To some, there is something wonderful and exciting about stories that center around the magic of stories; to others, the best thing to do is tell your own story, rather than pay tribute to others. Whatever your inclination, “Three Thousand Years of Longing” knows exactly where it stands on the matter. The film is a bold and often charming meditation on the power of stories and the role they play in shaping the human psyche. It’s admirable in its striving for originality, despite the fact that it’s based not only on centuries-old tales but also adapted from a short story. And from a director whose filmography is largely made of sequels, a thematic departure is always welcome: the more outrageously different, the more intriguing.

Unfortunately, for a movie about storytelling, there are too many confusing choices on the writers’ part to keep the praise going. The first and second halves of the film are so different that you could almost split “Three Thousand Years of Longing” into two separate films featuring the same characters. The first hour or so is an eye-popping study in vitality and desire, an odyssey through the last three thousand years in the long life of a Djinn, or genie (Idris Elba).

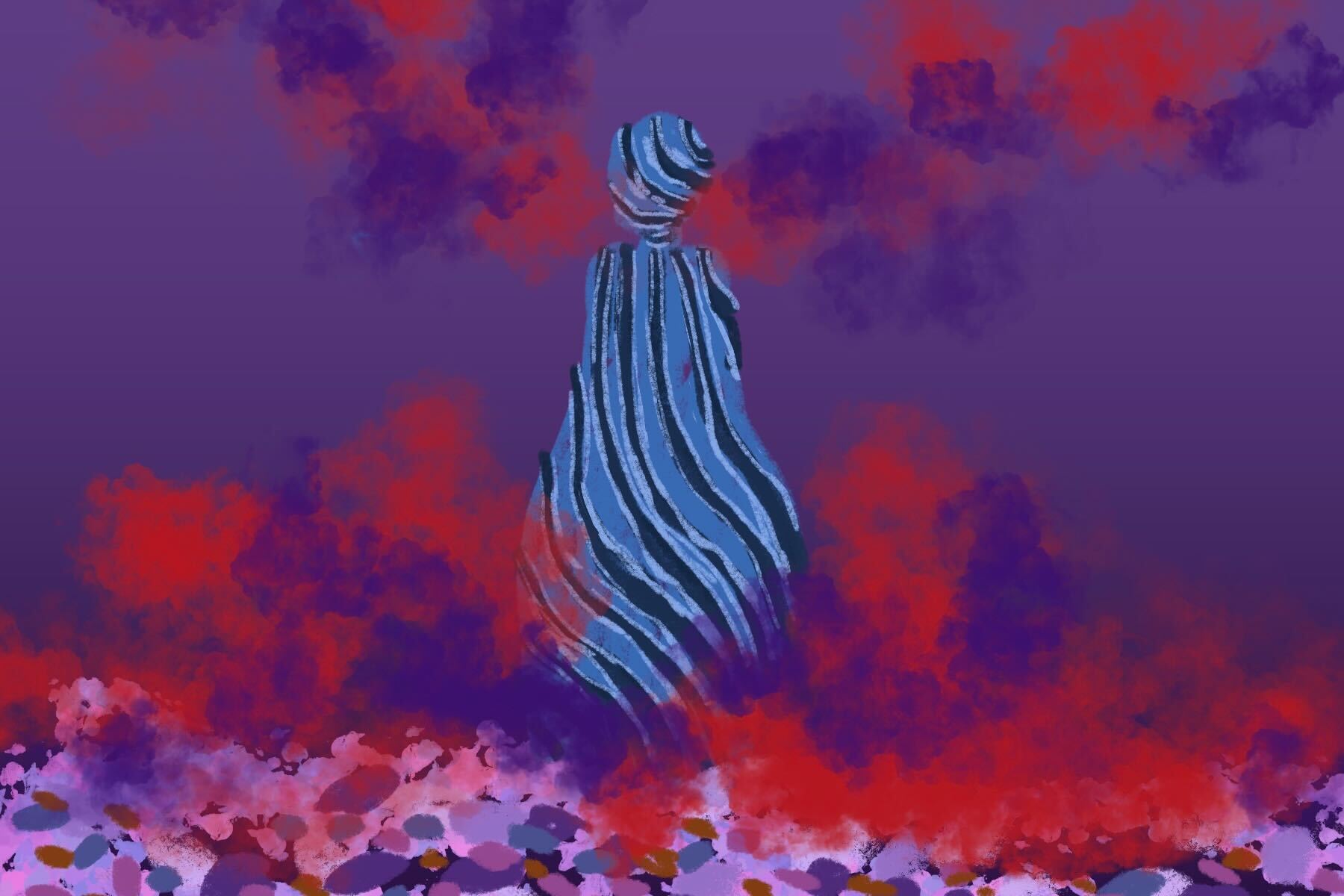

Through the Djinn’s stories, we fall headfirst into worlds where passion, sexuality and conquest reign supreme, and we indulge in the escapism they provide. Every character — particularly the three women who stole the Djinn’s heart — pulses with energy and desires that are crucial to the human condition, whether they be for undying love or infinite knowledge. Though they are, to our modern eyes, nothing more than fairy tales, George Miller and his team bring them to life beautifully and ardently.

Even during these elaborate sequences, though, you’re aware that the film must amount to more than a genie telling stories to a woman in a hotel room. Where will it go next? Right when you start to ponder this, the film makes a sharp turn and takes a whole other direction. This is where the disjointed second half comes into the picture.

I suppose now would be a good time to loop in Alithea (Tilda Swinton), the protagonist of “Three Thousand Years of Longing” and the woman who releases the Djinn from his bottle. The film begins with Alithea, a scholar of stories by profession, traveling to Istanbul for a conference and, after experiencing some strange visions, meeting the Djinn in her hotel room. It is here that the Djinn does what every genie must and offers Alithea three wishes of her choice.

But she has done her homework on these situations and knows that nearly every story about wishes is a cautionary tale. The Djinn reminds her that every human has at least one deeply hidden desire, but Alithea assures him she has none. The two are at a bit of a stalemate until the Djinn recalls his history to her, how he has been doomed by humans and particularly by his longing for them.

