Social media has an overwhelming tendency to focus on the negative and attack people for frivolous reasons. Social media minions derive an incredible amount of joy from inflicting suffering upon people, especially celebrities, filtering out every detail of their lives and exposing their imperfections, investigating and poking fun at people to the extremes. Their flaws are highlighted, recirculated and turned into tabloid fodder or internet memes.

The toxic internet web culture often encourages the bullying, degrading and demeaning of women. It most specifically targets women who are guilty of the internet-crime of getting plastic surgery. For them, it launches a hate train, a bandwagon. It conceives of the women as lacking, defective in some way, which consequently breeds nastiness and encourages intense trolling. Ultimately, it seeks to maim and humiliate beautiful women. Being pretty hurts.

The culture seeks to reveal, expose and unveil women, particularly women it deems plastic or artificially beautiful. It searches for holes and reaps benefits from exposure, the high produced from revealing that people have used Facetune (gasp) or Photoshop to edit their pictures, examining them at every angle, studying the size of their lips, the proportions of their face, the roundness of their nose, chin and cheeks. Articulating women as unnatural, fake, posers. Ingenuine models, insta-girls. Cheap. Essentially, the culture lives to perfect the imperfect, express what is ugly about a woman — her nose, her wrinkles. It seeks to crush her self-confidence and make her reliant upon other people’s remarks about her beauty; it makes her judge the voices of others as a reliable indicator of her worth, her beauty, her prestige.

It makes suggestions about what she can improve on, how she can beautify herself, encourages her to finetune herself, get Botox, get cheek filler or butt implants. At times, the culture deifies her. At the same time, it crucifies her for doing so. It vilifies her. It claims she is unbeautiful for daring to be pretty or prettier. It maligns her. It holds her in contempt.

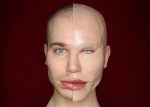

Oftentimes, it defies her; it says the natural laws of beauty make her existence disarming and phony. It contests every person who declares her a beauty and not a beast, claiming her beauty is unfair — she cheated her way to perfection. It decides it will not only judge her beauty, but it will be the only judge. It circulates images of her before she fixed herself, images of her before surgery. It claims her surgical procedures give her an unfair advantage over “natural” women, gorgeous women without plastic surgery, women who didn’t need it to be stunning.

Moreover, it says women who get plastic surgery don’t have a wow-factor. A “plastic” woman is someone unworthy of being loved, is somehow a “bad” woman, is somehow deserving of punishment and rebuke. A woman who ought to be disposed of. Terrorized. Belittled. Demolished.

This culture weaponizes her beauty and her insecurities. It decides a “plastic” woman is an unnatural woman, a woman guilty of some impossible crime, guilty of offending the culture that demands her abasement and mortification — a culture that demands that she give up her status; a culture that says she is no It-girl, no beauty queen, no Disney princess, no role model.

This culture says this woman is deficient of worth, unworthy of self-pride or the pride and fanfare of worshipping others — fans, admirers, people who adore her — people who would exalt her as the mantle of beauty — the (delta of) Venus, the Aphrodite, the Madonna — because her plastic surgery made her beautiful.

This culture demands her sacrifice; it demands that she sacrifice herself. It throws her to the wolves, links her to an impossible standard, demands that she maintain her beauty or forfeit it. It elevates and demotes her for being plastic, makes it her staple identifying trace, her beauty marker. It preoccupies itself with her stardom, in comparison to her lackluster beginnings; it overcompensates by endlessly comparing her “old face” to her “new face.” It seeks always to intimidate, terrify, embarrass, rupture and humble her. It demands that she prove herself.

The people of this culture engage with her by hate-watching her, and this hate-obsessing over her is a form of gatekeeping, a form of regulating her body as if it were the law, indiscriminately searching for proof of misconduct, change or violation with no charge, without a burden of proof or discriminate, overwhelming evidence. This culture scrutinizes; its members participate in her objectification and dehumanization by relentlessly searching for pores, searching for visible differences from the last time she was photographed in public, making comparisons to baby photos and past printed stills, candids, magazine covers or photoshoots, polaroids, family albums, paparazzi shots or photo-ops, meticulously searching for anomalies, proof of plastic surgery.

