I Studied Abroad in Beijing and All I Got was this Lousy Expanded Worldview

Babies in China don’t wear diapers, and other fun facts.

By Gabriel Aguilar, University of Texas at San Antonio

Less than two months ago, I responded to an email that asked if I was interested in becoming an English tutor in China through a program called au pairing.

After a few weeks of responding to emails, filling out applications and having Skype interviews every other day, I got the job. The family that chose to house me lived in Beijing, seemed nice and couldn’t speak any English—except of course, for the child I would be tutoring.

Finally, after a montage of drives to Houston for my passport and visa, and studying and taking final exams, my very emotional Hispanic mother and two close friends drove me to the George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston. Prior to Beijing, I’d never left the country—it was the first time I’d ever flown on a plane. I was just a freshman at UTSA who caught a lucky break and got the opportunity to teach English in China, so when I heard the screech of the engines kick to life, I felt every emotion describable. I was afraid, anxious and nervous, but I was also excited and wide-eyed at the idea of living abroad, and my eyes only grew wider as I saw the clouds fold beneath the wings of my Boeing.

I will spare the flight details, outside of saying that it was fifteen odd hours of restless sleep, movies and squeezing out to the bathroom past a man and his wife who cursed at me in Mandarin. The flight had a stop in South Korea in a city whose name I forget, for about four hours. The sample of South Koreans I came into contact with were lively, colorful and bizarre. Bands of Koreans wearing traditional clothing marched throughout the airport while beating drums, and so naturally an audience quickly gathered and embraced them warmly. I, meanwhile, found a café and picked a spot to have lunch. I played language charades with the cashier and was rewarded with a chicken sandwich and a bottle of water.

After my lunch, I rested for a bit as I started to feel jet lag. My internal clock read 1:00am, while Korea told me with a full face of sun that it was closer to ten. A woman in a wheelchair came up to me while I was resting. I took off my headphones and tilted my head. “Are you heading to Vietnam?” she asked in very broken English. She was old and looked tired.

“No, I am heading to Beijing. Peking.” Peking is the traditional name of Beijing for those without a Latin alphabet. She didn’t respond, and went about her way toward another waiting area. Not long after the older lady left me, a stewardess came scrambling up to me. Again in broken English, she asked “Woman in wheelchair, you see?” I didn’t try to speak to her because I was worried it would cause more confusion, so I stood from my seat and gave a hearty point to where I had last seen her roll. She bowed her head at me and called two other stewardesses over, who began jogging in the general direction of my point. Bizarre was the only word I could think of to describe watching three Korean stewardesses chase an old woman in an airport wheelchairing for Vietnam. I gave a quick glance at the Arrival/Departure screen and saw no sign of any flights to Vietnam. Bizarre.

After three hours had passed, I gathered my stuff and headed to the booking area. While in line for the security check, I saw a very tall, old Caucasian man being held by security because his blonde, twenty-something girlfriend was trying to bring seven or eight bottles of Korean liquor in her carry-on. It’s not rude to stare at people in many Asian cultures, and onlookers treated the security fiasco as side-show entertainment while heading toward the booking area. After another half an hour and I was on a Boeing 737—a considerably smaller plane than the Boeing I initially took—for a two-hour ride.

My company for the flight lacked an old Asian couple but made up for it with an overweight mother, complete with a wide variety of in-flight snacks in her purse, and a son who looked to about twelve. The woman ate from take-off to touchdown, teasing fliers with aromas that ranged from sour to sweet, pungent to spicy, and roamed through the cabin and into passengers’ nostrils.

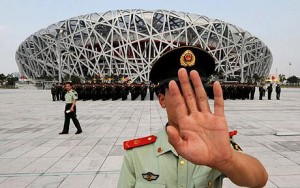

I arrived at the Beijing, or Peking, airport in the blink of an eye. The atmosphere was the polar opposite of what I experienced in Korea. It was as bureaucratic as bureaucratic can get. There was a blatant disconnect between the Customs Officials and the passengers that were coming off the flight. No warm smiles or friendly greetings were exchanged in the airport, and I began to feel tremendously nervous about my stay in China. If I were to survive for three months, I would need some expression from the people that I was going to call my family. Receiving feedback, especially from a people that I know nothing about and will struggle to communicate with, is the most important element to understanding a culture, especially if I want to avoid offending anyone.

I was in a sea of people trying to find family members when I spotted my program counselor, the only woman holding a plastic sign that read “Gabriel” in magic marker,” and began to make my way toward her. She welcomed me to the city and called over my soon-to-be host mother from a section in the storm of people. My program counselor translated all the questions my host mother asked about my flight, but I was in a cloud of sleep deprivation and culture shock and couldn’t focus on what they were saying. Over the past twenty eight hours, I had crossed thirteen time zones with only three hours of sleep; I had never felt closer to the textbook definition of the word “exhausted”.

The communication between my host mother and myself on the car ride home could be generously described as non-existent. She didn’t speak English and my tongue was held to the language very dependently. The apartment complex I would be living in was not far from the airport and took about ten minutes to reach. Her father helped with my luggage as we rode an elevator up five stories from the parking lot to their apartment. They both lead me through the door as I entered a gorgeous living room with white walls and traditional Chinese knots hanging from the center. The grandfather of the family, my host mother’s father, gestured for me to leave my bags by the door as he called for the child that I would spend my summer tutoring. I did as he asked and then walked towards the middle of the living room to inspect the Chinese knot.

