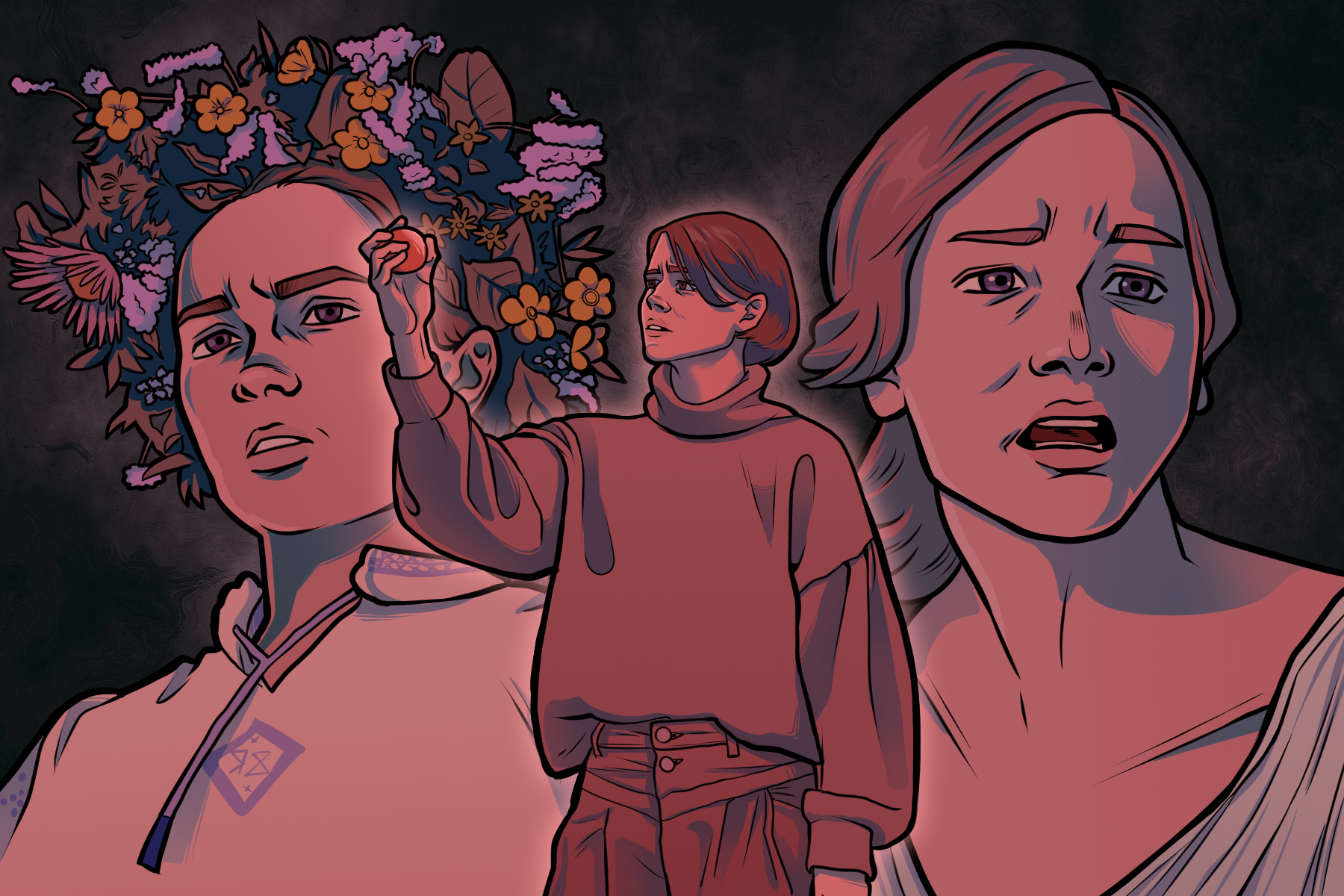

Oddly enough, the common denominator between every horror movie isn’t blood, or jump scares, or killers: It’s trauma. Every protagonist that survives a horror film is left with unspeakable trauma, and that, conveniently, is almost always where the movie ends. What’s more, the horror genre has long featured women as both the protagonists and the victims; in slashers, these women are often called “final girls.” Think of the most iconic horror movies you know, the ones you grew up watching while hiding behind a blanket: “Halloween,” “Scream,” “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” “Candyman.” All of them feature young, white women as the leads, and monstrous men as the killers. There are a few outliers, like “The Shining” and the “Evil Dead” trilogy, but there’s no denying the crystal-clear pattern within horror and that nearly all of the genre’s most popular films follow it — which brings me to the subject of “elevated” horror and specifically its most recent entry, Alex Garland’s “Men” (2022).

On a basic level, “elevated” horror is a relatively new term referring to the horror films that focus more on emotionally devastating themes rather than on gore or jump scares, though they often include those elements as well. Every movie buff knows some of the most popular directors at the helm of this subgenre: Ari Aster (“Hereditary,” “Midsommar”), Jordan Peele (“Get Out,” “Us”) and Robert Eggers (“The Witch,” “The Lighthouse”). Horror aficionados and film critics have debated over whether the term is irrelevant or elitist, or whether it should even exist.

Some have pointed out that what we’re calling “elevated” is really just plain old psychological horror, a subset of the genre that’s been around since the beginning. Whatever the disagreements, it’s clear that there’s been a new wave of arthouse-leaning horror films that weave more allegories and social issues into the narrative than conventional horror movies tend to do. And because these new films are fundamentally psychological horror stories, they also involve trauma — especially women’s trauma — more explicitly. This theme plays a particularly big role in three films of this kind: Darren Aronofsky’s “mother!” (2017), Ari Aster’s “Midsommar” (2019) and “Men.”