The culture thrives on cutting people down, reducing them to smithereens — particles of the past, shattered fragments — breaking down their sense of self. At its core, it revels in being nasty to people, assigning value to them or devaluing them based on their appearances, examining every inch of their skin, poring over their bodies, searching for fuel to feed their venom.

The culture loves to critique, but worse, it revels in it. In body-shaming, it seeks to demolish women. Render them glass shards, broken pieces. Sever the link between themselves. People sit behind their screens and pore over the details of women they can’t reach. Women they’ll never be. Women they’ll never get. Women they’ll never keep. Women who’d never give them the time of day (entertain them) in the first place. These women are unreachable, untouchable, impossible to be consumed. Forever separate and estranged from them.

Perhaps that is why these people’s intense fixation with these women turns into obsession and hatred — obsessive hatred — and bleeds into their morbidly intense fascination with humbling women, breaking down women’s psyches, evaluating their worthiness, ripping them into shreds. Destructively tearing into them and pretending their comments are aimed with the intent to give constructive criticism. Tracking women’s bodies and multiplying their irregularities as a guise for surveilling them, expressing concern for their appearance and citing an irregularity as proof of surgery, proof of disappearance, proof of suspicion, proof of probable cause to warrant their investigation, proof of criminality.

All under the watchful eye of a concerned fan, the culture engages in dissection — as if women’s bodies were a scalpel or surgeon knife — cutting into them, studying the anatomy of a woman, analyzing them as if they were public property, gazing at them, poking and prodding them, naming them as cause for investigation, all as if women’s bodies are being legislated, laid out on the stand, the “concerned” fan acting as a witness or prosecutor, and them, the poor, dissected women, forced to act as a defense attorney or a defendant on the stand.

The culture is invested in tormenting women, performing their autopsies and vivisection. It’s obsessed with making women prove themselves valid, making them fight for a legitimate existence free of vitriol and public surveillance, as if women weren’t already tortured enough. As if women weren’t already under the male gaze, as if women weren’t already crushed by their fellow women. As if women were a construction project undergoing demoliton, a crash site, murder victims, the scene of a crime. As if women weren’t already devastated by public opinion and under court-martial. As if women weren’t already punished, as if their bodies weren’t already legislated. As if women need more reasons to defend themselves against the patriarchy and internalized misogyny, sexism and oppression.

Public scrutiny demands relentless preoccupation with women’s body parts, their faces, their noses, their abs, their butts, their cheeks, their lips. People wonder, “Did they get a fat transfer? Did they get a lip injection? Did they get Botox? Did they get lip or cheek fillers?”

Women get told they’re nothing but plastic and because they’re full of it, they could drown in the ocean. Quite literally, when they express concerns, they get told: “There’s enough plastic in the ocean.” Women get ridiculed. They are asked, “What face are you on, face #5, or so? I preferred your second face — that face was immaculate.”

They get called botched. Of their bodies, it is said: “Your ass is full of cement and your breasts are full of silicone.” People endlessly speculate about whether or not a woman has gotten more work done; they make assumptions about her body and even her appearance in the media — they hypothesize about a female celebrity’s temporary disappearance from social media platforms and are curious about the possibility of her forgoing her absence from social media — or her silence. They discuss the merits of her long-term abandonment from fan interaction.

