Some have argued that nature is the original art piece of the world, and in some cases, they wouldn’t be wrong — but if nature is rapidly becoming destroyed, what will the world even have left to call art? The environment has always been a part of art, and now, as climate activists demand the world’s attention, scientists are looking to artists to not only motivate humanity, but analyze what art history can tell us about our current climate crisis.

As the 1850s were drawing to a close, the artist Frederic Edwin Church was navigating off the Canadian coast of Newfoundland in preparation for his next painting. The public’s interest had been captured by the search for the Northwest Passage for much of that decade and Church — America’s best-known landscape painter — was no different. Before returning to his studio in New York with about 100 sketches in tow, he had chartered a schooner to approach the sea ice and spent weeks among the frozen blocks.

Church’s monumental painting “The Icebergs” was presented in an exhibition in New York in 1861, just 12 days after the start of the American Civil War. Its original and more politically-charged name “The North” reflected the time’s views on the Arctic and on ice itself.

It was sublime, untamable. Offering no resistance, the icebergs’ features were brutal and sharp. Similarly, a published book that coincided with the exhibition, written by a friend who traveled with Church, accentuated that point: “After all, how feeble is man in the presence of these Arctic wonders.” Before the painting was exhibited in London two years later, the artist added a broken mast that dominated the center of the scene, a reminder of humanity’s fragility.

“That’s kind of the opposite of what modern paintings of ice are saying,” explained Karl Kusserow, the John Wilmerding curator of American art at the Princeton University Art Museum. “Later pieces of art are about the ice melting because of what we’ve done to it.”

Kusserow is referring to works such as “Ice Watch,” an installation by Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, which placed more than two dozen blocks of ice in London that had already been lost from Greenland’s ice sheet, and left them to thaw for passersby, a reminder of the fragile Arctic. “It’s a kind of a flip-flop,” said Kusserow, “using that same kind of metaphor; this element of ice.”

While one-and-a-half centuries have passed between the two pieces — a blink of an eye for the human species and even less so for the planetary cryosphere — the relationship between humanity has changed drastically. In Church’s time, the greenhouse effect had barely been proposed by scientists such as Eunice Newton Foote and John Tyndall. In 2020, we are certain we are literally melting the planet’s ice.

As the world attempts to comprehend the extent of the climate crisis, calling upon scientists, policy-makers and educators, art historians are finding answers of all sorts, which has led to new questions. Most importantly, they are connecting the dots on how humanity’s relationship with nature has changed, and analyzing the historical and modern societal ideas about climate, including the geographical elements of the planet.

For instance, the comparison of the past extent of glaciers in older paintings with current observations has provided information on how long a glacier was before global warming. Likewise, this has allowed scientists to predict how quickly we might lose ice in the future.

