A few weeks ago I was falling down a rabbit hole of the thousands of YouTube videos that were at my disposal when I came across a Ted Talk discussing one of the oldest pieces of literature. As an avid book lover and a bit of a nerd, my interest was piqued so I hit play and watched as the story unfolded. The video told the story of the first book believed to have been written entitled “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” which follows a king as he searches for immortality. In “The Epic of Gilgamesh” a king of the same name is forced to confront a battle one that he could not return from. Based on prior actions, he is forced to fight a mythical bull that has come to destroy the world. With some help, he defeats the beast and ensures the safety of humanity and his kingdom, then proceeds to reach the ends of the earth in search of eternal life. While the story is interesting in itself, it is not the actual writing that struck me. It was the fact that a text which predated the invention of the wheel was discussing the end of the world.

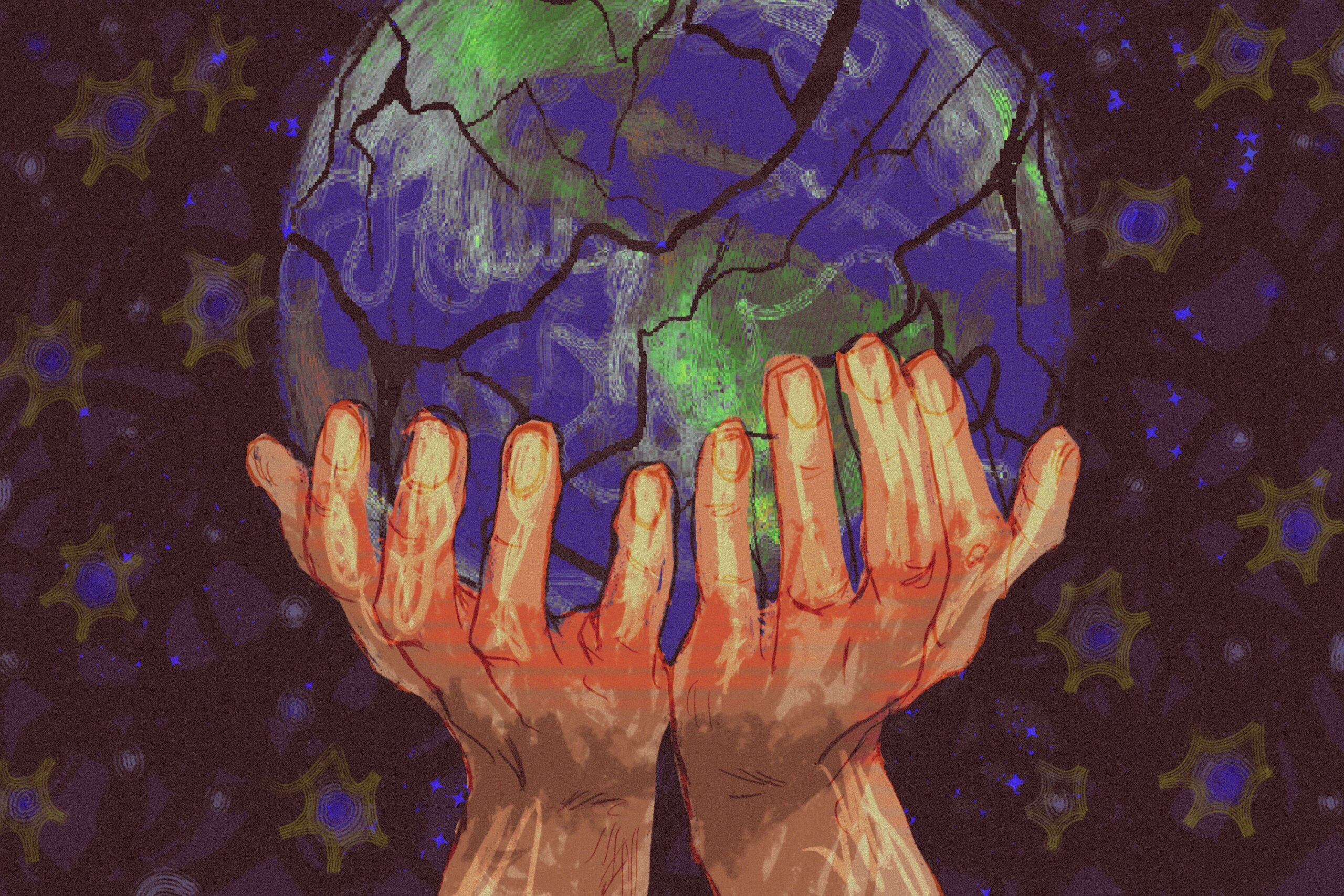

Of course, this shouldn’t have been that surprising as every major religion has a story ascribed to how the apocalypse will unfold. Christianity has revelations, the Nordic traditions have Ragnarök, and Judaism has Armageddon. Each of these stories spells out the end of days in very different ways. Yet whether it all ends through Rapture or Shambhala, hearing “The Epic of Gilgamesh” reminded me of an age-old truth that may be more relevant now than ever. Humanity loves the end of the world.

