On June 7, protesters in Richmond, Virginia, brought down a statue of Jefferson Davis. Davis was the first and only president of the Confederate States of America. Richmond was the breakaway state’s capital.

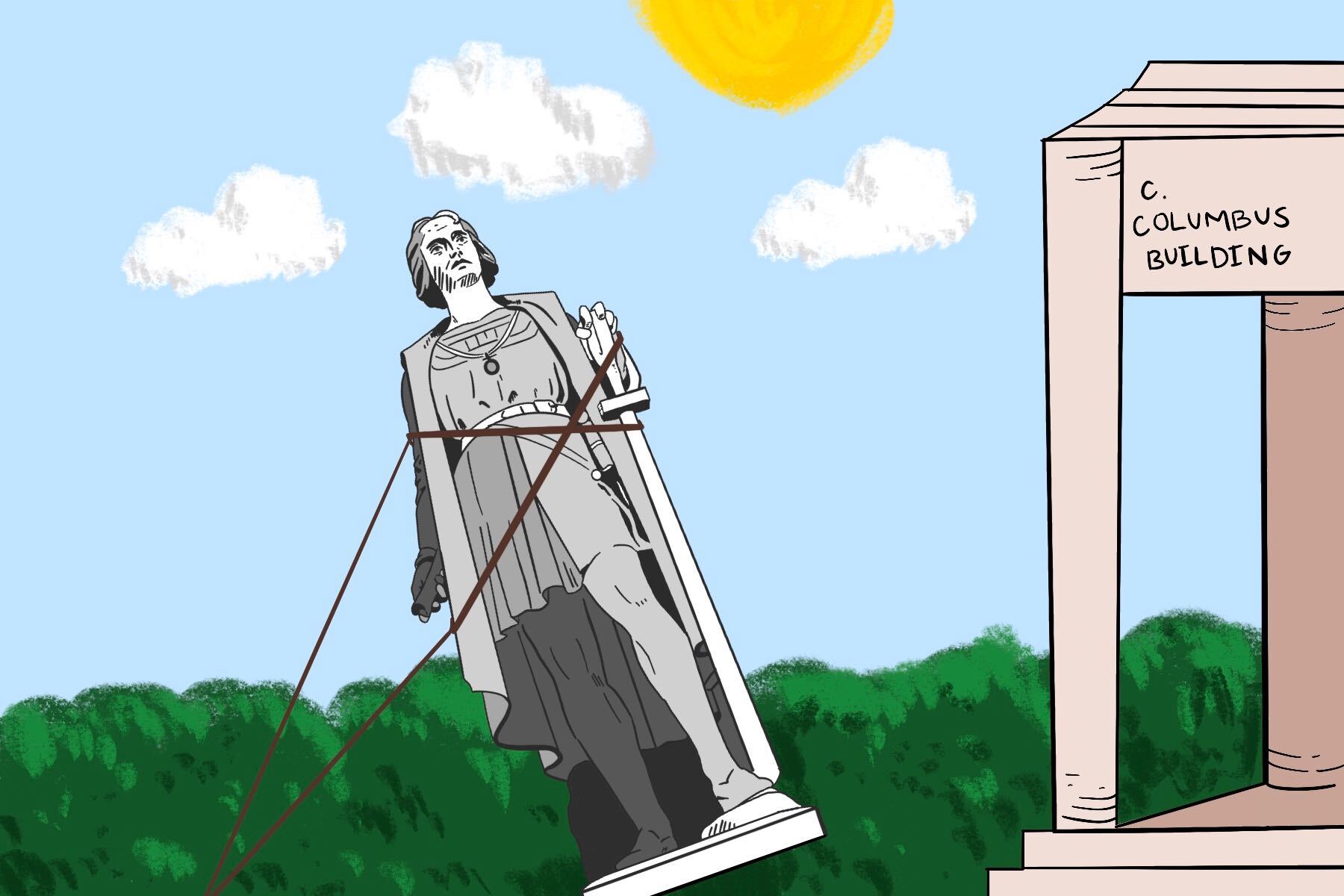

Three days later, protesters in St. Paul, Minnesota, toppled a statue of Christopher Columbus; it was located on the grounds of the state capitol — a stark reminder of the racial callousness that still pervades government at all levels. Mike Forcia, a Native American activist who led the protest, called the statue a symbol of genocide. A defensible position considering, among countless other crimes, Columbus’ enslavement and near-total eradication of Hispaniola’s indigenous Taino population.

