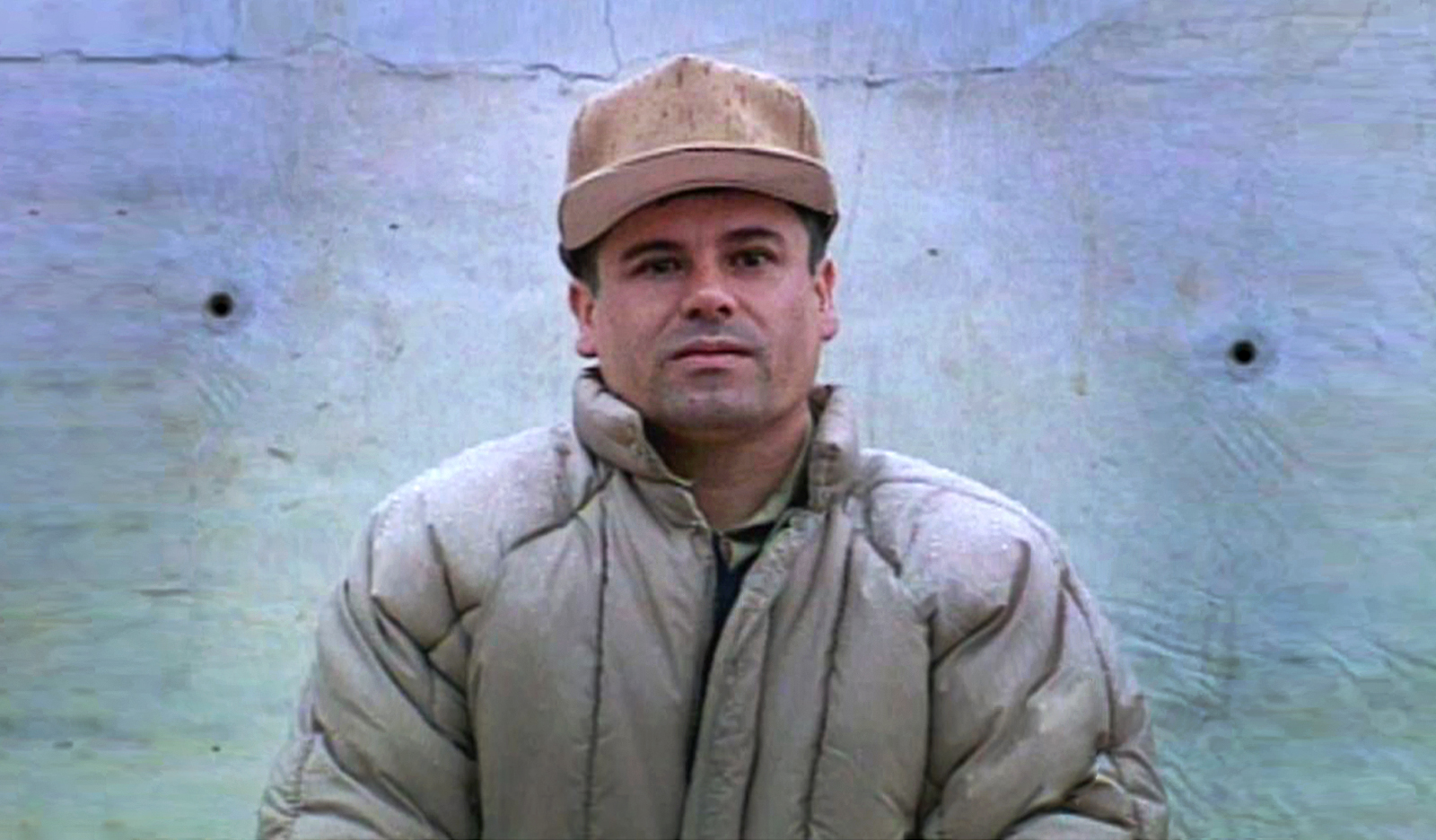

The reported life of Joaquin Guzman, commonly known as El Chapo, is the stuff of legend. Nearly every detail that leaks out about Guzman’s life and his seemingly unstoppable reign as one of history’s most notorious drug lords is mind-bogglingly larger than life.

His cartel dominates the illegal drug market in both Mexico and America, leading to billions of dollars in yearly earnings, a place on Forbes’ list of The World’s Most Powerful People and the title of “most powerful drug trafficker in the world” bestowed on him by the U.S. government.

