It’s no secret that this country is in turmoil. The recent and continued waves of protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd have swept the United States with vigor, showcasing the range of complex emotions felt by citizens and activists alike. Expressions of rage, solidarity, fear and hope have abounded, and nowhere was this more evident than at the Queer Liberation March for Black Lives and Against Police Brutality in New York City.

Though Pride 2020 was largely virtual due to COVID-19 restrictions, this single event — a simultaneous march, protest and parade — encapsulated the joy and hopefulness that accompanies Pride while maintaining a sense of gravity, anger toward injustice and most importantly, the desire to continue fighting for the rights of Black, trans and queer bodies across America.

The queer Liberation March on June 28 seemed to “bring back” a type of political stewardship that many queer and trans activists felt had been missing from Pride years earlier. Yet it is in Pride’s history that LGBTQ+ folks have found that sense of urgency again. Before the grand spectacle of colorful Pride parades that characterized the 2010s, there was Stonewall.

The History of Pride

In the early morning of June 28, 1969, eight New York City police officers raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in NYC. This raid was neither abnormal for the time, nor was the particular New York Police Department division that led it. The now defunct public morals division was required to enforce laws relating to “vice and gambling,” including prostitution, gambling, drug use and homosexuality.

The attack sparked a six-day series of spontaneous riots nearby. The Stonewall Riots are largely credited as catalyzing the gay rights movement in the United States and have collectively served as the blueprint for subsequent Pride month festivities, protests and parades.

Like the Stonewall Riots, the spontaneous expressions of unrest that have characterized both protests against racial injustice and the Queer Liberation March of NYC coincide with times of extreme turbulence in the United States. Pride, however, has always harbored a special and specific duality.

Pride marches embody both political urgency and festive celebration, both promoting acceptance for the LGBTQ+ community and advocating for further work to be done. As Pride becomes more popular, the queer community becomes more visible — and thus, the sociopolitical stakes of equality are raised.

In recent years, however, LGBTQ+ critics of pride have become more vocal. The community has experienced much unrest, largely boiling down to a sentiment against “selling out.” The “gay liberation and freedom” rhetoric of Stonewall has given way to more palatable sentiments of identity-based pride, acceptance and harmony. And while the LGBTQ+ community deserves a sense of peace, there’s an aspect of commercialization and deradicalization that has led many activists of late to call for a reclamation of Pride itself.

The Commercialization of Mainstream Festivities

Pride parades are often spectacles of the wildest proportions. There’s triumph in taking up public space, particularly for groups whose rights to outward joy are constantly contested. Aesthetics play as big a role as slogans, and politics play out both on the streets and on the bodies of those who express themselves wholly (and with flare). The pageantry, however, seems to have come at a cost.

Since around 2015, the same year as the landmark Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court decision on gay marriage, summertime Pride parades have been characterized by motorized floats, sponsored by big corporations looking to cash in on “activist capitalism.” Pride sponsors such as Verizon, FedEx and AT&T brand booths and free swag at parades, only to turn around and donate to conservative politicians and threaten protections for LGBTQ+ communities. Police forces block off streets, embodying the “legitimization” of mainstream Pride as a movement about acceptance rather than resistance.

Mainstream Pride, as it were, has faced its own form of backlash. Radical sub-sections of the LGBTQ+ movement have denounced the capitalist, police-attended Pride festivities, asserting both their alterity and the need to fight for members of the LGBTQ+ community who have yet to enjoy the same rights as whiter, wealthier members. In Washington D.C. in 2017, protestors blocked the path of the “mainstream” Pride parade — both rerouting the physical march and the thesis of Pride itself.

