The Power of the Presidency

How and why the presidency has grown stronger, and why it matters.

By Jonathan Kim, University of Texas at Dallas

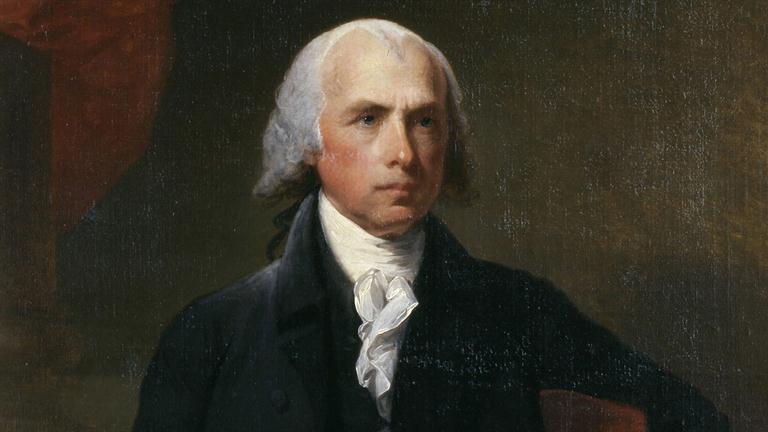

In designing the Constitution, which some have called the “holy writ,” the Founding Fathers had no doubt that man is somewhat Hobbesian by nature; in the Federalist Paper No. 51, James Madison famously wrote, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary…In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

In other words, man, without any legal impositions in governing other men, is unlikely to find qualms in sacrificing the good of others for his own clout.

Madison, as a critical realist, considered this intrinsic lupine quality when he titled his No. 51 paper “The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments”; he believed to be necessary a new dispensation wherein the different branches had no considerable leverage in power over the others. In fact, at the time of the Constitution’s framing, Madison advocated for a bicameral, or split-in-two, legislature because he worried that a unicameral one might prove too powerful.

For reasons not unlike the case for a bicameral Congress, Madison wanted the executive branch to stay unitary, in fear that an internal split might considerably demote its strength. However, even he could not predict the growth trajectory of the executive, which now, over two hundred years since the Constitution’s passing in 1789, has become by far the most quickly growing branch in both size and power, especially in dealing with foreign affairs. (Foreign affairs as a word-duo never appears in the Constitution, and so has largely been involved in the “zone of twilight,” which was coined by Justice Jackson in his famed concurrence in “Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952)” to describe the umbra in cases in which the constitutional authority between Congress and the president is unclear.)

Although the growth in executive power, particularly in foreign affairs, may be most noticeable in the past century, the roots of such power trace back to President Washington, when he declared neutrality in the wars between England and France. Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality had sparked controversy, and a noted debate, in regard to the president’s power to legitimately declare “neutrality.” (Under Article 1, Section 8, Clause 11, the Constitution prescribes only to Congress the power to “declare war,” in which some had also argued includes the power to declare neutrality.)

The debate took the unofficial title of “Pacificus-Helvidius,” in which the two most prominent polemical pugilists at the juncture, Hamilton (Pacificus) and Madison (Helvidius), took the helm at the respective sides of the debate, and thus began the abiding tension between Congress and the presidency.

The roots of executive power have since grown exponentially deeper and stronger with each succeeding president. Early on, President Jefferson asserted his authority as commander-in-chief, whose roles on which the Constitution is notoriously ambiguous, by ordering the Navy out to high seas to defend American merchant ships from being molested by the Barbary pirates.

However, he had sent the navy without first asking permission from Congress, and without Congress having formally declared war, although the happening is called, among other names, the “First Barbary War.” (N.B. The President can only direct, and dispatch during war, the military that Congress solely creates and provides, though this distinction has blurred over time to the executive’s benefit.)

