In all my time spent reading for my English classes, I never thought Shakespeare would be one of my favorite authors to study. Though, to be honest, I can’t help but feel elitist for saying that. It’s not that the modern stories are below me or anything. I just know what I like, I suppose.

When I hear about my friend’s encounters with his work, there’s often a mix of results. Some read the scripts in the same way one might read a novel; others are actors who’ve been previously cast for specific characters.

However, the way someone reads a text can drastically alter the way that particular text is understood. With that being said, I’d like to give a few pointers to anyone looking for advice on how to comprehend and analyze Shakespeare’s plays.

1. Just Read the Text

Look, we’ve all been there: a late night reading SparkNotes on Hamlet’s unsolicited musings. I can totally understand why a busy student would rather read a summary written in the modern form of English than a bunch of weirdos saying words such as “prithee,” “hark” and “alack.”

However, if you really want to do well in a required Shakespeare class, you need to read the original play. If you miss something, or if you feel lost in the complicated narrative webs of the plays, a summary can help you connect the dots.

Yeah, I know — this is how SparkNotes is meant to be used, right? Well, I’m just here to give you a sober reminder of that fact.

2. Audio and Visual Aids

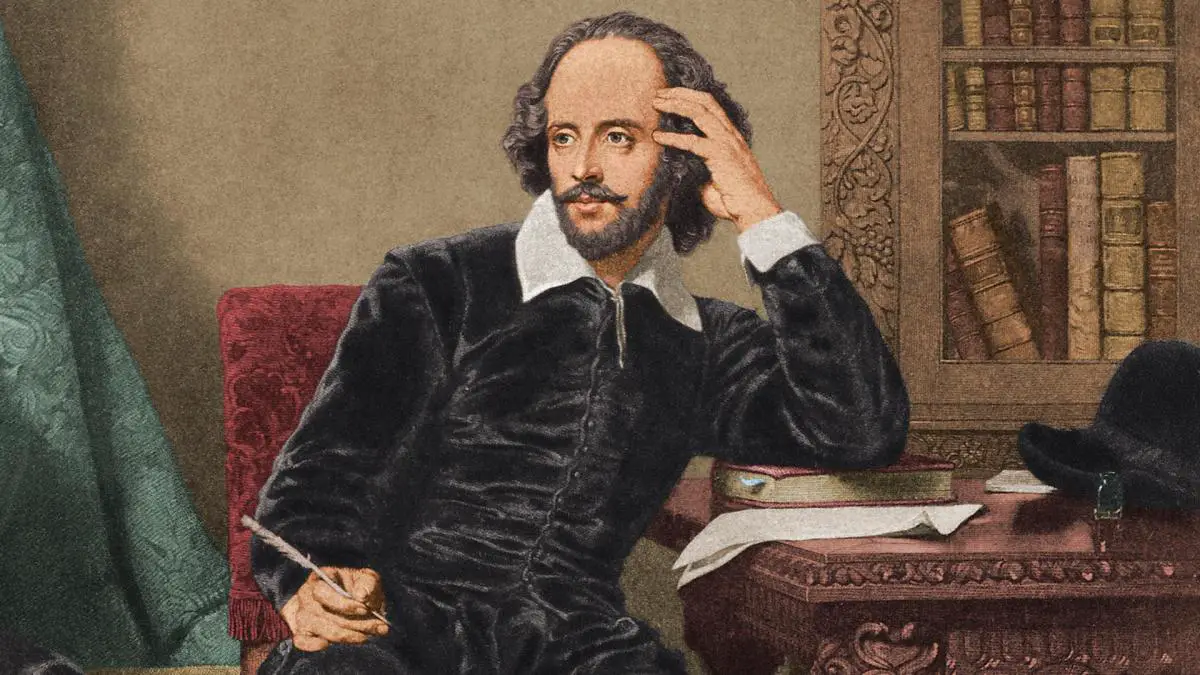

While I’m sure Old Billy dreamed of a future where students read his scripts alone in their rooms, it’s important to remember that his texts are plays. Ultimately, you can’t ignore the performative and theatrical aspects of the stories.

