Imagine waking up, bustling through your daily routine and suddenly being told that you need to relocate immediately, or else you and your loved ones will suffer the fatal consequences. Imagine growing up in a world where you are not welcome, where you have no free will and where you cannot reap the harvest from the seeds you have sown. Imagine a life under the sovereignty of a governor who neglects you, violates you, takes advantage of your work ethic and steals all of your natural possessions — a governor who steals even the rain.

Can you visualize this dismal life? It is the reality that many indigenous Americans face.

“Learn English. You live in America.”

“Go back to your own country.”

“This is our land.”

“You don’t belong here.”

Unfortunately, there are many condescending phrases that slander our nation’s ethnic minorities to this day. The exploitation of indigenous people in the Americas dates back to the year 1492 when, you guessed it, the legendary explorer Christopher Columbus set sail off the Spanish coast and “discovered” the New World.

Columbus described the indigenous Americans he encountered, the Taino, as pleasant and handsome people. They willingly traded their goods for those of the Spaniards and were nothing but peaceful. However, Columbus and his men enslaved the Taino people to satisfy their innate greed with native riches. The natives were raped, mutilated and slaughtered, and their homeland was sabotaged by the foreign civilization.

Northern-American history textbooks are great at teaching Columbus’ seemingly heroic persona, but they fail to show how he and the Spaniards ultimately vandalized the native communities. Textbooks use words with positive connotations to describe the European discovery of the new continent; these affirmative words include but are not limited to conquer, explore, discovery and colonization. North-American students have been handed a dangerous schema by an elementary education system that characterizes Columbus as the good guy.

“Even the Rain,” directed by Icíar Bollaín, is a movie that portrays the truth, which is rarely even found in documentaries. It is set in present-day Cochabamba, Bolivia, during a period of local uprising against the privatization of water.