This is when I made my first mistake. I had kept my shoes on the entire time as I paced around the living room, which is an offense in Chinese culture. The family that stood in the room with me looked at me as if I’d murdered someone right in front of them. Murmurs in Mandarin skipped about lips and eyes pierced, but naïve as I was, I never picked up the signals until the child came from downstairs. Joey, a skinny kid with eccentric black eyes and an active mouth to suit his character. He pointed toward my feet as his grandmother, who accompanied him from the trip downstairs, whispered in his ear. “You must leave your shoes by the door. They are considered dirty and you cannot wear them in the house.” His English surprised me a bit; the accent was very strong but he wasn’t hesitant to find words from the back of his tongue.

I felt blood rush from my feet to my cheeks. I shook off a bit of jetlag with a healthy apology to the family standing in front of me, then took my shoes off and slipped on a pair of house sandals that the grandfather handed to me. The grandmother whispered in the kid’s ear again. “Are you hungry?”

“No,” I said. “They had dinner served in the flight I was on. I’m more tired than anything, really.” The fact was I slept through the in-flight meal and was a bit hungry, but my longing for a bed and sleep outranked the rumble of my stomach.

Joey translated to the grandmother. She ignored my suggestion and led me toward the dinner table where the family had plates of food ready for my arrival. A bowl of rice sat in front of me with a pair of chopsticks. Embarrassed enough by the shoe ordeal, I did my damndest to immediately learn how to use chopsticks. I failed, and gave a nervous chuckle that my audience returned to me. The kid handed me a spoon and a fork and I pecked at the food that was offered. The rice was as expected, not really a flavor but very filling. The main dish was a very cold, rubbery pig intestine that was cut into small rectangles. The grandfather dipped the rectangle into a brown sauce that was salty and unpleasant. Feeling the cold pig intestine slither down my throat made a shiver run through my entire body, but I did my best to mask my disgust with a smile and a nod to hint that I enjoyed the food.

It was about 9:30 at night when Joey led me to my room. A very quiet bed space, queen-sized bed, a dresser, two night stands, a mirror and a large sliding window with a small balcony. Joey quickly said goodnight and left me alone in the room. I laid down and gathered my thoughts for a moment. It was around 8am back home but I had no way of communicating. My phone didn’t work in China without a SIM card, and I hadn’t asked for a Wifi password. Best to just head to bed, I thought to myself. The pillow was filled with rice and I found it to be extremely uncomfortable. It took a few hours before I finally drifted off.

The first few days of my experience were meshed together in a net of jetlag and culture shock. I restrained myself from going to see the attractions of Beijing, and instead just walked among the people. I got a traffic card from the agency that hired me, and it allowed me to explore the city through the subway and the bus routes.

When I got on the train, the breath was taken out of the car, and I could feel a thousand eyes on the back of my head. It was the closest you can feel to being famous without the fame, just the gawking of a crowd and the embarrassed head-turns when eye contact is accidentally made. After a few weeks of using public transportation to explore the city, the gawking and embarrassed glances eventually died down. I’d never been so happy to just be another person on a train.

I learned that it’s not impolite to stare in China. And unlike other cultures, in Beijing the local people prefer you to attempt to communicate in your native language if your Mandarin is rough. It’s totally fine to talk with your mouth full, and it’s a huge compliment to the chef if you slurp and eat as loudly as you can when having a meal. Babies often don’t wear diapers, and are allowed to just relieve themselves where they are. On several occasions, my host family’s baby soiled my bedroom floor, which I took major shock to, but his family just stood and chuckled while they cleaned the waste with a rag and sponge. Dogs are beyond obedient in the Chinese culture. I can’t recall ever seeing a dog with a leash tied to its collar, but I never saw a dog stray from its owner or get excited when it saw other dogs. I also noticed that foreigners often get ripped off when trying to barter with sales vendors or taxi driver. It’s common for a sales vendor to give fake Chinese currency as change when a transaction has been made, and taxi drivers will often overcharge for a trip in their cab when foreigners decide to hop in.

I visited museums, restaurants, music and dance venues and was mesmerized by the air the people around me expressed. It was as if I witnessed generations of Chinese culture in a single note of music, step of dance, or dish of Peking duck—it was unmistakably unforgettable how the Chinese tended to their respective crafts. Outside of the music, art and culinary outlets, the people in Beijing seemed very uniform. ‘Minding their own business,’ is the best phrase I can attach to the way the everyday Chinese person stood in public, not really smiling at strangers, or holding doors open, or stopping for a beggars. It was very much a Point-A to Point-B type of lifestyle.

But in the home, it is a different story: my host family seemed to celebrate life every day. Of course inevitable bickering occurred, but there was always laughter and dancing in the living room when the family gathered. There was a 7-month old baby in my family, and he was always the highlight of the family’s day. It touched my heart, and sometimes I had to turn away and swallow because it me made me miss my home and family.

Interactions with other people outside my family were rare. I made a friend or two, and one pass romance, but the girls in China aren’t as animated as westerners are in the field of love . Nonetheless, the connections I made in China got me out of trouble— I got locked out of my house, got lost in the woods, cried my eyes out and was rescued at 2:00am by a friend in a taxi—and also gave me people to talk to and share ideas with when all my friends and family were asleep back home.