For every play a professor assigned to me, I read the script along with a performance I could find online. Since all of Shakespeare’s work belongs to the public domain, the internet offers many free options for the reader to make the plays a multimedia experience.

When you read along with a recorded performance of a Shakespeare play, you’re able to comprehend the plot not only through the text but also through the intonation and emotion behind the performances. The way an actor says a certain line or word can give the reader hints toward the meaning of any given statement.

LibriVox is a resource I used to find the performances I needed. Luckily, everything they provide is under public domain and, therefore, free of charge. You can use their recordings for anything you’d like.

You could sample them for making music, or you could use the audio for a video presentation. If you’re aspirations lead you to public servitude, you can always use the performances to spice up your political rallies. Honestly, the opportunities are endless.

Just imagine, you, a prospective politician, walking out to a speech made by one of the many shining examples that Shakespeare presents as a worthy leader. I can’t think of any examples right now, but let me assure you that there are dozens, if not hundreds, to choose from.

3. Read “Troilus and Criseyde” by Geoffrey Chaucer

Ok, that last piece of advice kind of strayed away from the texts I’m considering in this article, especially that political rally suggestion. If you really want to take this stuff seriously, then you should consider some supplementary texts.

I know the idea of adding additional readings to your college-level workload sounds like a chore. Trust me, it is. However, Chaucer’s “little book” (“Troilus and Criseyde,” Book 5 Line 256) can help you understand important character dynamics that show up time and time again in Shakespeare’s plays.

The dynamic takes the form of a unique love triangle. In “Troilus and Criseyde,” the two young Trojans find themselves in a romantic arrangement largely facilitated by Pandarus, their mutual, aristocratic friend.

While the motives of Pandarus are unclear, the Trojan war had been going on for about eight years at the time of the story, so I suppose he just felt fed up with the war and wanted to see something different. Troilus, victim to Cupid’s arrow at the beginning of the poem, adheres to Pandarus’ plan. Criseyde, on the other hand, would really rather just read her books and hang out with her friends.

This kind of dynamic shows itself in many of Shakespeare’s works. Hamlet, Ophelia and Polonius all come to mind. You could even find it among Romeo, Juliet and Friar Laurence, although that’s kind of stretching it.

While neither of the trios are entirely derivative of Chaucer’s characters, the relationships within the respective groups show parallels between themselves and what I can assume is their source of inspiration.

4. Don’t Be Afraid to Laugh

The plays, much like many older stories, often put a moralistic skew on their narratives. Shakespeare constantly gives the audience cautionary tales on their desires.

For instance, “Macbeth” warns the audience of the dangerous path toward sovereignty, while “Antony and Cleopatra” offers a lesson on keeping one’s priorities straight. These are by no means the only lessons that the tales tell; however, they are two very important ones.

Even with all the lessons and morals to learn, Shakespeare never lets too many pages go by without making some kind of joke. I mean, the guy wrote more comedies than any other genre, so it’s safe to assume he had a sense of humor.

Even in his darkest plays, such as “Hamlet,” for instance, there are characters who always provide a humorous element to an otherwise bleak story. I particularly love Polonius’ monologue to Claudius when he says, “I will be brief: your noble son is mad. / Mad call I it, for, to define true madness, / What is ’t but to be nothing else but mad? / But let that go” (“Hamlet”, 2.2.94-97).

He tries so hard to impress the king of Denmark but just ends up making a fool of himself for about 15 more lines.

5. Don’t Worry About It

You don’t have to like Shakespeare to be smart or to be a good person. Though, if your professors assign any of his works, the material cannot go unread if you want to fully comprehend the texts. Hopefully, for your next course on Shakespeare, you’ll find some of these tips to be useful.