A social media break is never just a social media break. They say, “Her butt implants must have popped,” or “She disappeared to go get a BBL (Brazilian Butt Lift),” or assume, “She just had lipo (liposuction) done.” They make numerous comments about her facial alterations: “She’s on her fourth round of Botox, her face is fresh but she needs to go easy on the Botox and wait for her new nose to set. What, is she on her second nose job now? The bridge of her nose is still crooked, she should have called ______ (insert another female celebrity)’s surgeon, he did a much better job. Now, she looks like Barbra Streisand.” They are never satisfied, tired of critiquing. They say, “Her tits are saggy, she needs a breast lift.” It doesn’t escape my attention that a bad boob job evokes more sympathy from them — the social media trolls and naysayers — than a dream nose job; that would make them envious.

The audacity! How dare a woman get plastic surgery and look better than her regular woman? Apparently, women are supposed to stay miserable and unhappy with themselves, even when they have the means or wherewithal to fix it.

Trolls want women to stay insecure, want them to be the butt of the joke, want them to be uglier than them, that’s why they have more compassion, although pseudo well-meaning, for women they consider botched; women who plastic surgery failed to make beautiful. This is their ideal woman, the rootable icon or role model. Women who are improved by surgery — women who plastic surgery made beautiful or beautiful-er (more beautiful) — are despised and reviled. But there is one exception to this rule: Women who got plastic surgery but were considered naturally beautiful before getting it are exempt from the brunt — the worst, most vicious — of the plastic-shaming.

There is something about the trait of being viewed as naturally beautiful that shelters one like a blanket, that acts as an umbrella against hatred. People are more inclined to bully women that they feel were naturally ugly or otherwise never had a chance of being seen as conventionally beautiful until a plastic surgeon, like a fairy godmother, made them beautiful. They loathe them. They chasten and abuse them, because they can. These women offend their honor and pride somehow, chagrin them.

These women are a threat to them, a picture of how these angry internet people could have looked had they the money, power, connections and ability to change their physical appearance as they see fit, as these rich celebrities were able to. These celebrity women symbolize to them everything they wanted but could not attain within themselves; this is where their intense anger and hostility toward them draws and derives from. These women, to them, represent the impossibility of a dream, a yearning unfulfilled. When they look at them, they are reminded of this stubborn, unyielding fact, and the rage sweeps in, a misdirected, displaced anger that is then projected onto the female celebrity that is most attractive, desirable and heralded as pretty.

To the woman who feels unpretty, this is everything. This is an unforgivable offense. An unbearable fact to contend with. This woman symbolizes unreality — her beauty quite literally seems unreal, partly because it is — and to the woman who looks real but feels unpretty, this is most devastating to live with: the knowledge of her unprettiness. This is what makes her claws sharpen, what makes her spew internet poison.

The power of her hate increases the more the celebrity woman’s beauty increases or the more others view the celebrity woman pretty or desirable. It flattens something inside the envious person who is jealous of the other woman’s beauty. She thinks, “How dare she?” How dare they praise an unnaturally beautiful woman, rave about her divine beauty, while a woman like me goes unnoticed? Aren’t I a divine woman, too? Am I undivine because I’m not rich enough to fix the ugly in me?

She begins to think of herself as ugly because she cannot match the female celebrity’s — the idol’s — beauty. She can’t compete. She doesn’t compare, she doesn’t even fit in the picture, nobody is checking for her. Waiting to prize her, lavish praise on her, deify her. She’s not on the cover of any magazines; she doesn’t top the list of the world’s most beautiful women.

She is an anomaly. A reject. A nobody. And this pisses her off — the fact that she is no one, no one significant in pop culture; meanwhile, the woman who has the power to change her appearance, unlike her, becomes the staple, the icon, the idol. The standard. The it-girl. The X-factor. It enrages her — the fact that the media acclaims the other woman so much. The fact that they worship her. They elevate and esteem her. Little girls want to be like her. Hell, so do adult women. And because it dulls something in her — the envy — her maliciousness sharpens. Her bitterness increases, but so does her audience — the crew of people chiming in, expressing support for her contention that this beautiful celebrity woman is an imposter because she had plastic surgery.

