Working at a college writing center has taught me many, many things about writing, but the most eye-opening thing that I learned was the seven seas that lie between high school English classes and college ones.

The majority of students that come into the writing center are freshman in English 101 and 102, the entry-level English courses that pretty much every student is required to take, unless they are entering the university with college credit.

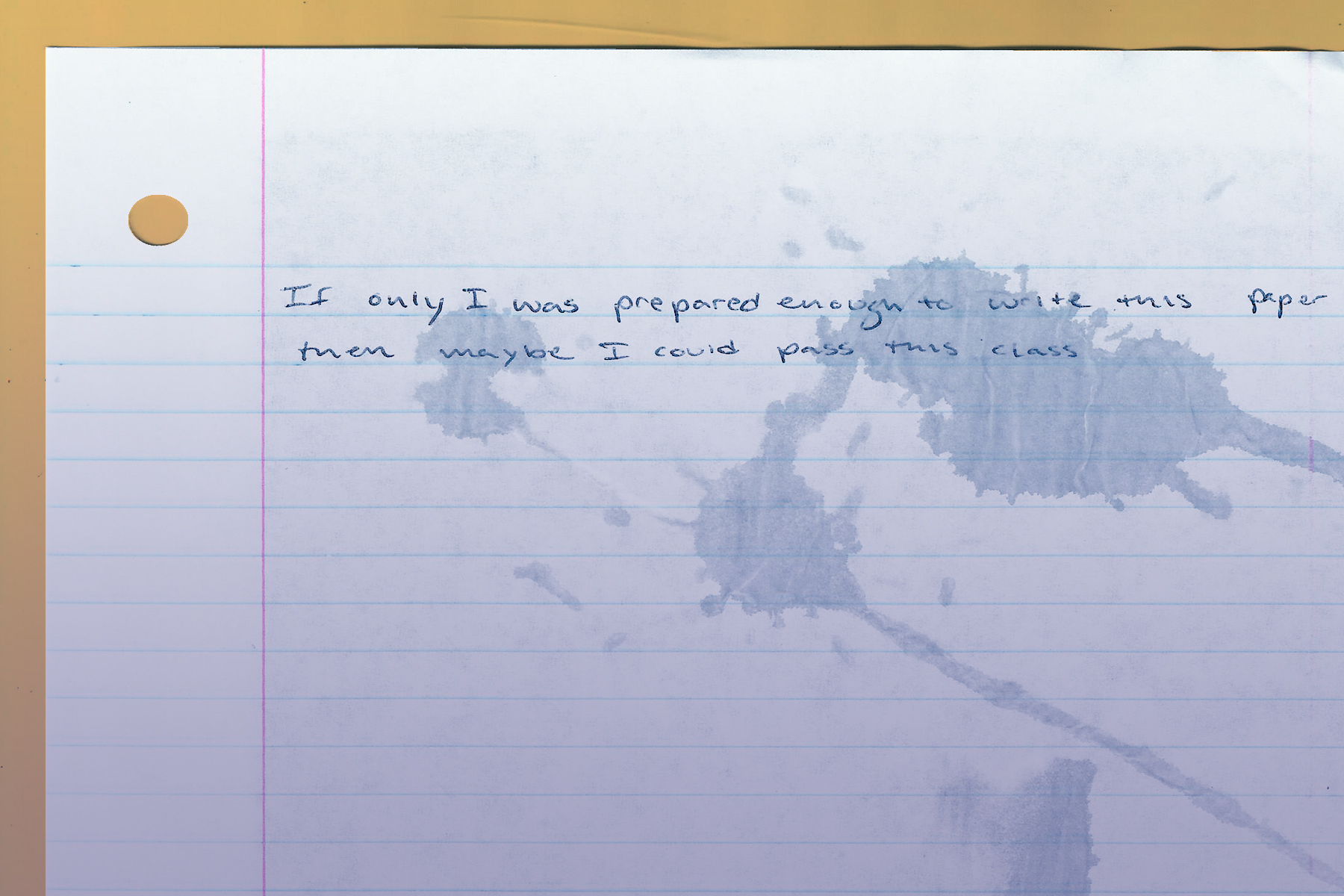

While their talents vary immensely — as some are just have more natural skill in this area than others –– there is one common denominator between all of them: high school failed to prepare them to successfully think or write at a college level.

The first lesson that needs to be learned during this educational transition is:

1. Don’t Expect Your Thesis to Be Given to You

The point I often have to get across to writers coming in for a tutoring session is that the thesis is the most crucial aspect of a paper; it is the heart of the argument and everything else should strengthen and revolve around it. The problem is, this usually stumps their entire writing process, because they have not been taught how to write their own thesis — that is, how to invent their own argument.

Most high school English teachers will give your thesis, telling you that X is the main theme of the book, or that X means Y, and tell you to write about that exact argument. Not only is every student writing the same essay, but your teacher is basically asking you to regurgitate the information they have given to you, so how original and creative can you really be? This process inhibits students’ intellectual gears from turning and formulating their own thoughts, opinions and claims from the content they interact with.

