, and the latter a reluctant master swordsman who keeps his blade perpetually sheathed throughout the film’s duration due to a tragic and unjust past. Though the two fight for opposing armies, “Sword of the Stranger” primarily focuses on building up both their internal conflicts and motivations so that the two may finally unsheathe their katanas in one-on-one combat during the film’s grand finale.

This is very transparent, but the emotional investment in each character is required to provide the confrontation with the necessary stakes and gravitas. These warriors need to feel like titans destined to battle each other, individuals who can only unlock each other’s potential and remedy their emotional distress by fighting under the specified circumstances built up during the movie’s runtime. Of course, if a director opts to pace the story this way, sparks really need to fly during that heavily anticipated duel.

Boy, do the sparks ever fly between Luo-Lang and Nanashi. What follows can only be described as undeniably one of the finest fight scenes in cinematic history that demonstrates the profound and unique impact an animated confrontation has the potential to possess. Everything about this climax is intricately orchestrated to deliver an extremely creative and satisfying payoff to the film’s build-up, including unique staging, expertly mapped choreography and a suitably epic score to accompany the action.

What pushes this fight into the realm of legendary status, however, is the animation itself. Crisp and fluid, yet delivering weighty impact to each blow, a masterful blend of intimate close-ups and longshots distanced from the action, and Nanashi’s scrappy, quick blows contrasted with Luo-Lang’s harshly imposing sweeping movements and hostile facial expressions. Everything about these three minutes of combat fires on all cylinders, crafting a distinct, memorable encounter that bends the rules of reality just enough to feel perfectly at home in the animated medium without breaking immersion.

I watch a lot of anime, but even my jaw dropped for the majority of this fight when I first witnessed it. If you’re after great action, look no further.

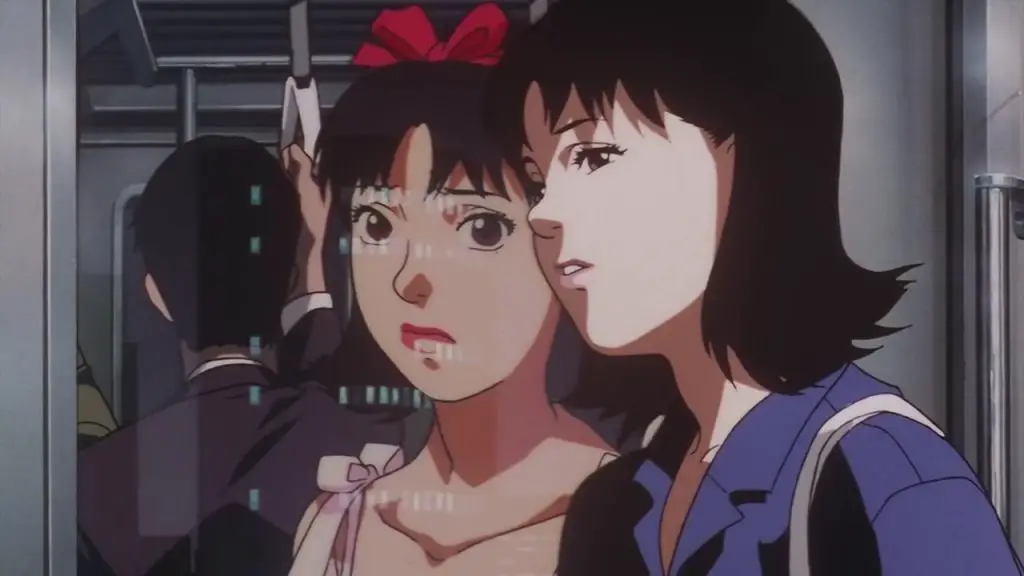

Redline

Watch the first race sequence in “Redline” and try not to have a big, stupid smile on your face by the time the title flashes on the screen. Go on, I dare you.

While “Spirited Away” revels in its visual creativity, “Perfect Blue” perfectly captures the intricacy of a psychological thriller and “Sword of the Stranger” delivers on its promise of epic action sequences, “Redline,” Takeshi Koike’s passion project racing film that took seven years to animate, prioritizes fun and speed over all else.

