In their struggle to fight against the Republican party’s dominance, America’s liberals often view Latinos as a group that can help them prevent conservatives like Ted Cruz, Donald Trump or Rick Scott from taking power. However, the major flaw in the Democratic party’s strategy is that calling Latinos a unified group is a bit of a stretch. What liberals fail to understand as they try to regain control of Congress and eventually of the presidency is that a large portion of Latinos don’t feel threatened by Trump’s rhetoric and might even agree with him.

Throughout his presidency, President Donald Trump has threatened ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), advocated for eliminating the Temporary Protected Status Program for Central American refugees, referred to undocumented Mexican immigrants as rapists and drug dealers and has called for the construction of a border wall. As a result, the White House has developed a tense relationship with liberal Latinos.

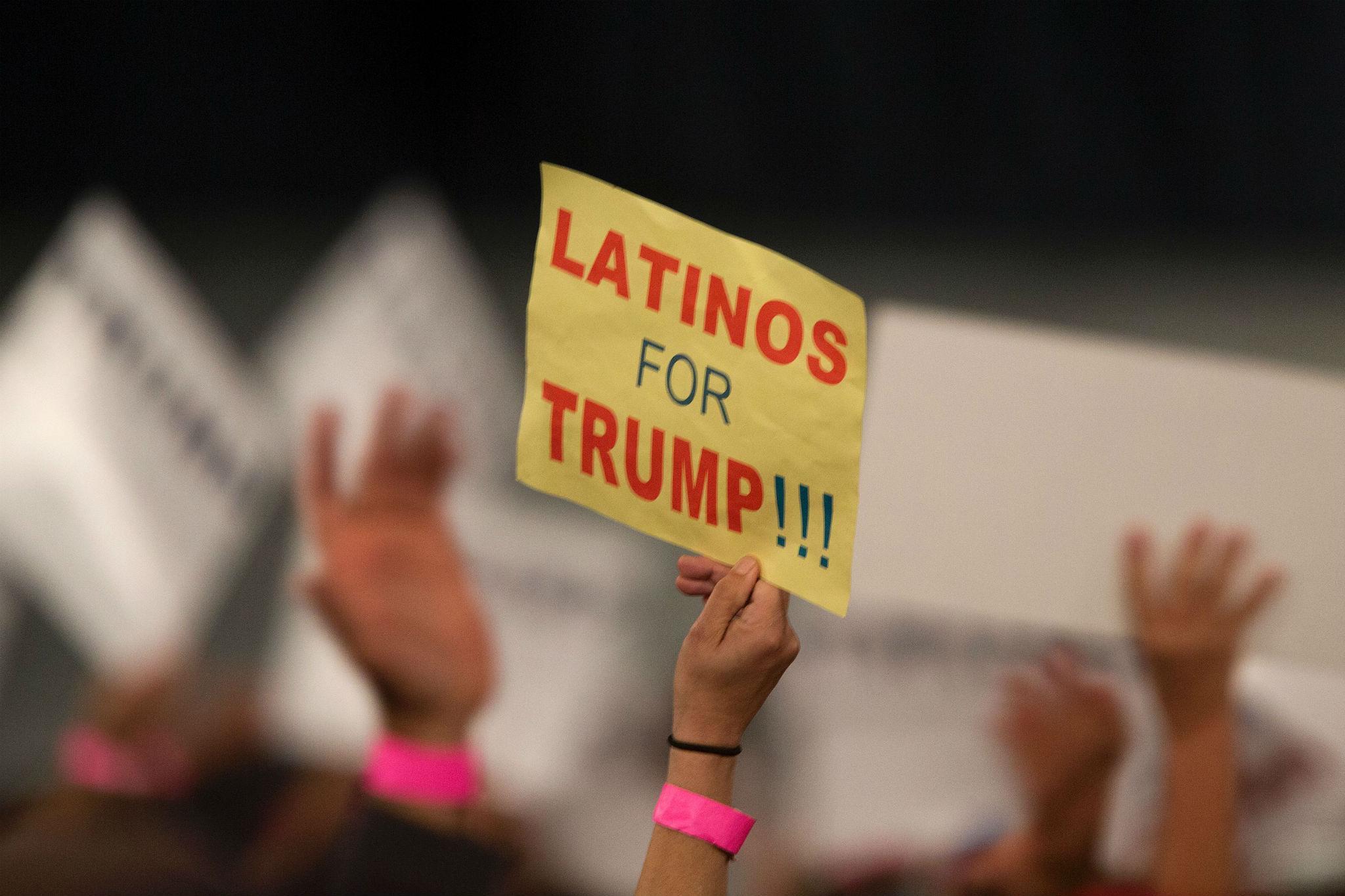

Still, the numbers of Latinos who cast their ballots in favor of Trump’s party shows that not all Latinos are feeling uncomfortable. Rather, they might even paradoxically feel empowered by his nationalist policies.

Who’s Voting?

The Pew Research Institute found that almost 30 percent of Latino voters this November voted for Republican House of Representative candidates, and reported that the Democratic party has been losing favor with Latinos since 2016. Under the Trump Administration, the idea of Latinos flocking to the Republicans appears ludicrous, but a closer look at who are the Latinos in the country’s voting booths can clarify why they seem to be voting for their own demise.

The composition of Latinos living within the U.S. is diverse and cannot be reduced to a monolith, despite the political campaigns that inadvertently do so. Prior to the 1970s, Mexican Americans were the dominant population in the United States, but surges of devastating violence and natural disasters have prompted new ethnic groups of Latinos to head to the U.S.