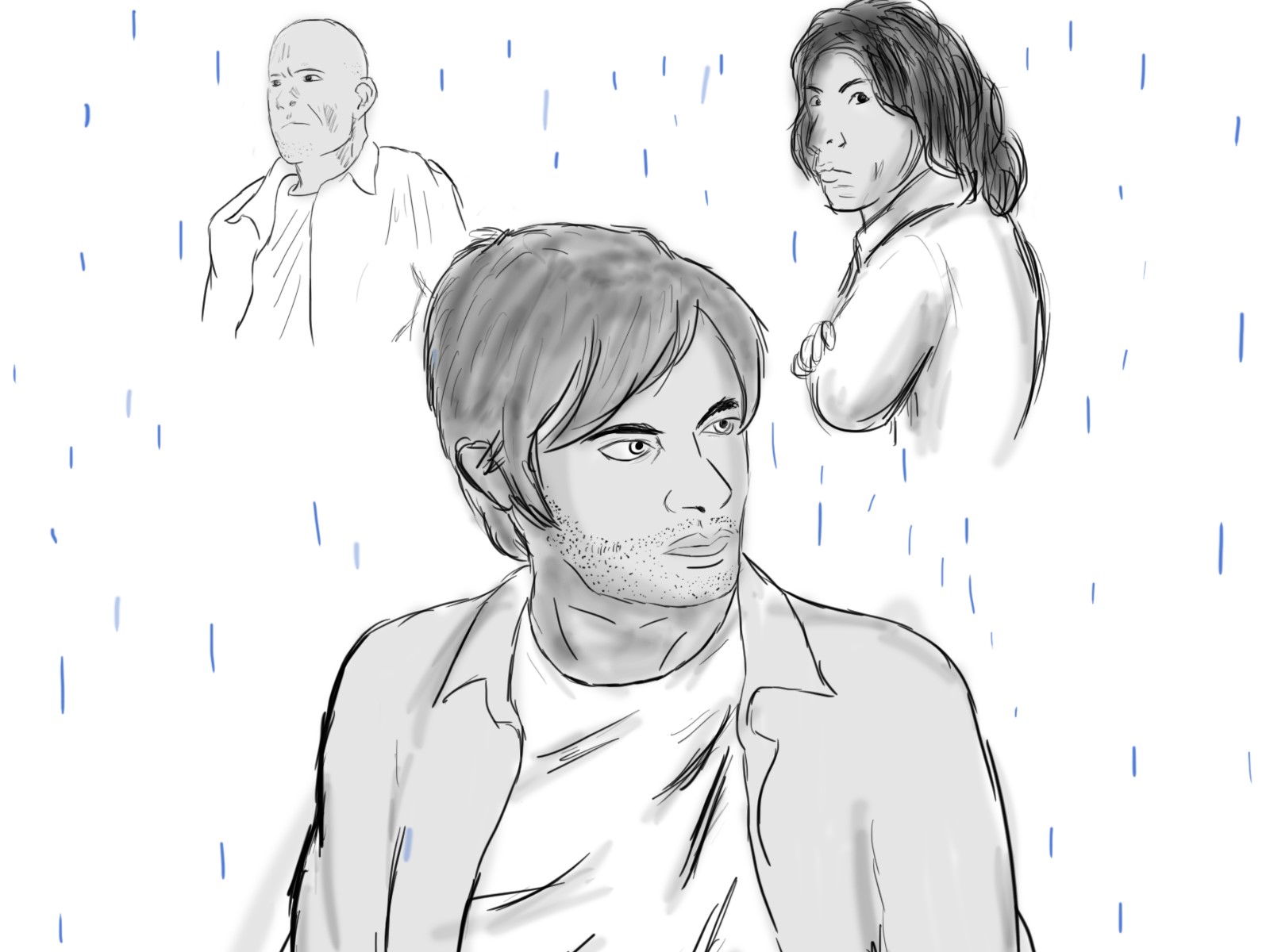

The first scene begins with an acting audition. The director, Sebastián (Gael García Bernal), is passionate about creating a film that tells the truthful horrors of Columbus and the Spanish conquest. Costa (Luis Tosar) is Sebastián’s film producer who also has a deep desire to complete the Columbus exposé, but his motives seem a tad different. Up until the very last scenes of the movie, Costa is in it simply for “la plata”: the money.

Their movie highlights the horrific acts of Western explorers toward the Taino people, and the Spaniards are compared to immoral pirates: they enslaved the natives, they killed for gold and they tortured those who attempted any kind of rebellion against them.

Furthermore, they forcibly converted the natives to Christianity and murdered those who continued to worship their indigenous deities, which is accurately portrayed as hypocritical. Bartolome de las Casas (Carlos Santos) and Antonio de Montesinos (Raúl Arévalo) are two historically accurate Spanish priests who see this corruption in the church and stand up in defense of the native peoples.

Another rebel shown combatting colonial exploitation is Hatuey, played by Daniel (Juan Carlos Aduviri) in Sebastián’s movie, who makes numerous efforts to defend his fellow indigenous people against Columbus and the other Westerners, eventually leading to his martyrdom.

Meanwhile, as Daniel is playing this character, he is simultaneously leading his own revolution against the Bolivian government, which privatized a rural well in the indigenous neighborhood where he and his family live. Multiple scenes in “Even the Rain” depict Daniel’s protests where riots, violence and political corruption fill the capital’s streets.

This present-day Bolivian uprising mirrors the exploitation of indigenous peoples that still occurs in the Americas. Take the Dakota Access Pipeline Protests of 2016, for example; protesters were defending the Native Americans and their main water source, the Mississippi River, against the proposed expansion of the Dakota Access crude oil pipeline. Similarly, Latin American natives and mestizos — those with mixed Spanish and indigenous bloodlines — are often overworked, underpaid and physically ill due to the dangerous conditions of sweatshops from which many North-American corporations source their materials.

“Even the Rain,” accurately conveys both the past and present hardships that indigenous peoples in the Americas endure. Watching this movie means wiping away the false portrayal of the Spanish conquest and replacing it with a revitalized empathy for Latin-American indigenous peoples.

The script was originally written in Spanish and Quechua, an indigenous Andean language; however, the version available on Netflix offers English subtitles for the average English speaker’s viewing convenience.

But do not assume this will be a boring movie because of the history and subtitles. The Spanish script provides a detailed focus on discrimination, like the language discrimination that still holds a tight grip on many English-speaking hearts. You won’t be able to take your eyes off the screen, and you will probably cry.

Most of us are fortunate enough live in a nation where political and ethical exploitation is illegal, but the emotional repercussions of indigenous segregation and neglect are still prevalent. A sincere thank you goes to director Bollaín for educating us, defying the exploitation-is-history status quo and prompting us to seek earnest equality through his work “Even the Rain.”