Even the most basic facts about Guzman are warped by his near-mythic status. His reported date of birth oscillates between April 4, 1957 and December 25, 1954. It should come as no shock, then, that El Chapo has attracted the kind of public fascination usually reserved for dead rock stars, athletes and other cult figures.

Guzman’s road to notoriety deviates from those that typically inspire this immense level of devotion. In a drug-trafficking trial in February, El Chapo was found guilty of several counts of cocaine and heroin distribution, money laundering and firearm possession. During the trial, Guzman’s former associates testified that he was responsible for hundreds of vicious murders (well-circulated rumors suggest a much higher figure in the thousands), as well as regularly raping underage girls.

By all accounts, the moral objections to idolizing El Chapo should be clear. Still, the multiple reports of his ruthless crimes and generally heartless behavior has not stopped him from accumulating legions of fans rooting for him and his escape from the law, as if he were a beloved playoff team cut right before the championship game.

Nowhere can this support be seen more clearly than in his home town of Culiacan, Mexico. After Guzman’s arrest in 2014, a march through the city calling for El Chapo’s release attracted thousands of people. A similar march occurred a year later, though this time the people gathered in celebration, as he had managed to escape

In Sinaloa — the Mexican state Guzman is from and would eventually name his cartel after — El Chapo is viewed as a modern-day Robin Hood figure, though he is technically a billionaire. Reports out of Culiacan claim that Guzman and other notable members of the Sinaloa Cartel were characteristically generous, often distributing chunks of their wealth to needy citizens or going out to local restaurants and picking up the tabs of everyone who happened to be there. There is also the unavoidable fact that El Chapo and his cartel is essentially its own economic force in the state by creating jobs and bringing in money — lots of it.

Sinaloa residents have also said in the past that the presence of Guzman and his cartel, and their lurid reputation, often prevented more violent rival cartels from entering the state.

Guzman, who grew up poor in Sinaloa before working his way up to a cartel kingpin, may not have become an athlete, scientist, movie star or any of the other occupations usually associated with a hometown hero, but he is still an immense source of pride for its citizens.

With only 33 percent of Mexicans expressing trust in the government as of 2013, it’s not entirely a surprise that its citizens would turn its attentions to El Chapo, a figure who has proven himself as willing to support and protect even when the government would not. El Chapo has even become a popular subject in corridos, narrative ballads that have historically been sung by working classes about revolutionary figures like Pancho Villa.

From a poor Sinaloan boy to a notorious billionaire, Guzman’s underdog story has undeniable appeal in the infamously poverty-stricken Mexico. But the idolization of El Chapo is not limited to within his home country’s borders. Each time Guzman is put on trial, convicted and brought to prison (he has escaped twice), it is not atypical to see social media flood with users from around the world calling for his release. Even those that manage to acknowledge his laundry list of heinous acts can’t help but do so without a glint of admiration for his achievements, as well as the sheer level of crime he’s been able to commit.

“Free El Chapo,” one Twitter user wrote, followed by the crying face emoji. “[A]ll he wanted was some money.”

Free El Chapo 😭 all he wanted was some money

— MIKE GUWOP. (@BucketsNdDimes) February 12, 2019

Despite the outrageous violence and its real implications — cartel violence is reportedly responsible for 150,000 homicides in Mexico — the story of El Chapo is undeniably intriguing. He lives a life of fiction made real. He is a flesh-and-blood Tony Montana. People cannot stop admiring Guzman because his life plays out in ways most people can only imagine: mountains of drugs, sprawling estates and multiple daring escapes from prison.

Of course, there is also the exorbitant amounts of money.

Perhaps El Chapo’s global appeal is as simple as that. As salacious as his story may be, the greatest thing separating you from him is the billions and billions of dollars at play. This seems to be the recent guiding force that decides where the world places its attention. Would Fyre Festival have dominated the cultural conversation in the same way it did if it wasn’t known that its organizers had squandered millions of dollars? Would the story Elizabeth Holmes and her failed company Theranos have been as appalling if she hadn’t ratcheted up its valuation to nine billion dollars?

It’s the inescapable allure of success that draws people in, and there is no doubt that El Chapo is extremely successful. Despite the crimes he is known to have committed, which are jaw-dropping not only in their ruthlessness and volume, but also for how long he’s evaded the law, El Chapo’s story is enthralling because he has lived an impossible life, the kind of life that should only exist in a legend.

As a result of his guilty ruling in his February trial, Guzman will be sent to an American supermax prison in Colorado where he will most likely die, should he not manage to escape.