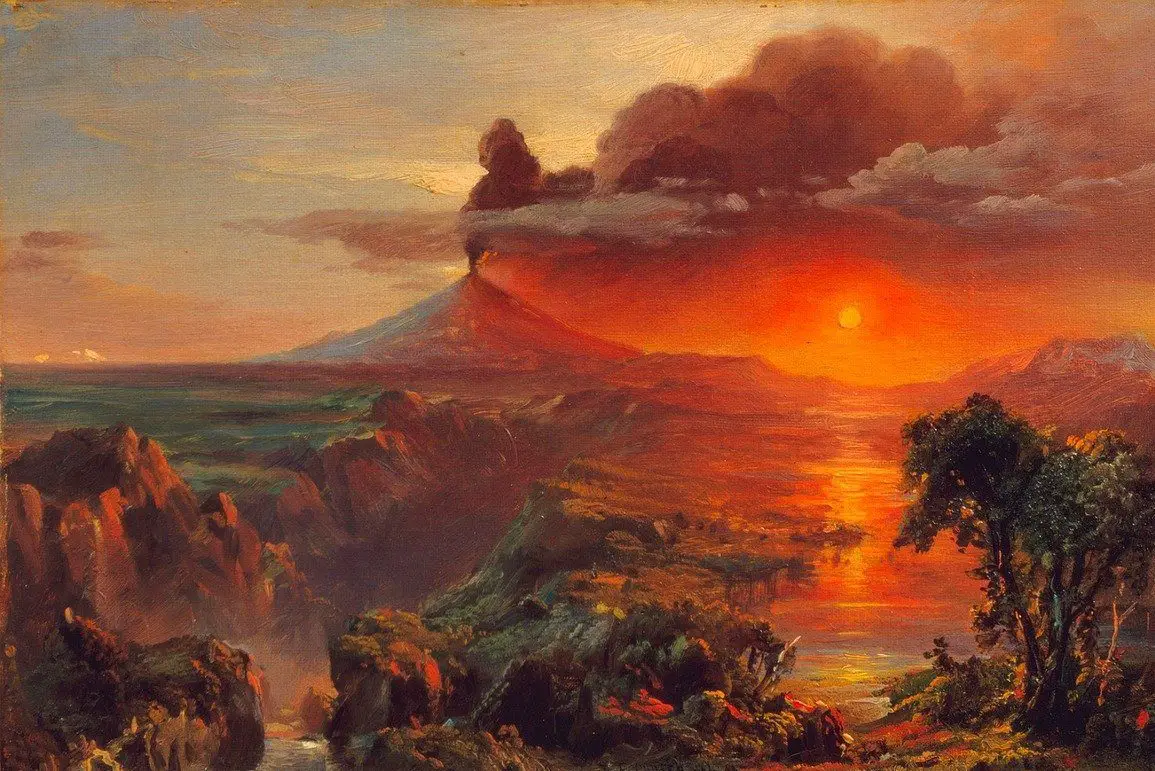

In a similar fashion, scholars from Greece and other countries suggested in a 2014 study that the colors of sunsets painted by famous artists can be used to estimate pollution levels in the Earth’s atmosphere for the past five centuries.

“Nature speaks to the hearts and souls of great artists,” said researcher Christos Zerefos, professor of Atmospheric Physics at the Academy of Athens in Greece. “But we have found that, when colouring sunsets, it is the way their brains perceive greens and reds that contains important environmental information.”

Going farther back in Western European art history, it is evident that prior to the 1500s, there are few depictions of snowy landscapes. However, as the German historian Wolfgang Behringer suggests in his book “A Cultural History of Climate,” the lower-than-usual temperatures during the so-called “Little Ice Age” encouraged European artists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder into a new branch of landscape painting: the winter landscape.

The subgenre includes works such as Bruegel’s “The Hunters in the Snow,” a 1565 oil-on-wood intricate portrayal of an idyllic winter scene. But beyond the snow, it’s the little details that reveal the cultural and social dimensions of how people were living with the idea of changes in their climate.

George Adamson, a historian and geographer at King’s College London, believes that artworks help us understand how past societies dealt with meteorological events. In the 1500s, he says that the depictions of winter landscapes left a bleak impression on the public. Even so, the next time temperatures slightly dropped in Western Europe after the 1700s, a new perception was formed. “When you see snow scenes again in the 19th Century, they tend not to show quite so much hardship. In fact, you get the more romanticised view of the countryside,” said Adamson.

Adamson makes a crucial, nuanced point: the elements seen in a painting don’t make up a climate on their own. These depictions are meteorological conditions, pictures of a time and place. It’s rather the cultural ways in which humans live in those climates, and their representations of them in art, that we should be observing.

Moreover, the best representation of our climate emergency is not in the technical data charts that display the upward concentration of carbon in the atmosphere. The climate crisis is better understood with the climate activism in 2020 through the youth strikers’ signs, the debris left behind after a cyclone and the sketches over wildfire emergency maps. To fully comprehend a climate, even in a painting, we need the cultural artifacts.

“Those elements can probably tell you more about climate than a thermometer does,” said Adamson. Art offers a window into our past, present and future climate that science alone can never offer, precisely because it reflects our frustrations, hopes and anxieties about nature. The question remains: How long will the politicians chip away at the ice? After all, if it’s human behavior that is impacting the glaciers, then it would be better to put down the chisel and accomplish what an argument never will: meaningful, beautiful change.