In this aspect, it succeeds immediately from its opening action scene, accelerating the average pace of its primary duo of characters, J.P. and Sonoshee, as they blister towards the finish line, pulling out all the stops of their modified garage vehicles in order to achieve first place. Along with establishing a competitive rivalry relationship between the two characters that will carry through most of the film, “Redline” takes advantage of its greatest strength as an animated story: pure frenetic energy.

As the racers increase their velocity to impossible levels of speed, harsh action lines appear on the edge and in the background of scenes to give them the illusion of acceleration, with the vehicles themselves vibrating at exaggerated levels of frequency, establishing suspense by illustrating the cars being pushed to their very limits. However, J.P. possesses tricks up his sleeve that few other racers can rely on, including a one-use turbo boost that causes his car to reach impossible levels of speed; when he inevitably uses it during the opening race, the turbo boost erupts J.P. into first place. His exponential increase in acceleration is exaggerated by vertical shots of both the protagonist and the inside of his racer gradually elongating, with specific focus on facial features that indicate maximum velocity, such as tears streaming behind J.P.’s head and lips flapping in the wind.

All these editing flairs serve to create this grand illusion of intense speed that perpetually increases throughout the contest, maximizing the adrenaline produced by each of the film’s racing sequences alongside an increasingly intense soundtrack and accelerated editing style toward the opening’s conclusion. These little touches would be tremendously difficult to successfully emulate in live action entertainment without sacrificing the charm and impact of the film’s visual finesse, most notably the hyperbolized facial expressions and vibrant yet unrealistic movement of the vehicles themselves.

In short, the frantic energy and adrenaline that make “Redline” such a treasure to behold is partially due to it existing within the animated sphere, allowing it to behave very liberally with the laws of physics and reality in order to achieve its intended tonal goal. Not every scene in the film is about generating transcendent levels of speed, but those sequences serve to detail why it works as an animated feature: In an anime format, “Redline” is allowed to bend reality in favor of adrenaline, speed and, most importantly, fun.

Wolf Children

Like “Perfect Blue,” “Wolf Children” isn’t necessarily as important for its visual specificity (though it does have a distinctly beautiful art style) as it is for its rich story and expertly explored characters. Unlike “Perfect Blue,” however, the quality of “Wolf Children” isn’t measured by how many deep philosophical questions it can generate, but rather by how many tears it will inevitably bring to your eyes.

A masterwork of pathos without feeling too contrived or heavy-handed, Mamoru Hosoda’s emotionally stirring exploration of a wolf-human family hybrid struggling to find a suitable place in between two dramatically contrasting worlds epitomizes the type of deeply relatable emotional connections that gave Pixar and Ghibli their claims to fame. Themes such as sibling bonds and rivalries, single parenthood, solitude and the struggle of conformity are thoroughly and efficiently explored throughout a perfectly paced two hour runtime, ensuring that nearly every member of its audience finds something to resonate with, and thus maximizing its myriad emotional payoffs when they do occur.

The significance of “Wolf Children,” however, is in its striking blend of tone that effectively concocts the illusion of a genuine human experience. Scenes of love brutally transition to sequences of tragedy (there’s a particularly moving sequence in the winter), moments of solitude are met with resolutions of camaraderie and instances of a cold, unforgiving urban life are balanced by the neighborly compassion of the film’s second main setting, the countryside.

The narrative understands that real life is never overwhelmed with an abundance of one particular emotion, but rather an amalgam of positives and negatives that shape our everyday lives, and through this tonal cornucopia, it’s able to surprise, empathize and draw the audience’s attention. The characters, particularly Hana, the mother and main character of the film, feel like real people with identifiable pinnacles and low points who admirably strive to improve and find their way in the world, an easily relatable struggle that helps craft these fictional figures into genuine people that the viewer can attach to.

In essence, “Wolf Children” perfectly demonstrates that animation isn’t merely a simpler form of media compared to other entertainment, content to pass off lazy slapstick and shallow narratives as worthwhile entertainment as the general stigma would have the masses believe. Rather, it possesses the capacity to move emotions and inspire hype using unique methods that prove its worth and identity as a separate media platform altogether, evolving the pathos of cinematic storytelling in new directions. Simply put, if you have a heart, “Wolf Children” is a required viewing experience—just make sure to bring a tissue or two.