In the classic case cited by later presidents when suspected of over-reaching their legal powers in wartime, President Lincoln suspended habeas corpus, which supplies a prisoner the right to be held only if their detainers demonstrate legal basis for their custody, while claiming the action to be within his jurisdiction. He is literally the only president who has ever suspended habeas corpus, and yet his successors continue to cite his suspension as good reason for any shifty actions that they commit under the guise of “national emergency.”

Presidents have since pushed the boundaries of their authority by citing precedents and exploiting the “zone of twilight” that lies between them and Congress in dealing with foreign affairs. But even Congress has contributed to the steady growth of presidential power.

As Louis Henkin, in his book “Constitutionalism, Democracy, and Foreign Affairs,” points out, “Congress generally acquiesced even in the President’s deployments of forces, and the Senate in his executive agreements. Later, a growing practice of informal consultations between the President and congressional leaders disarmed them as well as members of Congress generally and helped confirm presidential authority to act without formal congressional participation.”

For example, after Kim Il Sung launched a full-scale attack on South Korea in June 1950, President Truman swiftly responded, without first seeking Congress, by sending air and naval support to South Korea. (Senator Tom Connally, when asked whether congressional approval was necessary, told Truman, “If a burglar breaks into your house, you can shoot him without going down to the police station and getting permission.” Remember, the president can only dispatch forces once Congress declares war, which never happened in Truman’s case. Connally’s metaphorical advice was wrong not only from this fact, but also since the metaphor seems to imply an invasion of one’s own homeland, not of a country on the other side of the planet.)

Although Congress never officially declared war on North Korea, it still continued to fund Truman’s missions. Its explicit acquiescence during the Korean War had broadened the president’s power over the military to an unprecedented level.

In fact, America’s involvement in the Vietnam War largely played off the precedent that Truman had set forth during the Korean conflict; Congress never declared war on North Vietnam, but still played along with the president’s tinkering of his military might. But, after both wars, Congress eventually grew too frustrated and passed the War Powers Resolution of 1973, which outlined the contingencies, including a sixty-day limit of military stay on foreign land, by which the President can deploy armed forces. The resolution, at first vetoed by Nixon and then whose veto Congress overruled, was an attempt to check the president’s power from growing too far beyond congressional supervision.

However, the resolution was not enough to hinder Clinton from intervening during the Kosovo War and Obama in Libya; both presidents have been accused of violating the resolution’s sixty-day limit after which troops who are actively stationed on foreign land must withdraw. But their seemingly reckless attitude toward the resolution reflects a two-century-long trend of growing executive power that has been continually substantiated by added precedents.

And so, the “zone of twilight” between Congress and the executive branch when dealing with foreign affairs, the precedential effect leading to increasingly confident presidents, and Congress’ acquiescence to broadly-reaching executive powers have all factored in as to why the executive branch has grown so quickly in power. But, there are a few more important factors to consider, especially while keeping Trump in mind.

In his 2008 paper published in the “Boston University Law Review,” William P. Marshal, law professor at the University of North Carolina, identified eleven plausible reasons for such growth in power. (I highly recommend his paper to my beloved readers.) Though all his listings are relevant to the current political climate, three of them are particularly applicable in forecasting the effects of Trump’s administration. They are: “The Role of Executive Branch Lawyering,” “The Media and the Presidency” and “The Need for Government to Act Quickly.”

The Role of Executive Branch Lawyering

What it means

According to Marshall, because of “justiciability limitations,” many of the questions surrounding “the scope of presidential power, such as war powers, never reach the courts,” and instead are addressed by and circulated within the Department of Justice (DOJ) and its Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), both of which are within the executive branch.

Since the president appoints the Attorney General (AG), who heads the DOJ, he can assure that the views of his AG align with his own, even to the point where the AG sees his primarily duty, in the words of Justice Jackson, as “partisan advocacy.” (President Kennedy appointed his brother, Robert Kennedy, as his Attorney General for reasons not speculative.) As Marshall points out, “This means, in effect, that the executive branch is the final judge of its own authority.”