The film’s aforementioned sharp turn arrives at the end of the Djinn’s story when Alithea decides her deepest desire must be for the Djinn to love her. When I saw this, my first reaction was: “What?” She denies that she has any latent desires at the beginning of the film, including a desire for the love of another being. Then, at the end of the Djinn’s tales, she suddenly wants to love the Djinn for the rest of her life. There is no build-up to this decision — no hints that she might not have been telling the truth when she spoke of her desires — and no indication that she had any romantic feelings for the Djinn up until that moment. It simply comes out of nowhere.

I had expected there to be some kind of romance based on the genres given (it’s classified as a fantasy romance by Google), but this choice was so abrupt and unfounded that it completely interrupted the flow of the narrative, turning it into something else entirely. Writing bold choices for characters to make is not always a bad thing — but it only works if you plant a seed for that choice in an earlier part of the story. Alithea, of all people, would understand this, which only makes the decision on the writers’ part more frustrating.

In romances, sometimes you can forgive poor writing if the couple has good chemistry. A previous film of Elba’s, “The Mountain Between Us,” is a testament to that. But here, Swinton and Elba, though both incredible actors, don’t exactly send sparks flying together. If anything, their characters seem more intrigued by each others’ minds than attracted to one another in any romantic way. Yet, all of a sudden, after Alithea’s declaration, there is an erotic scene between them that seems to be the culmination of their long conversation. To make a truly intimate sex scene in any film work, you need to have some kind of build-up. “Three Thousand Years of Longing” had absolutely none.

The minute the film turned this relationship into a romance, the little amount of intrigue that buzzed between the characters lost its charm. This is largely due to the fact that the Djinn shows no romantic interest in Alithea but agrees to her request because, well, he has to. She asks him to love her — knowing he isn’t free. Shouldn’t a scholar of stories know that that’s not at all how love works? That your own desire for love should never impinge on another person’s autonomy?

As a historical fantasy, “Three Thousand Years of Longing” soars to new heights and will surely be a delight for lovers of that particular niche. But ultimately, the film’s message is grounded in the unbalanced relationship between Alithea and the Djinn, a dynamic that lacks the palpable energy needed for every great romance. And once the Djinn’s stories are over and the supposed romance takes the stage, the magic of the Djinn’s tales is lost, replaced by a story that, for a film dedicated to storytelling, is ironically very disappointing. If you enjoy films for their cinematography, you might want to try “Three Thousand Years of Longing” just to experience its many visual triumphs. If you go to the movies to fall into a great story, though, you’ll probably want to stay home.