Celebrating in 2020

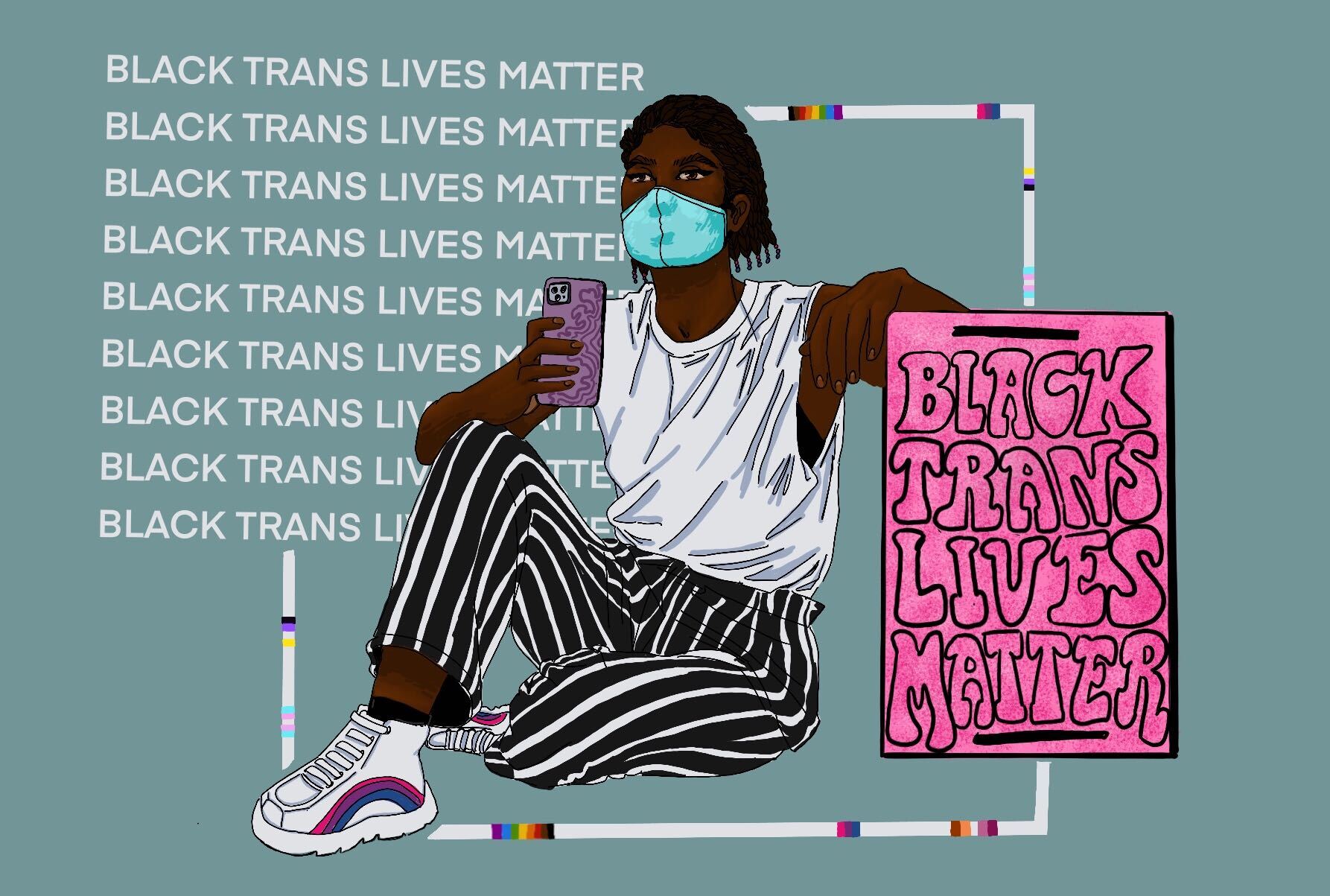

In a year with so few in-person Pride events, however, there was no room for contestation. As Black Lives Matter protests swept the country just days before the kickoff of Pride month, the LGBTQ+ liberation movement found common ground in the fight to end police brutality. The Queer Liberation March in NYC explicitly built off of the Black Lives Matter protests of the previous month, and devoted special attention to Black trans lives.

The Human Rights campaign recently reported that “2020 has already seen at least 21 transgender or gender non-conforming people fatally shot or killed by other violent means. We say at least because too often these stories go unreported — or misreported.” Following the horrific murders of two Black trans women, 27-year-old Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells and 25-year-old Riah Milton, violence against Black communities — particularly, the Black trans women who make up their most vulnerable cohort — activated a renewed sense of political urgency for Pride organizers.

Police brutality also served as a catalyst for a tougher, more publicly radical Pride this year. A large effigy on display at the Queer Liberation March highlighted the role of police misconduct in the death of Marsha P. Johnson, a transgender Black woman who is credited with throwing the “first brick” at Stonewall. Posters and slogans adorned with “ACAB” and the words “police brutality, sashay away” made it clear: Cops are no longer welcome at Pride.

The same goes for corporations, the most prominent of which have been denounced by LGBTQ+ activists for their fiscal contributions to conservative PACs, lobbying groups and candidates. Rather than branded and commercialized floats and parties, the Queer Liberation March in 2020 featured booths offering free community-cooked food, radical literature and of course, lots and lots of glitter.

The Future of Pride

At the conclusion of the march, LGBTQ+ community members and outspoken activists shared their feelings of revitalization as a result of the shift in the culture of this year’s Pride. But what happens next year, when the rage is less surface-level and the post-pandemic world allows for throngs of partygoers to dance in the streets again?

Pride deserves to be celebratory and festive, but like many, I believe the era of commercialized Pride is over. The LGBTQ+ liberation movement has found a new moral rudder in centering the conversation around Black trans women. This direction will propel queer freedom activism forward.

Defending the lives of the most targeted members of society requires attacking structural inequalities at the intersection of race, sex, sexual orientation and gender expression. These big questions deserve a type of activism worthy of answering them, one that meshes the best aspects of the triumph and spectacle of Pride with the continued struggle for LGBTQ+ acceptance, liberation and self-actualization.