Why it matters

On February 8, 2016, the Senate confirmed Jeff Sessions as Trump’s Attorney General. Sessions, a junior senator from Alabama, played a large role during Trump’s campaign, but the most virulent accusation against him is his racism.

Back in the 1980s, Sessions was working on a case in which two Ku Klux Klan members, in retribution for the acquittal of a black man who murdered a white cop, slit the throat of another black man and hung his corpse from a tree. When Sessions found out that the Klan members smoked marijuana during their heinous crime, he allegedly said that he thought the KKK was “Okay until I found out that they smoked pot.”

He later claimed his quote as a joke. But what type of person could joke about the murder of an innocent man who had his throat slit by overtly racist men, and expect to perform his duty as a scepter of the law? Our newfound Attorney General is apparently a person of such type.

With his almost decade-long relationship with Trump, his nontrivial role in the campaign and his reputation as a righteous racist, Sessions will now be the “final judge” on the legal issues that rise within the executive branch.

The Media and the Presidency

What it means

It is no mystery that technological improvements have broadened the president’s exposure to the public. Since Jackson, and with the dominance of television, presidents have enjoyed the center stage on national media, thereby propping the image of the president as the “leader” of the country.

Marshall writes, “Because the President is seen as speaking for the nation, the Presidency is imbued with a unique credibility… Additionally, unlike the Congress or the Court, the President is uniquely able to demand the attention of the media and, in that way, can influence the Nation’s political agenda to an extent that no other individual, or institution, can even approximate.”

Why it matters

Trump’s relentless use of Twitter, of which a history has been documented, to repeatedly spit virtual diatribe against the media has given him unprecedented power in influencing public thought.

He most recently suggested that the media was complicit in covering up terrorist attacks around the world; at the U.S. Central Command in Florida, he said, “You’ve seen what happened in Paris, and Nice. All over Europe, it’s happening. It’s gotten to a point where it’s not even being reported. And in many cases the very, very dishonest press doesn’t want to report it. They have their reasons, and you understand that.” (Cilliza from “The Washington Post” wrote on the dangerous implications of the italicized sentence.)

Thus, the culmination of humanity’s technology lies in the hands of a president who compulsively passes blame and rabidly criticizes the aggregate “media,” while hypocritically using those same media outlets to feed his own ego.

The Need for Government to Act Quickly

What it means

During the time of America’s founding, attacks by foreign governments would take weeks, or months, to reach American soil, but now, the imminence of such an attack would last only a few seconds. As Marshall pointed out, “The increased speed of warfare necessarily vests power in the institution that is able to respond the fastest—the presidency, not the Congress.”

Thus, the president has “unparalleled ability to direct the nation’s political agenda,” while Congress, as it traditionally has been, would likely not second-guess, and rather reinforce, the president’s decision in an emergency. Marshall even believes that Congress would be unlikely to confront the President by “cutting off military appropriations.” (One of Congress’ most powerful assets is its control over the nation’s purse.)

Why it matters

“A nuclear war is best avoided.” I’m not sure how much of that statement Trump actually believes.

Some writers have alluded to the Cold War when writing on America’s relationship with China, Russia and North Korea. However, in today’s era, when even North Korea is projected to have an inter-continental ballistic missile (ICBM) by 2020, and with Trump’s likely itching trigger-finger, the threat of nuclear war has become more real and viable than it had during the Cold War.

And perhaps it will be during the height of such tension, or maybe not even, when Trump issues forth a “national emergency,” and will deploy troops in his own cause without much hassle from Congress. And with his propensity for showmanship, and need to compensate for his insecurities with popular control, is it implausible that Trump might one day bring America to the brink of illiberalism and autocracy?

Some say that such a process has already begun. In his piece published by “The Atlantic,” David From wrote a shivering account of what Trump’s America could look like in four years, and warned American citizens to take action now in restraining Trump’s power before it becomes too late.

