Standalone novels work as theatrical releases, occasionally translating across mediums effectively enough to eclipse the original text in storytelling prowess and acclaim. Alternatively, extended literary series, with their expansive casts of characters and rich lore to their story world, usually do not. Upon the occasion that the latter is adapted to film, the result is often a bloated mess that attempts to cram too much information into a single two-hour script, a futile attempt to compromise between launching a blockbuster cinematic franchise and safeguarding against a potential financial bust.

Filmmakers would ideally desire to craft an entire multi-episode story based on popular literary series at the necessary methodical pace for world building and character exploration, but Hollywood producers fear the fickle nature of moviegoers and refuse to financially commit to new cinematic properties without the impossible promise of a perpetual lucrative return. Trusting that a new story requiring multiple entries to sufficiently adapt will make enough money to fund those necessary additional films just isn’t realistic when the same cash could be put toward another superhero film, for example, that practically guarantees massive amounts of income.

As such, on the rare occasion that an adaptation is greenlit, executives give writers and directors one film to create a breakout hit, and with that pressure looming over the production, the creative minds behind the project try to fit as much material within a two-hour window as possible to hastily hit the source material’s most memorable moments and generate intrigue within audiences. Of course, without proper character introductions, motivations and story explanations, such an adaptation would be lucky to result in anything but a confused, compromised disaster that fails to capture the magic of the original.

This is a conflict of two drastically different forms of storytelling being forced into the same artistic mold. With one key exception, it’s not possible to properly tell a story with an overarching story that spans multiple novels, each hundreds of pages long, in the time block of your average Hollywood movie. It doesn’t matter how much time could potentially be saved showing a setting or character rather than describing its appearance with text. It doesn’t matter how much faster action scenes can be portrayed visually rather than verbally. It’s very nearly impossible.

The aforementioned anomaly to this truth is the “Harry Potter” series, which in large part successfully capitalized on J.K. Rowling’s explosively popular series of children’s novels while maintaining the literal magic of the source material. However, the Potter films are just that—an anomaly. The series’ structure begins as episodic while vaguely hinting at an overarching story to branch out farther down the plot, thus allowing the filmmakers to tell a satisfying, self-contained story while carefully strategizing for an extended franchise should the series strike economic gold. Of course, considering the books had already spread to the mainstream, the odds of “The Sorcerer’s Stone” tanking were low; excepting complete cinematic ineptitude on the part of the writers, actors and director, it was the closest thing to a safe bet Hollywood could receive from a novel series.

Furthermore, the Potter films remain a lighting-in-a-bottle example because of how much could have gone horribly wrong. The child actors could have grown up to eventually become woefully unsuited for their respective roles, different directors crafting the films could have muddled the pacing and tone and, without knowing the series’ canonical ending before filming the first movie, the foreshadowing could have been mismanaged. Harry Potter was the perfect storm of financial security and luck, ripe for a Hollywood franchise in ways no other literary adaptation since could have possibly lived up to.

“Lord of the Rings” could serve as another example, but considering each of those films are at least three hours before accounting for the vastly superior extended versions, they’re hardly a Hollywood norm. The point is, unless another perfect situation such as “Harry Potter” presents itself, it’s severely unlikely that another feature-length adaptation of a long-running novel series can achieve anything but a catastrophe of cinematic confusion.

This is the precise problem that plagues the Hollywood adaptation of Stephen King’s lauded novel series “The Dark Tower,” which was met with harsh critical reception, following several years in tumultuous development, upon its release on August 4. Ultimately subjected to the unfortunate fate that the book series’ dedicated fandom fearfully anticipated for the exact reason listed above, the film attempted to cram the great majority of seven extensive novels’ worth of material into a single movie. The resulting work disappointed those same fans with its shallow portrayal of the series’ layered fantasy worlds and characters, while baffling newcomers and critics alike with a jumbled, rushed plot that connected a conclusively incomprehensible film.