As a result, when they come to college and the only prompt given is something asking to combine the work they’ve read, discussion in class and their own thoughts to write a paper on their own interpretations of a topic, students are stumped. So, if you are a college student and you find yourself making mediocre grades as the result of weak essays, it’s likely because you are still expecting a thesis to be fed to you.

Instead of waiting around for a magic answer, try to:

2. Ask Yourself Questions

The creative process I suggest for my students is to annotate and make notes as they go through a reading. It is so much extra work to read a piece along with the class, and then essentially have to read the entire thing over once your prompt is given to you and you don’t know where to begin.

Instead, as you’re reading, keep in mind that you will eventually need to write something about these words your eyes are racing through. Underline sentences or passages in the reading that seem important or curious to you and make note of them.

Ask yourself questions like, “Why is the writer saying this? Why this way? Why did this particular character do this particular thing? How does it impact the theme of the writing? How can I connect this to my own experiences in the world I am living in today?” If you’re especially frustrated, you might even ask yourself, “Can I just find a genie and wish, ‘buy college essay,’ and solve all my problems?”

Always remember that most writers write out of a sense of lack; there is a problem, a question that they are exploring, and it is most likely because the meaning of their book extends far beyond the confinements of the pages between your hands.

For example, one of the most brilliant professors I’ve ever encountered encouraged my class to ask these types of questions when writing an analytical essay on a poem. He did this by using a poem he thought was so popularized that there was one interpretation that has become absolute: Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.”

However, he didn’t sell us his own interpretation and ask us to analyze it that way, but rather, asked us where we heard it most, and what we all thought it meant. In doing this, he forced us to see that we all had the same interpretation of the poem in mind that was something along the lines of a piece about two roads, one of adversity, and the other the “easy” path.

Where we heard this poem most often were places like high school graduations and award speeches because most tend to interpret it as a poem that applauds overcoming adversity and the long-term pay off. And, maybe, that it what it means! But that’s not a concrete fact.

My professor asked us to reread the poem closely and analyze it by underlining the words or lines that helped us interpret what Frost’s intentions. He urged us to ask ourselves questions, like “Why does Frost use this word? Is it in a positive way, or a negative way?” and “What does this really mean? What is your experience with this feeling in your own life?”

What my professor was doing was purely Socratic; the goal was not to tell us anything, but rather to force us to break this poem down into its most raw form, set aside our previous biases about its meaning and analyze it ourselves. Some of the class agreed that Frost was writing about two different roads in life –– the easy and the difficult –– and favoring the path of adversity that would lead to more success in the end.

However, a new interpretation also arose among my peers that suggested that Frost was actually being a bit negative, that what he was saying is there are often two paths you can take in life, equally as “fair” and beautiful, but we as humans can only pick one.

Since our lives are too short to be able to see where we would end up if we took both, we are forced to arbitrarily choose one and, no matter which we choose, remain forever resentful at the fact that we don’t know if our life would have been better had we chosen differently. The latter is the interpretation I was sold on, and it has changed my perspective on the poem and my life ever since.

I use this always use this model when assisting students develop a thesis, trying to push their boundaries the way my professor pushed my class. I encourage them to ask themselves questions about what they’re reading, to prove to me, themselves and their audience that their analysis is defendable.

In doing this, I can see the light bulb that flicks on when they either change their mind or realize that they can break down their stream of consciousness into a beautiful, understandable explanation. This changes the way young writers can analyze work and reflect their thoughts onto their papers, and that “has made all the difference.”

The final piece to the collegiate writing puzzle is remember to:

3. Be Confident in Yourself

Oftentimes when I am tutoring a student, I’ll see some inconsistencies in their paper when they make a claim and don’t flesh it out any further or fail to explain it well to the audience. Having been told repeatedly by high school teachers not to insert their own opinions into their papers and stick solely to the book, students don’t know how to combine what’s on paper with what’s in their head; they have no confidence in their own interpretations.

When this happens, students’ language tends to be vague and formulaic, and, consequently, their voice is lost, along with the credibility of their claim. So, I get Socratic and start asking them questions and, oftentimes, a stunning explanation will just pour from their mouths as they nervously try to defend their paper to me, and I can’t help but nod my head vigorously and point to their paper, saying, “Say that! Say exactly that!”

At my reaction, the student usually lights up and begins to just write what is in their head. Nine times out of 10, it takes their paper from a bland, high school-level paper to an extraordinarily analytical one that is compelling simply because they are making an original, clever argument. It’s not that I have given them any words to say, but the confidence to write their own down on paper. The difference this makes in these essays is profound, so as a student you must be confident in your abilities to write about your own interpretations you formulate after reading a text.

What’s been made very apparent to me, is that most don’t believe these skills are crucial no matter what your major is. The fact is, to be a great college-level writer you have to throw away the majority of what high school teachers taught you, and let your professors push you to take the tools and information they give you, and run with them. Be confident, let your voice shine and never stop asking questions. These simple switches in mindset will transform you as a writer, a student and a life-long critical thinker.