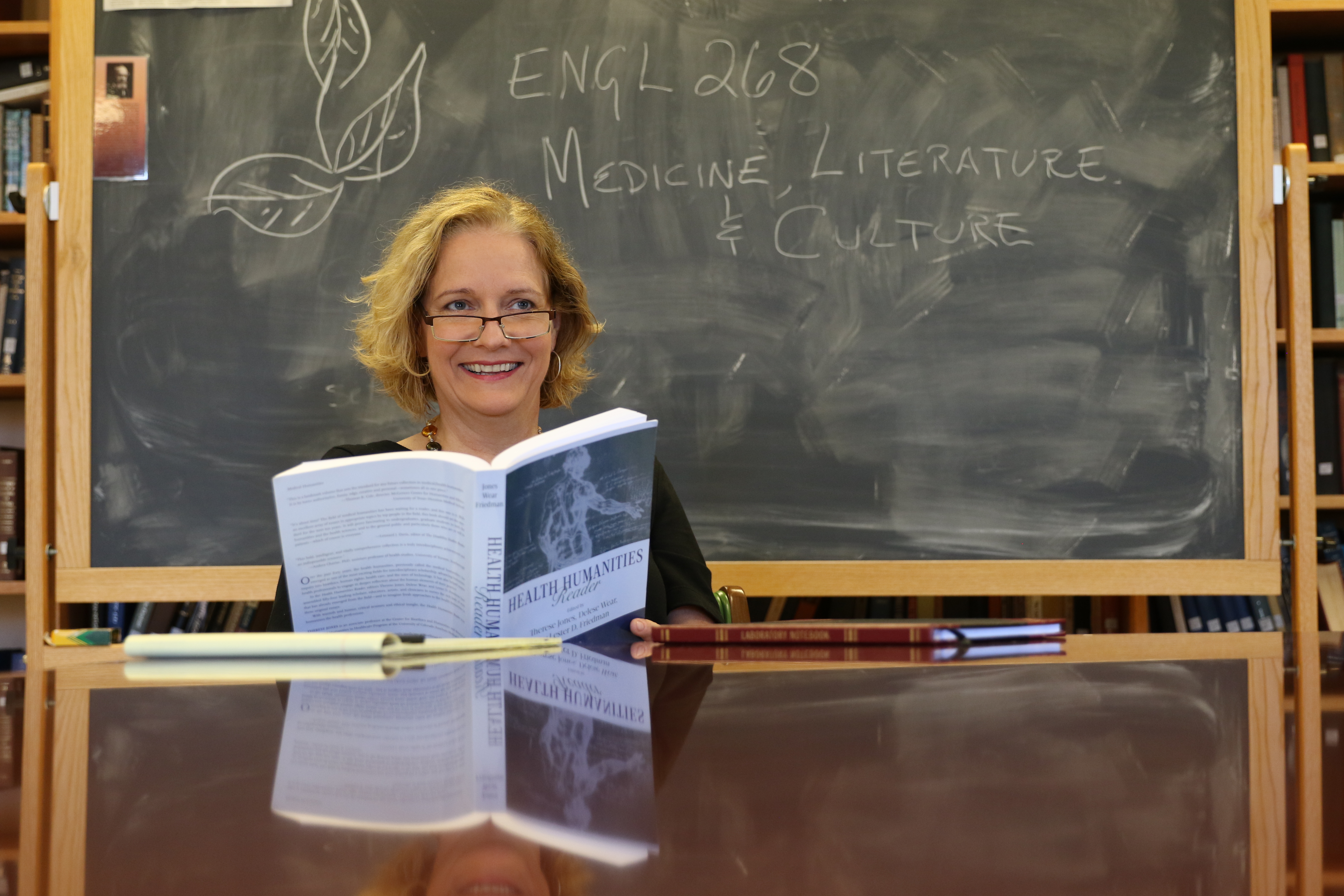

Office Hours with Jane Thraikill

By connecting the past, present and future of medicine to literature, Dr. Thrailkill is paving a new path in public health.

By Josephine Werni, University of Minnesota Twin Cities

Jane Thrailkill is a professor in the Department of English at UNC Chapel Hill, as well as the director for both the M.A. program in the Health Humanities Lab (HHIVE) and Literature, Medicine and Culture.

Her passions lie in studying the complex relationship between medicine and the humanities, which has led her to teach multiple interdisciplinary courses on the topic.

Josephine Werni: How many of these interdisciplinary classes are you teaching currently?

Jane Thraikill: I’m teaching two this semester. Next semester I’ll be teaching one American Literature course, and the other will be a first year seminar in health humanities. UNC Chapel Hill is what is known as a Research One university. Because of this, faculty members never teach more than two classes a semester.

JW: How are the classes typically structured?

JT: The courses are different and they serve different purposes. This one I’m teaching now is called Literature, Medicine and Culture, or English 268. You could call it an introductory course to the study of health humanities. It’s really teaching students a lot about the theory, philosophy, iconic texts and ways of thinking that fall under the umbrella of health humanities or medical humanities.

We read novels and poems, as well as articles about the history of medicine. We hear from anthropologists who explain how culture affects peoples’ attitudes toward life and death, toward what counts as healing, what counts as restorative, the relationship between the spirit and the body, and so on. All of that is what goes on in English 268. I also teach a course called English 695, which is quite different.

JW: How so?

JT: Well, 268 is an 80-person lecture with discussion sections, and it’s made up of undergrads from all different majors. English 695 is a small, intensive research methods course. Students from all levels enroll. In this class, we have them conduct original research in teams and for their final project.

JW: What sorts of research topics have been explored?

JT: Last year, one of the research projects we did was called Writing Diabetes. Our concept begins with the fact that we know how to teach reading, writing and composition. Composition is all about taking the chaos and the endless possibilities of a topic and organizing it into a cogent form—into a narrative that makes sense.

With a diagnosis such as type two diabetes, there tends to be a bit of a life profile, in the sense that sufferers live more complicated lives. Our goal was to find out if individuals who deal with chronic illness would benefit from writing about their experiences, as well as from the discipline that comes with showing up each week and revising. We could check on things such as their circuit level, blood and their sense of coherence and wellbeing. We’re still crunching the data on that.

JW: There’s also an entire M.A. program at UNC dedicated to medical humanities as well, correct?

JT: Indeed, so far it’s really kind of a boutique program. For instance, Colombia University and Vanderbilt University have larger, more traditionally departmental programs in health humanities.

JW: What would this degree qualify students to do?

JT: For some, it helps to confirm that they want to go to medical school. It also provides a way to really get a broad, humanistic, interdisciplinary foundation before going straight into vocational school—whether they’re going to be an occupational therapist, a physician assistant, a nurse, a clinician or simply go full blown public health.

JW: Are there any plans to change or extend the program in the future?

JT: We’re really evaluating that right now, actually. We’re wondering if it might be good to develop a condensed program that can be done in one year so that medical students could do it during their third and fourth year in med school.

We’re thinking maybe we should adapt our program to be less of a full-blown two years Master’s degree, and more of something for people in the health field to take at a certain moment in the course of their medical training.

To learn more about Thraikill’s work, click here.