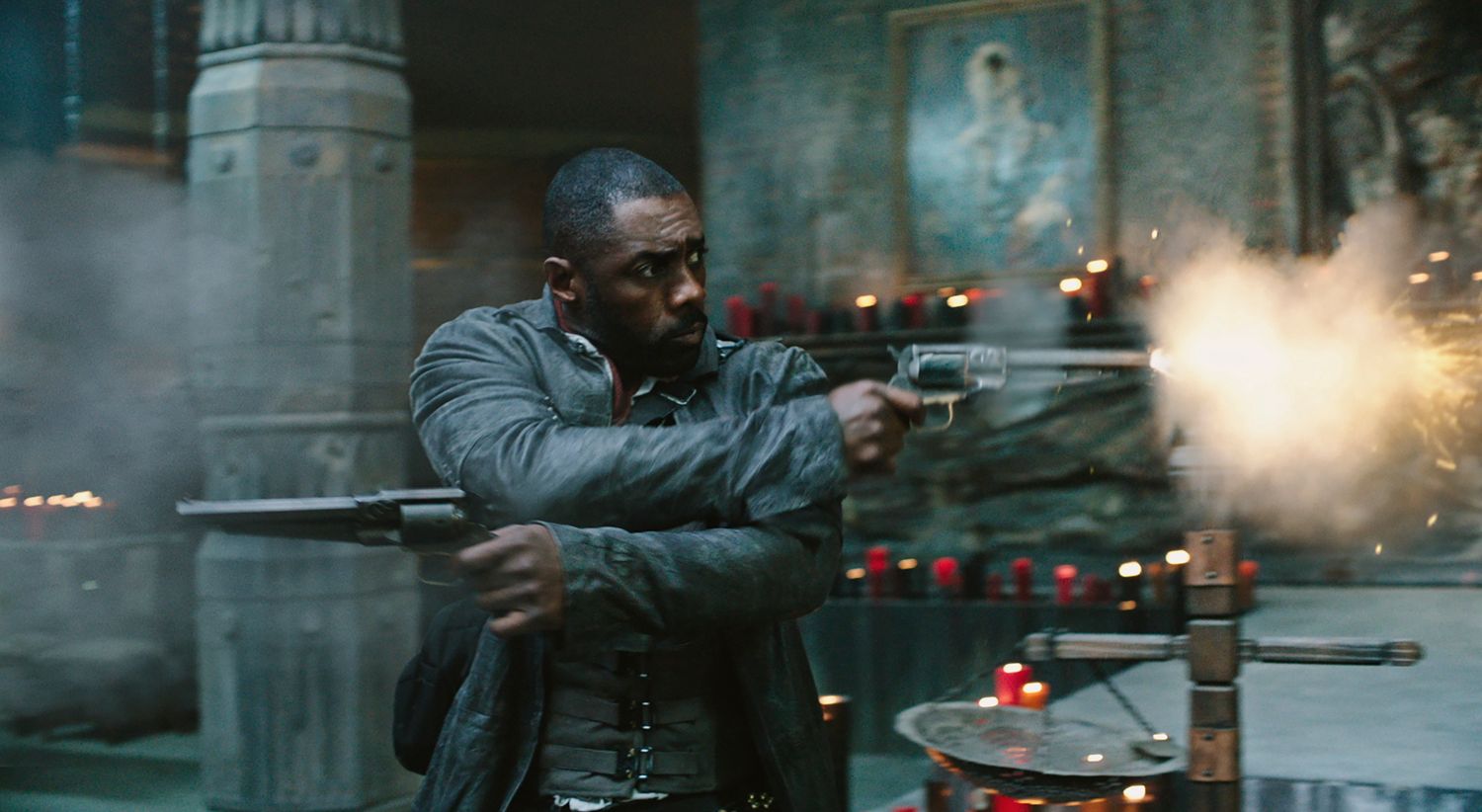

Whereas “The Dark Tower” may have underwhelmed as a feature film, however, it maintains a healthy chance to redeem itself on another medium of visual entertainment—television. Despite the critical failure of the Hollywood adaptation, the series has also been confirmed for a canonical television series more closely resembling the tone and pace of the original books, starting from the first entry, “The Gunslinger,” and starring Idris Elba in the role of titular protagonist Roland Deschain, the one element of the theatrical release that received universal praise.

As “Game of Thrones,” another series once thought to be unadaptable by its dedicated core of readers, has so thoroughly proven, even the most richly detailed fantasy worlds, with intricate overarching characters and plots spanning several entries, can be successfully recreated on the small screen, as the mediums of literature and television entertainment are more naturally suited to each other. The season structure of a television show closely resembles that of a single novel, leaving plenty of time to dedicate over multiple hour-length episodes to properly explore each major player in the story, the world’s history and the breadth of unfolding story events. The increased amount of screen time allotted for writers and directors to flesh out an epic tale and the universe it inhabits allows them to avoid the pitfalls a Hollywood film would typically face when adapting the same material.

Take “A Series of Unfortunate Events,” for instance. The dark, eccentric children’s books penned by Daniel Handler under the pen name Lemony Snicket were exceptionally popular for millennials during their childhoods, but the 2004 Hollywood adaptation starring Jim Carrey as the dastardly, infamous Count Olaf failed to launch a successful film series covering the story in its entirety. While the movie effectively captured the sinister, eerie tone of the source material, it was painfully obvious that the story could not work as a single cohesive film; the decision to simply cover the first three books, all taking place in drastically different locations with their own zany characters, didn’t do the adaptation any favors under the scrutiny three-act structure expectations. Three separate literary stories crammed into a linear two hour runtime simply can’t result in a flawless translation; the two mediums are far too different from each other to cooperate unscathed.

The 2017 Netflix revival of “Unfortunate Events,” on the other hand, fixes this issue. Dedicating two hour-length episodes to covering each of the first four individual books in the series allows the series to create a more believable, intricate setting while providing the characters and story enough time to properly develop at a pace comparable to the source material. The series doesn’t feel cluttered and confused like its ancestor did thirteen years ago, it doesn’t resemble the disjointed story with no conceivable conclusion in sight that the movie was. Instead, it’s cohesive and clear. With the exception of several foreshadowing cues for enhanced storytelling finesse, the series feels precisely how one would expect when desiring to witness the books visually unfold nearly unabridged. It fixes the downfalls of its cinematic cousin by providing a more suitable conduit for adapting the cult classic, thirteen-volume story, nailing not just the tone, but the story, characters and setting in addition.

If films are the standalone novels of Hollywood, television shows are the multi-volume expansive epics that keep readers up late into the night, frantically flipping page after page to see what happens next similar to how viewers click the “next episode” button to gain closure on particularly pressing cliffhangers. The success of “Game of Thrones” and “Unfortunate Events” proves that television, not movies, should be the go-to medium for filmmakers seeking a method to effectively craft a proper, thorough literary adaptation of stories too massive for the cinema.

While the proper production team is still necessary for achieving such a successful adaptation, shifting the enigmatic story and universe of “The Dark Tower” to TV instills greater optimism that the series can overcome its humbling cinematic debut to create a proper translation and bring the acclaimed series to a wider audience. In short, there’s no need to panic just yet.