The removal of these two statues are not isolated events. They happened within a broader, nationwide movement that was largely motivated by the murder of George Floyd. But tearing down statues of racists is nothing new. In fact, three short years ago, a wave of Confederate monument removals took place in response to the infamous 2017 Charlottesville hate rally. The core belief underlying these acts is quite obvious: Racist oppressors should not be glorified in a public square.

But some contend that this seemingly common-sense insight can be extended to the point of absurdity. In an attempt to demonstrate this, right-wing pundit Jesse Kelly tweeted the following:

“Yale University was named for Elihu Yale. Not just a man who had slaves. An actual slave trader. I call on @Yale to change its name immediately and strip the name of Yale from every building, piece of paper, and merchandise. Otherwise, they hate black people. #CancelYale”

This was likely inspired by a tweet from the previous day — Juneteenth, no less — by far-right author Ann Coulter.

202 years of celebrating a racist, genocidal slave trader is enough. YALE. MUST. CHANGE. ITS. NAME. #CancelYale

— Ann Coulter (@AnnCoulter) June 19, 2020

Both comments were made in jest and meant to parody what they perceived to be poor logic on the part of activists aiming to remove racist statues. But neither are the “gotcha” Coulter and Kelly think they are. There is, in fact, something unsettling about naming an institution associated with power, achievement and prestige after “a racist, genocidal slave trader,” as Coulter puts it. And the impulse to name the school after a more honorable individual is worthy of neither shame nor ridicule.

Whether renaming Yale is a fight worth having is a separate issue. Perhaps time and resources would be better spent elsewhere. However, if Yale were to be renamed, not much would be lost. While Yale may lose some social cache in the short term, the school would retain its acclaim as one of the best on the planet. In the process, Yale would become a more welcoming environment for students, faculty and visitors alike.

Yale’s name change could produce significant benefits. Among other things, it would set an important precedent regarding meritocracy. Great honors, such as having an entire university named after you, should be reserved for those with a lengthy track record demonstrating exemplary character. Elihu Yale does not fit the bill.

Yale has even been renamed before. For the first 17 years of its existence, it was known as the “Collegiate School.” The name change did not take place until Elihu Yale was a senior citizen.

It is also worth noting that Yale is not a stand-alone case. Brown University was also named after a slave trader: Nicholas Brown Sr. And even for a slave trader, Nicholas Brown Sr. was known to be particularly brutal. On a voyage aboard his ship Sally, at least 109 out of 196 abducted slaves perished.

Sites within universities, not just the schools themselves, are not immune to controversy either. Take the University of Maine’s Little Hall, which houses its psychology, modern languages and Franco-American studies departments. Little Hall was named after Clarence C. Little, the school’s president from 1922 to 1925.

Clarence C. Little was also the president of the American Eugenics Society. Perhaps most disturbingly, he held on to his eugenicist beliefs well after the Nazi regime had exposed the horrors of eugenics to the world. Little was also a prominent denier of the harmful effects of smoking. In his own words, “There is no demonstrated causal relationship between smoking and any disease.” Claims such as this made him one of the tobacco industry’s most beloved allies during the 1950s and ‘60s.

The University of Maine is currently looking into renaming Little Hall and has assembled a task force to explore future options. Should the administration choose to do so, they would be joining a long list of schools that have changed problematic names of campus sites.

For the same reasons as the University of Maine, the University of Michigan removed Little’s name from a science building in 2018. The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill removed Silent Sam, a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier, from its school grounds two years ago. Just last month, the Western Carolina University Board of Trustees unanimously approved a resolution to rename Hoey Auditorium. Its namesake, Clyde Hoey, was a segregationist governor of North Carolina who opposed statehood for Hawaii on the grounds that it had “only a small percentage of white people.” Two weeks earlier, Clemson’s board of trustees all voted in favor of removing John C. Calhoun’s name from the university’s honors college. Calhoun is most remembered for his belief that slavery was a “positive good” that ought to be defended through the invocation of states’ rights. He also had between 70 and 80 slaves of his own.

University administrations can easily change the names of buildings and remove statues to create a more inclusive and welcoming campus. And while administrators might have the final say, none of this would happen without the work of committed campus and community activists. It will be interesting to see how both activists and administrators continue with this push going forward.