Waves of immigration throughout the last several decades have led to a transformation of America’s Latino population that politicians have yet to recognize. Beginning in the 1960s after the Cuban Revolution, Cuban Americans have been a major political influence in Florida, especially in the Miami-Dade area. After the civil wars in Central America in the 1970s and 1980s, more Salvadoran, Guatemalan and Nicaraguan immigrants have settled throughout the U.S., particularly in California. Most recently, in 2017, the destruction of Hurricane Maria compelled nearly half a million Puerto Ricans to migrate to the U.S. from the tropical island. Understandably, each wave of immigrants brought with them unique experiences and beliefs that not all Latinos share.

Talking about Latinos as a single body, therefore, isn’t useful to understanding how they vote in America’s elections. Instead, Americans and politicians need to begin to approach each Latino group as an entirely different voting population. Only by doing this will they be able to attract their votes effectively during campaigns and harness their power to vote against hateful politicians.

Mexican Americans’ Disconnect from Central Americans

This summer’s coverage of the family separation and detainment of migrants in the U.S. became a central topic within discussion about Trump’s attitudes toward Latinos. Some hypothesized that the images of incarcerated children would drive Mexican-American voters to rush to the Democratic party out of sheer horror. However, this was not the case this fall. In reality, Trump’s new anti-immigrant policies are not directly affecting third- or fourth-generation Mexican Americans — or even Mexicans nationals, for that matter.

Most Latin-American migrants living in detention and whose crying reverberated through cable news this summer actually come from Central America. Salvadorans, Guatemalans and Hondurans fleeing a combination of state terror and gang violence are the ones who are embarking on a dangerous trek across Mexico to reach the U.S. for asylum.

For Central American immigrants living in the U.S. and voting in the election, the images of the migrants being detained might have influenced how they cast their ballots. However, Mexican Americans whose families have been here for generations might not sympathize as much with the migrants’ plight. Instead, they place their faith in America’s immigration system and condemn anyone who tries to bypass it.

This month for instance, Paul Rodriguez, a Mexican-American comedian, spoke to TMZ about his candid support for the Trump administration’s border policies. “Well, I believe America should protect its borders,” he remarked. He later added, “My parents came in the right way. They stood in line for days.”

While Rodriguez isn’t a representative of all Mexican Americans, his support for Trump’s policies is not an isolated phenomenon. Even as a first-generation Mexican American who has had experience with the immigration system, Rodriguez’s view of Central Americans is also shaped by the xenophobia inherent in Mexican national pride. Recently, on social media, a group of Mexican nationals created a page known as El Movimiento Nacionalista Mexicano, or the Mexican Nationalist Movement. Quoting from neo-Nazi websites like The Daily Stormer and alt-right pages like Breitbart, adherents of the movement have participated in organizing anti-migrant caravan protests. Just as the U.S. sees Central American migrants as foreign threats, so do some Mexican nationalists.

In both Mexico and in the U.S., the myth that all Latinos are united by language or by shared traditions is false. Instead, Latinos see themselves tied as citizens to their country, whether it’s Mexico or the U.S., and are less willing to connect with people that they see as foreigners. By the time Mexican Americans are voting, the thought of detention centers affecting Salvadoran or Honduran families may not even cross their minds as they tap on a Republican candidate’s name.

Cuban Americans’ Whiteness

Still, the political divisions present among Latinos in the U.S. don’t exist only because of Mexican Americans voting straight-ticket for Republicans in Texas or California. Looking to Florida, many second- or third-generation Cuban Americans also fail to empathize with migrants from Central America. Nationalist movements aren’t to blame in this case, however. In 2006, the Pew Research Center found that more than 80 percent of Cuban Americans identify as white, more than any other Latino group in the U.S. Simultaneously, they also voted for Trump at higher numbers in 2016. In general, Cubans are more likely to identify with whiteness than with being a part of a larger Latin-American community.

Nevertheless, Cubans aren’t completely irrational for identifying as white in Trump’s America. Since the 1960s, Cuban immigrants in the U.S. were able to become residents more easily than virtually all other Latin American immigrants entering the country. It’s also important to note that most of these Cuban immigrants were middle- or upper-class Cubans who were fleeing the communist regime that Fidel Castro installed in 1959. As a result, most Cuban-American voters tend to gravitate toward conservative politics that are starkly different from the socialism they left behind in Cuba.

Much like Paul Rodriguez, it’s easy for Cuban Americans today to argue that their parents or grandparents earned the merit of entering the U.S. legally. It’s not surprising that Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz, both of Cuban descent, are perhaps two of the most recognizable faces of the Republican party. Naturally, in 2018, Cuban Americans can’t help but not fully understand the experiences of Central Americans and Mexican immigrants fleeing poverty and violence.

This month, The Miami Herald interviewed Cuban refugees attempting to enter the U.S. about the Central-American migrant caravan and reported that some Cubans don’t believe Central Americans face the same struggles that they do. In the feature, one interviewee said, “They live in free [non-communist] countries. They have the possibility of working and getting ahead. Why should we be treated like them?” Even before entering the arena of American politics, Latinos quickly attempt to disassociate from other groups.

Regardless of any campaign’s efforts, Latinos of different countries, races and classes will most likely disagree on politics — even during the era of Trumpian politics. By placing Central Americans, Cubans and Mexican Americans into a single voting group, they fail to understand the complexity of Latinos’ relationships with one another. Assuming they all believe in the same ideals is not only wrong, but also sets up political parties for future losses in key states like Florida and Texas. Because Latinos are so diverse in the America, leaders need to focus on captivating all sections of American society with their vision for the country’s future in order to win the so-called “Latino vote.”