“Men” is Garland’s third feature and his most controversial film to date, as well as the most divisive among the three movies mentioned above. Starring Jessie Buckley and Rory Kinnear, the film follows a woman named Harper, who, reeling after a personal tragedy, retreats to the English countryside to try to heal from her past. But soon after she arrives, a man from the nearby woods begins to stalk her. Things only become more terrifying as the plot unfolds, leading to a shocking finale that will undoubtedly leave your head spinning. From the reviews I’ve read, written by both critics and general audience members, this last act is what makes or breaks the movie for most viewers, in addition to Garland’s focus on misogyny, patriarchy and, as you may be able to glean from the title, the social pressures that men force upon women.

Many viewers have groaned at the fact that yet another male director has made a movie about how “men suck” without saying much else, using subjects like domestic abuse to comment on patriarchy; others, however, have praised the film’s originality and boldness both visually and thematically. I enjoyed the film, but I also had to reflect on how Garland wrote his main character and her struggles. The more I thought about it, the less sure I was about my feelings about the movie as a whole. After seeing the film, I thought back to “mother!” and “Midsommar” and realized how similar all three films really are, in different ways.

Both “mother!” and “Men” comment explicitly on patriarchy and employ tired symbolism for these ends (the house as the environment, the apple as the forbidden fruit). In contrast, “Midsommar” doesn’t focus on misogyny the way the other two films do, but the theme nevertheless plays a critical role in the plot. Moreover, Dani’s (the protagonist of “Midsommar”) and Harper’s narrative arcs share a great deal in common, with both characters trying to recover from a horrible tragedy at the beginning of the film, going on a retreat of some kind to heal, and ultimately ending up with even more trauma to process.

What should we make of these similarities? Furthermore, what does it tell us that two male-directed horror films that deal explicitly with patriarchy and gendered trauma face a lot of resistance, while another male-directed horror movie that comments on the subject more subtly receives critical acclaim?

Reflecting on these questions inevitably leads us to an issue that’s been festering in the culture for a while now: separating the art from the artist. In this case, when someone makes a work of art that comments on gender politics, you cannot take the artist’s gender out of the equation. It’s an inherent element of how the work was made and why it turned out the way it did. This isn’t to say a man shouldn’t make a film about misogyny. But the critiques of his film may at least in part be informed by the fact that he is making a movie about an oppressive system he benefits from.

Thinking along these lines, I then asked myself: How would a horror film directed by a woman, focusing on women’s trauma, function differently? Some prominent horror films written and directed by women include “The Babadook,” “Revenge,” “American Mary,” “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night” and “The Nightingale.” Interestingly enough, half of these films — “Revenge,” “The Nightingale” and “American Mary” — are rape and revenge movies, a genre long considered part of the ‘70s exploitation film movement but in recent years has shifted into the categories of horror and thriller. And although “Revenge” and “The Nightingale” may not fit traditional horror conventions, the genre is ultimately about terrifying the audience and revealing the darkest parts of our society, which these two films do successfully.

What’s more, the very nature of the revenge film means that women’s trauma is not just backstory or collateral damage by the end of the movie; it’s always, no matter what, front and center. You can’t forget what these characters have gone through, because they have, against their will, been defined by it for the duration of the narrative until they get their revenge. The devastating effects of trauma are never used solely as commentary. They act as the primary emotional drive, always highlighted and never secondary, as it is in some other horror films — including “Men.”

The choices made by leading male and female horror directors reveal a great deal about just how much gender can inform a director’s understanding of the dangers that women face within society and how they incorporate the issue into a narrative. I certainly don’t think it’s a coincidence that the women-directed horror movies with female protagonists are more likely to prioritize the effects of gendered trauma and less likely to use the topic for the purpose of commentary. When social commentary is the primary motivation in making a movie, as it is in the case of films like “mother!” and “Men,” one can’t help but feel that the writer-director has done their main characters a specific kind of disservice, creating them not from a place of empathy but as a sort of puppet or mouthpiece.

But the recent generation of female horror creators knows better than to use their heroines in this way. Sexual abuse, for them, is not an abstract issue but a fact of life, something that every woman has either experienced or fears. Men who make movies about misogyny and patriarchy are always outside of the experience themselves. Herein lies some explanation for the controversy surrounding “Men” and “mother!” — there is something instinctually frustrating about this, even if one can’t justify that frustration. When compared to other horror films created by women, directors like Garland and Aronofsky fall short of depicting the women in their films with the respect and complexity that they deserve, which only adds fuel to the fire.

Unlike some reviewers, I would not call “Men” a terrible movie. Instead, I would say Garland made a good effort, that his eye for visuals and atmosphere is admirable, but that there’s something a little off in his portrayal of a woman suffering non-stop at the hands of the patriarchy. Before turning to films from women like Jennifer Kent (“The Babadook,” “The Nightingale”) and Coralie Fargeat (“Revenge”), I couldn’t quite put my finger on just what went wrong. But after watching their movies, I realized that it simply comes down to how much depth the creator is willing to give their heroine, not as a vehicle for commentary but as an autonomous individual in her own right.

If there’s one thing I’ve taken away from “Men,” it’s that men have a long way to go before they can make art about the violation of women that goes beyond social critique, and embraces the nuances of the individual.