As I have shown my readers, the powers of the executive branch have grown for various reasons at a rate considerably higher than that of the other two branches. With Trump in the Oval Office, such powers are not likely to recede, but will rather exponentiate.

Without popular protest, the only ones to blame for an eventual autocratic America are its people; as From writes in the coda of his piece, “We are living through the most dangerous challenge to the free government of the United States that anyone alive has encountered. What happens next is up to you and me.”

We need to realize that, though presidential power has traditionally grown, it must never exceed the powers invested to it by the Constitution. We the People of the United States are no angels, but do we not have the duty, as members of a Republic, to govern our government and check its power? If we are not willing to fulfill that duty, we have no right to complain once our iconic democracy molders into a Trumpist autocracy.

Humorous beyond words that Libtards and Cuckservatives now decry “executive branch overreach!” when for 8 years they did shit about it. For the 8 previous they did shit about it. So long as the STATE continued to grow. Now…NOW,it’s a “crisis” because someone got elected who might actually come along and make lazy, worthless, unelected and unaccountable Bureaucrat-fitlh do a real job or GTFO. Many of us have been voting for decades and are sick to death of the false choice given every election cycle while the size, scope and unimaginable power of the leviathan that is the FEDGOD continues to grow, unabated.

MAGA.

Dear Derek Hoffman,

I understand that sentiments are high, especially since Trump’s election and his administration thus far has brought much controversy. From reading your poorly written and thoughtless response, I understand that you are tired of the “Bureaucrat-fitlh,” and I also sense that you are just concerned about the vast disconnect between the “FEDGOD” and the general American people, like you and I. And in that concern, I join you.

Both of us have a passion for our beloved country, though we may have different views towards our current leader in office. I hope that we will find a way for our joint passion to spark civil dialogue and respectful exchange; only then can we hope to help change our country for the better.

I will give you the benefit of the doubt that you had written the response with the expectation that it would not be published, and that you had written it to let off some steam. And so, if you wish to correspond further, you can contact me through my personal email: jonathankim228@yahoo.com. In consideration of my other readers, I believe that a private conversation going forward is most fitting.

Wishing you the best,

Sincerely,

Jonathan Kim

Dear beloved reader,

As I’ve noticed that this article is trending, I thought it might be helpful to proffer you two more articles that other, and more suited, authors have recently written (both on Feb. 7, 2017) regarding Trump and the increasing powers of the presidency. Since replies don’t allow hyperlinks, I will include the links at the bottom of this letter.

In his New Yorker piece, Ryan Lizza mentioned, from a response he received from Jack Goldsmith, a former Justice Dept. official in the W. Bush administration, how Trump, “in the extreme scenario,” might ask Congress to suspend habeas corpus.

In his NY Times op-ed piece, John Yoo, a lawyer for the Bush administration who was also an ardent defender of extreme post-9/11 policies, wrote on how a constitutionally-illiterate Trump is trying to expand executive power.

Going forward, I encourage you to stay vigilant on Trump’s attempts to upend our country’s tradition of checked governmental power and, most importantly, the principles, values and authority set forth by our Constitution.

The Constitution is, and always has been, the supreme law of the land. Once Trump’s words and actions violate the Constitution, he will become the supreme law of the land. That is the definition of an autocracy.

And without our immediate and forceful backlash to such outright violation, we will be tacitly approving the demolition of the history and principles on which our country stands, and on which it had always stood.

I implore you to read and study the Constitution and America’s history. Only then will you be able to understand the danger of the time in which you now live, and be able to do something about it.

As always, I wish you the best.

Sincerely,

Jonathan Kim

Ryan Lizza, New Yorker: http://bit.ly/2kDELnF

John Yoo, NYT: http://nyti.ms/2kEolOm

[…] Source: Donald Trump and the Rise of the Executive Branch […]