The more reception she gets, the more her boldness grows, until she sets out to make this untouchable celebrity miserable. She preaches to the choir: This beautiful woman is make-believe, is an ugly woman in disguise. A hag, a witch. This she-witch was once an ugly woman like me, like all of us. She’s bewitched people but she was once a nobody, too. Beauty is a magician, and so is a surgeon; the praise of her beauty belongs only to her plastic surgeon, not to her.

This is how the unhappy, feeling-ugly woman turns literally ugly (in spirit), becomes a hater of her fellow woman, becomes a troll obsessed with humbling the beautiful — but surgically-made beautiful — woman. This is why internet culture, while rabid, is toxic: It’s obsessed with humbling women who get plastic surgery to no limit. It’s obsessed with saying a beautiful woman is only majestic if her beauty is natural. It’s obsessed with trying to take away women’s womanhood and deny women personhood if they’ve gotten plastic surgery. It’s obsessed with defiling every part of their being and making them feel guilty for wanting to be pretty because pretty is unreachable, unattainable for other, typically not famous, women. For them, (being) pretty is just a dream.

I have an issue with a culture that subjects women to aggressive questioning. I find it problematic that our toxic internet culture rejoices in policing women’s weight, their bodies, their happiness. Why must our culture regulate and hypothesize about women’s bodies? I find it sickening and revolting. Worse, disheartening, the fact that ugliness — cruelty — is such a turn-on to people. The very practice, the despicable behavior, reeks of human entitlement, human failing. I find it impossible to forgive. Others find it impossible not to succumb to. How sad. How pitiful.

Humans feel they have the right to examine other people’s bodies, critique them and investigate them as if they are cadavers or up for public auction. They don’t. (Women’s bodies aren’t up for sale.) But words are splinters, words can destroy. Words can paper off. Words can embed themselves into a person’s skin, shrink their appearance, splice them off, piece by piece. Words can wound; words can rupture. And a culture that is ruthless to women who get plastic surgery knows this, and it uses words to dismantle these women’s confidence, shatter their self-esteem. For this reason, I ask that people refrain from needlessly exploring every caveat of women’s lives and bodies. I ask for a full-stop, an end to the unspeakable cruelty of policing women’s bodily and personal autonomy.

Attacking women for getting plastic surgery is a form of misogyny. Shaming women for being “plastic” is a form of women’s oppression — period. Stop shaming pretty women who get or have gotten plastic surgery. Stop speculating. Stop obsessing. Stop harassing women — period. Stop being ugly humans. Leave women alone. Leave them out of your discourse. Leave them out of your imaginations. What women do with their lives and bodies is none of your business. The Instagram trend (that high fashion culture popularized) of putting red circles around women’s lips and thighs needs to end — immediately. It’s invasive and a gross violation of women’s privacy, respect and dignity.

Women reserve the right to live free of harassment. Internet bullies, fans and the like have no right to investigate claims of plastic surgery or attack women for it. No one is entitled to women’s bodies. Aggressively measuring and policing every part of their being is flat-out childish, worrisome, obsessive and pathological behavior, not to mention, obnoxious. Grow up! Stop using their looks as fuel for your hatred. Stop using their plastic surgery as an arsenal, as machine gunfire, as gasoline. Stop firing words as bullets, attempting to cripple people’s dignity, sacrifice their joy and happiness. Stop being mean.

And to the women who the culture calls plastic, I have this to say: Getting plastic surgery doesn’t make you a bad person. It doesn’t make you unworthy of being treated like a decent human being. It doesn’t make you revolting. It doesn’t warrant other people’s bullying. You need no justification and owe no one an explanation for getting plastic surgery; you have nothing to atone for, nothing to apologize for. Nobody reserves the right to demand that you tell the world about your procedures. You shouldn’t have to disclose them or have your secrets, your business, your private life publicly revealed. Nobody deserves the right to be cruel to you. The right to deface you. You deserve to live free of stigma and harassment. You are precious.

Pretty hurts. This is why the culture needs to stop shaming pretty women who get or have gotten plastic surgery.