To clarify, I do not believe humanity loves the end of the world in the truest sense of the word love, as that would be lunacy. Rather, there is an undeniable fascination bordering on obsession regarding the apocalypse that seems to pervade humanity’s psyche unlike anything else. Humanity has been thinking about the end times for as long as we could write. Religion is rife with end-time predictions, and even pop culture seems to share this fixation. With shows like “The Walking Dead” and movies like ‘Leave The World Behind,’ it seems like the end of the world is closer than ever. According to a 2012 poll conducted by Reuters, one in four Americans believe they will witness the end of the world before they pass. Flash forward to 2022, a Pew Research Center study finds that the numbers have actually risen to roughly 39%. While mulling these figures over, having just read “The Epic of Gilgamesh” still fresh in my mind, I only had one question. Why?

It seems reasonable to think that humanity would not want their mind to be ensnared in their demise. In fact, our brains have a mechanism designed to keep these very thoughts at bay. Yet one cannot help but see the near-universal trend of apocalypse preoccupation. The first answer to our proclivity towards the apocalypse lies in our misconstrued notions of it or our romanticization of the end of the world.

Popular culture has painted a pretty interesting picture as to how humanity on this tiny blue dot will die. Whether it be the world goes out with a bang, a whimper, or a zombie apocalypse, it is sure to be at the very least interesting. Even age-old religions paint the end of the world as a time of heroes, villains, with a good story. Our inability to recognize even our own possible deaths and a portrayal of the end as a way to reset humanity has all the makings of a false reality that looks better than our current one. We seem to have this view that the end of the world will bring us back to nature, focus on survival, and end our unnatural love of bureaucracy. Our obsession with the end of the world fulfills a yearning to go back to basics and allows us to fantasize about a world that is much slower than the one we have concocted. Novelist and Harvard Medical School child Psychiatrist Steven Schlozman notes this phenomenon being played out by his students at Harvard. Many of them remarked that “life would be so simple – I’d shoot zombies and wouldn’t have to go to school.” The idealization of the end of the world (a rather unhealthy one) actually humanizes this desire for something different, something new.

I believe that it is in this difference in which we find the deeper reason for our compulsion. Escape. Our lives have a tendency to be filled with tedium. While there are a million little variations in the minutia of our lives, Most of it happens to be filled with terrible monotony waiting for change that would make Estragon and Vladamir decide to stop waiting for Gadot. When we’re not stuck in our mindless routines we find ourselves being fed a narrative of all the evils that pervade our world at an alarming rate. The idea of getting away from all the muck and day-to-day modern living is a fairly common experience. A study published in SWNS Weekly actually found that Americans spend roughly thirteen hours a week participating in escapist behaviors like daydreaming. Daydreaming is ultimately about escaping our present reality like a relationship, financial struggles, or even just boredom. Through daydreams, humans enter a fantasyland where things are better, more exciting, and a respite from our present circumstances. Apocalypse can provide this respite.

While the end of the world is usually thought of as horrifying, it does provide intrigue, mystery, and possible salvation from boredom. If the world ends, you don’t have to go to work. There will most likely be something greater than shuffling papers that you have to do. The End of the World inspires ideas of parts to play that may actually be important in this grand stage we call life. The Apocalypse can be seen as a way to matter, to be more than you already are. While it may seem like a silly fantasy, our collective focus on the end of the world could possibly be an outlet for our unhappiness. It can represent life without the typical strife, where the worst cannot happen because it already has. It is through this final notion, or a world without pain and tedium, that we find out the final reason for our collective love for the apocalypse. This is the end of suffering and an era of bliss.

Once the dust settles and we’ve had our fill of adventure, the end of the world typically implies the end of humanity’s suffering. With our collective yearning for escape comes a deeper desire. Most end-of-the-world stories, once the earth has faded to dust, seem to offer an eternity with an unchanging reign of peace, good-will, and true happiness. In apocalyptic tales like this, there is a halt to the shifting sands that are our lives. There will be no more worrying about maintaining our place, and struggling to survive will be a thing of the past.After our story ends, there is nothing left to happen, to do or to fix. There are no more plot points, and no more lives to live. It just is or it is not. This end of suffering that the apocalypse brings is something that we cannot help but relish in. It is stable, dependent, and cannot be taken away. What may be seen as the world’s greatest change just may be the one we hope will end it for good.

The apocalypse has been the subject of great importance for many eons, and it will most likely stay that way. Our want, need, or whatever you may call it, for the end of the world is something that is ingrained in us, both by the forces that shape us and by who we are as humans. There are no clear cut answers as to why we seem to be so obsessed with our end, but as long as romanticization, boredom, and suffering exist, it can be sure that our minds will still be fixated on our final act. Humanities’ natural tendencies towards these stories shape us into the humans we are today. The end of the world allows us to have a deadline which gives us meaning, brings life into perspective, and ultimately makes everything worth doing. I cannot answer as to why this is, but it seems that for as long as humanity has an end date, this race to the finish, our need to do something grand, to make our mark, will always be.

The end of the world may not be near, but we will think it is for as long as it isn’t. It is just our nature.